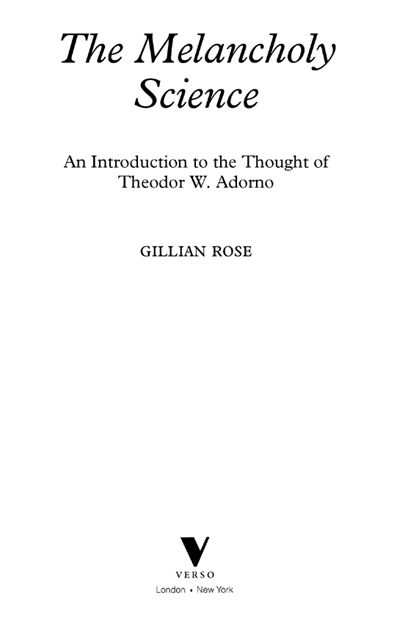

This paperback edition published by Verso 2014

First published by Macmillan Press Ltd 1978

Gillian Rose 1978, 2014

All rights reserved

The moral rights of the author have been asserted

Verso

UK: 6 Meard Street, London W1F 0EG

US: 20 Jay Street, Suite 1010, Brooklyn, NY 11201

www.versobooks.com

Verso is the imprint of New Left Books

ISBN-13: 978-1-78168-152-7

eBook ISBN: 978-1-78168-206-7

eISBN (UK): 978-1-78168-515-0

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

A catalog record for this book is available from the Library of Congress

v3.1

Acknowledgements

Many people have inspired, helped and criticised this work at various stages. I wish to thank especially Sir Isaiah Berlin, Julius Carlebach, Leszek Kolakowski, Steven Lukes and Sabine MacCormack.

I wish to thank the following people who read and commented on all or part of the manuscript in its final stages: Zev Barbu, Tom Bottomore, Frank Glover-Smith, E. F. N. Jephcott.

In addition I wish to thank Ulrike Meinhof, who checked all my translations and retranslations from the German, and Rogers Ragavan who gave me unstinting assistance in secretarial and practical matters. I am also grateful to the Librarian of St Antonys College, Oxford, for her patience in supplying books over the past few years, and to St Antonys College for their support. I wish to thank the Social Science Research Council, the University of Sussex and the Deutsche Akademische Austauschdienst for financial help during the course of the research, which was partly conducted at the Free University, West Berlin, and at the University of Constance, West Germany.

My special thanks are given to Stefan Collini, Herminio Martins, John Raffan and Jacqueline Rose.

Preface

The melancholy science which this book expounds is not a pessimistic science. By introducing Minima Moralia as an offering from his melancholy science an inversion of Nietzsches joyful science Adorno undermines and inverts the sanguine and total claims of philosophy and sociology, and rejects any dichotomy such as optimistic/pessimistic for it implies an inherently fixed and static view.

Adornos work draws on traditions inherited from Marxian and non-Marxian criticism of Hegels philosophy, and on the pre-Marxian writings of Lukcs and of Benjamin as much as on their Marxian writings. Interpretation of Adorno suffers when his aims and achievements are related solely to Marx or to a Marxian tradition which is sometimes undefined and sometimes overdefined, and, equally, when he is judged solely as a sociologist. Here, Adornos thought is introduced and discussed in its own right, immanently, to use his own term. Where appropriate, Adornos engagement with and transformation of the many intellectual traditions which inform his work is examined.

Adornos thought depends fundamentally on the category of reification. This category has attained a strangely dominant role in much neo-Marxist and phenomenological literature and in recent sociological amalgams of these two traditions. It is used to evoke, often by mere suggestion or allusion, a very peculiar and complex epistemological setting which is rarely examined further or justified. In the Marxian tradition reification is most often employed as a way of generalising Marxs theory of value with the aim of producing a critical theory of social institutions and of culture, but frequently any critical force is lost in the process of generalisation.

Adornos work, the most ambitious and important to have emerged from the Institute for Social Research before 1969, is the most abstruse, and, in spite of its great influence, still the most misunderstood. This is partly a result of its deliberately paradoxical, polemical and fractured nature which has made it eminently quotable but egregiously misconstruable. Yet, as I try to show, Adornos uvre forms a unity even though it is composed of fragments. In the last five years all the major works and many of the minor works of Adorno, Lukcs and Benjamin have been translated or are in the process of being translated into English. In spite of this increasing recognition of their importance there exists as yet little systematic study of their work.

I have not attempted to be exhaustive in my treatment of Adornos work. In particular, his writings on music, which constitute over half of his published work, do not receive detailed attention. Although Adorno acknowledged the importance of his collaboration with Horkheimer, his debates with Lukcs and with Benjamin reveal more of the inspiration which structures his thought, and I have therefore concentrated on those aspects. While I argue that Adornos texts must be read from a methodological point of view with close attention to stylistic features, I have, nevertheless, reconstructed his ideas in standard expository format.

1

The Crisis in Culture

The Frankfurt School, 192350

All the tensions within the German academic community which accompanied the changes in political, cultural and intellectual life in Germany since 1890 were reproduced in the Institute for Social Research from its inception in Frankfurt in 1923. By this very definition the crisis was deplored yet exacerbated. The Institute carried these tensions with it into exile and when it returned to Germany after the war and found itself the sole heir to a discredited tradition the inherited tensions became even more acute. These tensions are evident in the work of most of the Schools members, and most clearly, self-consciously and importantly in the work of Theodor W. Adorno.

From 1890 the German academic community reacted in a variety of ways to the sudden and momentous development of capitalism in Germany, and to the new role of Germany in the world. This resulted in disillusionment with various scientific and philosophical methods, and the pedagogical and philosophical revival which followed occurred across the political spectrum, to the extent that the spectrum was represented in the universities. The different attempts to re-engage learning and reinvigorate German life have been indicted for their political navety and irresponsibility. This transposition became the basis for its subsequent achievements. Yet time and time again, the history of the School reveals this tension: as an institution, it reaffirmed and reinforced those aspects of German life which it criticised and aimed to change, just as it reaffirmed and reinforced those aspects of the intellectual universe which it criticised and aimed to change. Only if this is realised can the goals, achievements and failures of the School and of the work of Adorno be defined and assessed.

During the thirties, first in Germany and later in exile, the School is best examined in the same light. Under Horkheimers directorship, it avoided the pedantry and conservatism of the universities, while engaging in sociological research which united theoretical and empirical inquiry. Yet the Frankfurt School, although implicated in this more than its own rhetoric or scholarship to date suggests, deserves different treatment too. The special case of the School has always rested on its particular fusion of the Idealism, which arose in opposition to neo-Kantianism, with the revival of Marxism after the First World War.

It may be said that the members of the School were addressing themselves in their collaboration during the upheavals of the thirties to the question which Marx asked at the end of the