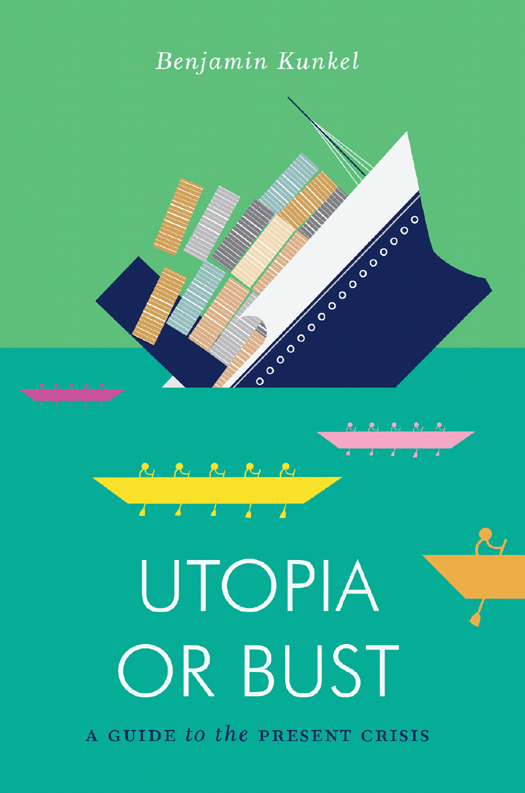

The Jacobin series features short interrogations of politics, economics, and culture from a socialist perspective, as an avenue to radical political practice. The books offer critical analysis and engagement with the history and ideas of the Left in an accessible format.

The series is a collaboration between Verso Books and Jacobin magazine, which is published quarterly in print and online at jacobinmag.com.

Other titles in this series available from Verso Books:

Playing the Whore by Melissa Gira Grant

Strike for America by Micah Vetricht

First published by Verso 2014

Benjamin Kunkel 2014

appeared first, in slightly different form, in the London Review of Books (February 3, 2011; April 22, 2010; 4, May 10, 2012; August 8, 2013 respectively).

appeared first in n+1 (June 4, 2010).

appeared first in the New Statesman (September 27, 2012).

All rights reserved

The moral rights of the author have been asserted

Verso

UK: 6 Meard Street, London W1F 0EG

US: 20 Jay Street, Suite 1010, Brooklyn, NY 11201

www.versobooks.com

Verso is the imprint of New Left Books

ISBN-13: 978-1-78168-327-9 (PBK)

eISBN-13: 978-1-78168-328-6 (US)

eISBN-13: 978-1-78168-637-9 (UK)

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

A catalog record for this book is available from the Library of Congress

v3.1

For

who can use it

It was thenceforth no longer a question whether this theorem or that was true, but whether it was useful to capital or harmful, expedient or inexpedient, politically dangerous or not. In place of disinterested inquirers, there were hired prize fighters; in place of genuine scientific research, the bad conscience and the evil intent of apologetic.

Karl Marx, afterword to the second

German edition of Capital

What ever happened to Political Economy, leaving me here?

John Berryman, Dream Song 84

Contents

Introduction

To the disappointment of friends who would prefer to read my fictionas well as of my literary agent, who would prefer to sell itI seem to have become a Marxist public intellectual. Making matters worse, the relevant public has been a small one consisting of readers of the two publications, the London Review of Books and n+1, where all but one of the essays here first appeared, and my self-appointed role has likewise been modest. The essays attempt no original contribution to Marxist, or what you might call Marxish, thought. They simply offer basic introductions, with some critical comments, to a handful of contemporary thinkers on the left: three Marxists at work in their respective fields of geography, history, and cultural criticism; an anthropologist of anarchist convictions; and two philosophers who might be called neo-communists. These are meanwhile only a few of the present-day figures most attractive or interesting to me, and even if my discussion of their work does something to clarify the economic and cultural features of the ongoing capitalist crisis, several of the books deficiencies will be more readily apparent than this achievement. The essays here no more than allude to the ecological and political dimensions of the crisis that burst into view in 2008, and they ignore altogether its uneven impact on different countries, genders, generations, races.

The purpose of this modest explanatory volume is nevertheless immodest. The idea is to contribute something in the way of intellectual orientation to the project of replacing a capitalism bent on social polarization, the hollowing out of democracy, and ecological ruin with another, better order. This would be one adapted to collective survival and well-being, and marked by public ownership of important economic and financial institutions, by real as well as formal democratic capacities, and by social equalityall of which together would promise a renewal of culture in both the narrowly aesthetic and the broadly anthropological meanings of the term.

Theory, and writing about theorists, brings no victories by itself. Nor is there any need for everyone on the left or moving leftwards to converge on the same understanding of late capitalism, in the sense of recent or in decline, before anything can be done to make it late as in recently departed. Imperfect understanding is the lot of all political actors. Still, for at least a generation now, not only the broad public but many radicals themselves have felt uncertain that the left possessed a basic analysis of contemporary capitalism, let alone a program for its replacement. This intellectual disorientation has thinned our ranks and abetted our organizational disarray. Over the same period the comparative ideological coherence of our neoliberal opponents gave them an invaluable advantage in securing public assent to their policies or, failing that, resignation. Gaining a clearer idea of the present system should help us to challenge and one day overcome it. The essays in this short book about a number of other books, several of them long and dense, are collected here for whatever they can add to the effort. Social injustice and economic insecuritybland terms for the calamities they namewould make overcoming capitalism urgent enough even if the system could boast a stable ecological footing; obviously, it cannot.

The odds of political success may not look particularly good at the moment. But the defects of global capitalism have become so plain to the eyeif still, for many minds, too mysterious in their causes and too inevitable in their effectsthat the odds appear better than a few years ago. The crisis has not only sharpened anxieties but introduced new hopes, most spectacularly in 2011, year of the Arab Spring, of huge indignant crowds in European plazas, and of Occupy Wall Street. Today as I write in the summer of 2013, kindred movements have emerged, massively and spontaneously, in the streets of Turkey and Brazil. Over recent years my own political excitement, anxious and optimistic at once, has led to me to spend as much time thinking about global capitalism and its theorists as about the fictional characters in whose company Id expected, as a novelist, to spend more of my time. That is one explanation for the existence of this book.

So are you an autodidactic political economist now? a friend asked the other day. Im no economist at all, but the question catches something of whats happened. In 2005, with the publication of my first novel, I suddenly became a successful young writer: enthusiastic reviews; a brief life on the best-seller lists; translation into a dozen languages; and an option deal from a Hollywood producer with deep pockets. These very welcome developments coincided with the worst depressive episode of my adult life. I cant say what caused it, but I remember thinking of the poet Philip Larkins line about bursting into fulfillments desolate attic.

Why should it have felt desolate? Id always wanted to write novels and was now in a good position to go on doing just that. Part of the trouble seems to have been that your own fulfillment is no one elses, and therefore not even quite your own. Surely another part was that even the so-called systems-novelists I especially admired when I was younger alluded to the principal system, the economic one, more than they described or explained it: a trait of their work that had become less satisfying to me, without my knowing how to do things differently in my own. For now let it be enough to confess that I would like to live in a more fulfilling society or civilization than a self-destructive capitalist one (where, as it happens, the leading cause of death for middle-aged men in the richest country of the world is now suicide) and that these essays have been, among other things, a way of saying so. If theyre assembled here in hopes of contributing to left politics, their origin probably lies in a wish to find, outside of art, some of the artistic satisfaction that comes of expressing such deep concerns that you cannot name their source.