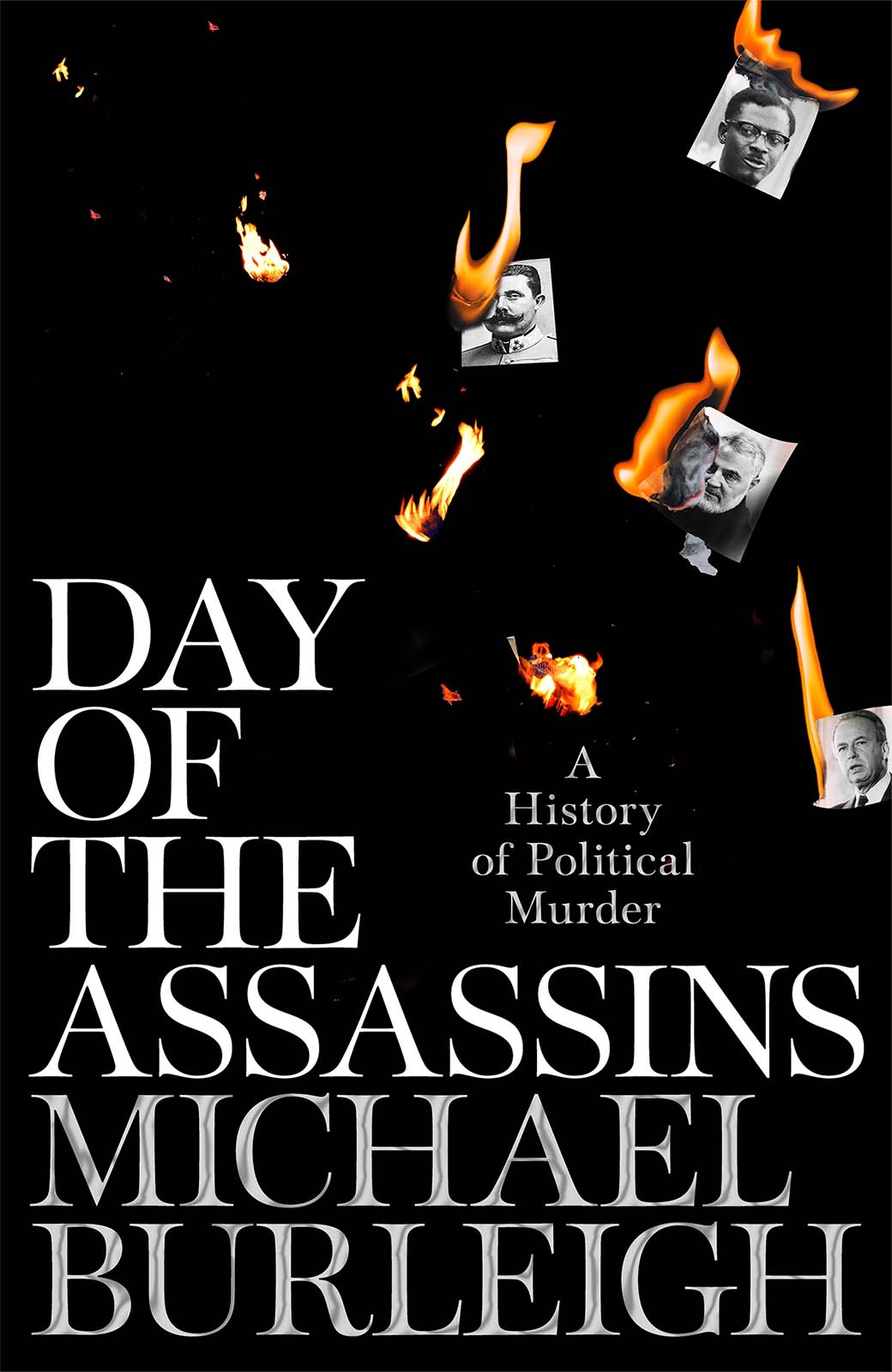

MICHAEL BURLEIGH

DAY OF THE ASSASSINS

A History of Political Murder

Contents

Second Murderer: I am one, my Liege,

Whom the vile blows and buffets of the world

Hath so incensd, that I am reckless what

I do, to spite the world

Shakespeare, Macbeth 3:1

The important thing to know about an assassination or an attempted assassination is not who fired the shot, but who paid for the bullet

Eric Ambler, The Mask of Dimitrios (1939)

He wanted to carry himself with a clear sense of role, make a move one time that was not disappointed... He thought the only end to isolation was to reach the point where he was no longer separated from the true struggles that went on around him. The name we give this point is history

Don DeLillo, Libra (1988)

Prologue

Let us go on a journey, beginning with James Bond. The British Secret Intelligence Service (also known as MI6) are the best in the world at state assassinations Bond, after all, has a licence to kill. British assassins are in high demand, in fiction at least. In Frederick Forsyths 1971 thriller The Day of the Jackal, when French right-wing fanatics could not kill President Charles de Gaulle in 1962, they hired an expert rifle shot from Londons Mayfair.

The classically educated elite are familiar with the murder of Julius Caesar, but know less about the Middle Ages and Renaissance, when ancient ideas on tyrannicide were expanded to permit inter-confessional killing of heretics. A few might recall that nineteenth-century democratic leaders were assassinated: British Prime Minister Spencer Perceval in May 1812 and American President William McKinley in September 1901 plus a few Russian tsars. Next we come to the most consequential assassination of all time: the shooting of Archduke Franz Ferdinand in Sarajevo on 28 June 1914, a single event which handily simplifies the more impersonal causes of the First World War.

The Nazis assassinated many people, including former Chancellor Kurt von Schleicher and Austrian Chancellor Engelbert Dollfuss both in 1934, as one might expect from mass-murderers. No one knows much about Italian Fascists, let alone what the Soviet NKVD did far beyond Russia. But the Allies were also responsible for killings, as in wartime enemy commanders became legitimate targets. The icy SS General Reinhard Heydrich was killed by Czech SOE agents in Prague in 1942, while the Americans hit the Japanese Admiral Isoroku Yamamoto in Operation Vengeance, when his plane was ambushed over the Solomon Islands in 1943. We can next move onto the murders committed by the CIA and KGB, a kind of warm-up for the assassination of John F. Kennedy, Martin Luther King and Robert Kennedy.

The assassinations of Anwar Sadat and Yitzhak Rabin in the Middle East damaged the ArabIsraeli Peace Process. Russia seems to kill critics and opponents with apparent impunity though we should connect this to a lineage that stretches back to the NKVD and KGB, this might detract from the focus on President Putin. We cannot avoid the gruesome murder of the Saudi journalist Jamal Khashoggi in Istanbul, but what can we do with the killings of Daphne Caruana Galizia in Malta or Walter Lbcke in Kassel, other than to say that they were random? In fact, how do we make sense of assassination at all?

Like most people, I do not like being told I am going on a journey whenever I watch a TV history documentary. Lets dispense with this version of assassination and see how it might be done more analytically, while allowing due space for events which are both random and inexplicable.

Nowadays, the James Bond films are little more than exotic travel adverts and opportunities for product placement. The twenty-five films in the franchise are filler for TV schedulers. The British Secret Service do not assassinate people and do not recruit would-be Bonds, and their sophisticated chiefs would be horrified if some out-of-control British politician asked them to do so.

The thirty-three attempts to kill President de Gaulle by the Organisation Arme Secrte did not actually include any foreign gunmen they had French Legionnaires and paratroopers to do the business. The French DGSE (Frances MI6) still maintains a training school for assassins, as an ongoing investigation has revealed. The overwhelming number of assassinations in this book do not involve remote rifle shots; most assassinations have been carried out with bombs, knives or handguns. This is not to claim that works of fiction do not influence reality. Both Mehmet Ali Aca, who shot Pope John Paul II in 1981, and Yigal Amir, who murdered Yitzhak Rabin in 1995, were avid fans of Forsyths Day of the Jackal.

Assassinations are designed to have direct political and symbolic effects, which is why we know about most of them. But technically speaking most successful assassinations must surely be those where it remains open to doubt whether the victim was assassinated at all. Air crashes over deep sea or rugged mountains are ideal since recovery of the physical evidence is very arduous. In 1955 Kuomintang nationalist agents in Hong Kong conspired to blow up Chinese Premier Zhou Enlai in a chartered Lockheed Constellation aircraft called Kashmir Princess as he flew from Bombay via Hong Kong to Jakarta. Fortunately for Zhou he missed the flight because of suspected appendicitis, though sixteen of his delegation died in the crash over the South China Sea which three people survived. The main suspect, a janitor at Hong Kong Aircraft Engineering Co. called Chow Tse-ming (he had three aliases), fled to Taiwan. A good example of an assassination that may or may not have happened at all, would be that of Chinas Vice Chairman Marshal Lin Biao, who in 1971 after plotting to assassinate Chairman Mao in a train wreck perished along with his wife and adult son in a plane crash in Mongolia as he sought to flee to the Soviet Union. Whether the plane was sabotaged or hit the ground while flying low trying to avoid radar remains a mystery. Likewise, there have been persistent claims that PLO Chairman Yasser Arafat was poisoned with polonium, after he was taken gravely ill at a dinner in his West Bank headquarters in October 2004, dying in a French hospital of a massive haemorrhagic stroke a month later. Israel denies having killed Arafat (though it plotted to kill him many times before then) and radiological tests on his remains nearly a decade after his death yielded differing results according to who commissioned the French, Russian and Swiss forensic pathologists. Others have pointed to Arafats chronic ill health or claim that he died of Aids, though the stroke seems the most probable cause of death.

Thriller writers have long been obsessed with elaborate conspiracies to assassinate politicians; one of the finest is Eric Amblers Judgement on Deltchev, his 1951 novel set in an unnamed Balkan country. In the political struggle between the Agrarian Party which Deltchev leads and the Communists, it is increasingly unclear to the perplexed foreign narrator who is trying to assassinate whom. The killing of Julius Caesar shows us what a real conspiracy looks like: a conspiracy of elite social equals, where the secret stayed within the group until they publicly exulted in what they had done. There is nothing to suggest that something similar underlay the slaying of the Kennedys or Martin Luther King. Lee Harvey Oswald was a frustrated man with large pretensions who wanted his hour in the limelight, while King was killed by a racist criminal who sought a bounty. The shooting of Archduke Franz Ferdinand did not spark the First World War. The Austro-Hungarians (and Germans) would have found other pretexts for war with Serbia (and France and Russia); indeed on 31 July 1914 the German Kaiser told the Austrians not to bother with war with puny Serbia but to focus on their main event. Even if Archduke Franz Ferdinand had lived, he might well have caused a war with Serbia himself. But some killings would have had major repercussions. Killing Hitler in November 1939, as Georg Elser nearly did, would have had huge global consequences and prevented many millions of deaths. Only moral absolutists would object to such an outcome.