BANNING DDT

BANNING

DDT

HOW CITIZEN ACTIVISTS

IN WISCONSIN

LED THE WAY

Bill Berry

WISCONSIN HISTORICAL SOCIETY PRESS

Published by the Wisconsin Historical Society Press

Publishers since 1855

2014 by the State Historical Society of Wisconsin

E-book edition 2014

Publication of this book was made possible in part by a grant from the Alice E. Smith fellowship fund.

For permission to reuse material from Banning DDT, ISBN: 978-0-87020-644-3, ebook ISBN: 978-0-87020-645-0, please access www.copyright.com or contact the Copyright Clearance Center, Inc. (CCC), 222 Rosewood Drive, Danvers, MA 01923, 978-750-8400. CCC is a not-for-profit organization that provides licenses and registration for a variety of users.

wisconsinhistory.org

Photographs identified with WHi or WHS are from the Societys collections; address requests to reproduce these photos to the Visual Materials Archivist at the Wisconsin Historical Society, 816 State Street, Madison, WI 53706.

Cover design by Anders Hanson

18 17 16 15 14 1 2 3 4 5

The Library of Congress has cataloged the printed edition as follows:

Berry, Bill, 1951

Banning DDT : how citizen activists in Wisconsin led the way / Bill Berry.

pages cm

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-0-87020-644-3 (pbk. : alk. paper)ISBN 978-0-87020-645-0 (ebook)

1. DDT (Insecticide)Environmental aspectsHistory20th century. 2. Environmental protectionWisconsinCitizen participationHistory20th century. 3. EnvironmentalismUnited StatesHistory20th century. I. Title.

TD196.P38B47 2014

363.738498dc23

2013036819

To members of my family, who offered encouragement and support

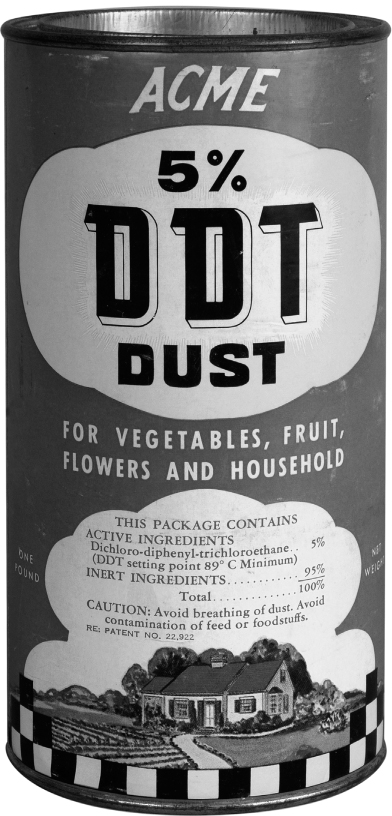

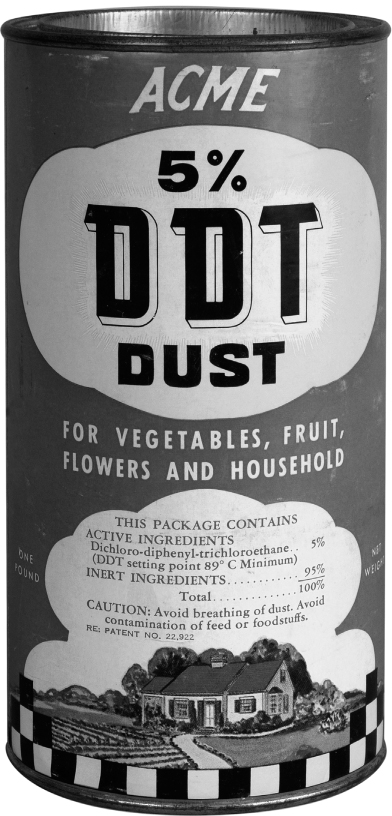

Soldiers in World War II carried DDT dust cans with them to fend off a variety of insect pests. After the war, DDT was a popular household and garden product. WHS Museum 1999.143.20; photo by Joel Heiman

CONTENTS

FOREWORD

T HIS ACCOUNT OF CITIZEN ACTIVISM IN WISCONSIN IN THE 1960s is a powerful testament to the effectiveness of grassroots advocacy in creating substantive social change. The players in this drama are not corporate titans or conservation NGO leaders, but concerned citizens and dedicated scientists whose passion and determination helped pave the way to banning DDT.

Its an important story because DDT would not have been banned quicklyor maybe at allwithout citizens and scientists committed to participatory democracy. Author Bill Berrys focus on ordinary citizens rather than policy makers is something you seldom see in history books. Here Senator Gaylord Nelson is a bit player while Lorrie Otto, a Milwaukee-area housewife, is a star.

As has been clear since the National Audubon Society launched more than a hundred years ago, a handful of dedicated citizens can and do make a difference. Audubons roots are in a small group of men and primarily women who came together to protect birds from slaughter at the hands of plume hunters. This happened at a time when hats sporting featherssometimes even entire birdswere the height of fashion. It was these early conservationists who founded the National Audubon Society.

Today, Audubon continues its legacy of protecting birds and other wildlife through a combination of science, advocacy, and grassroots activism. Organizations like Audubon depend on people like Lorrie Otto to make collective action possible. If we are going to accomplish any of our conservation goals, people must remember the successes of committed Americans like Ottoand the others whose stories are told in these pages, including scientist Joseph Hickey, her fellow Audubon Medal recipientin driving policy change.

This account also shines a light on the role birds can play in signaling when something is wrong in our environment. Among the earliest to see that something was wrong after neighborhood trees were sprayed with DDT were bird-watchers and gardeners in cities and suburbs who noticed the death and disappearance of songbirds. In fact, as Mr. Berry points out in this account, bird-watchers had issued warnings about the environmental impacts of DDT as early as 1945, when Richard Pough, then with the National Audubon Society, raised the alarm in the New Yorker. But it was the publication of Rachel Carsons world-changing Silent Spring in 1962 that galvanized a nation of grassroots activists and launched the modern environmental movement.

Scientists tell us that, increasingly, nature is out of sync. Birds are arriving too early at their summering grounds to find adequate food and many species are running out of habitat. We are seeing many of the effects of climate change sooner than we expected. The challenges we face now are bigger than ever before. Whether youre concerned about birds, biodiversity, or people, every single thing you do can make a difference.

So, raise your voice for birds, for people, and for the future of our planet. Inspired examples of making a difference can be found in this story of engaged citizen activists who, through a combination of passion and grassroots activism, sought and achieved change in Wisconsin and beyond.

DAVID YARNOLD,

PRESIDENT & CEO, NATIONAL AUDUBON SOCIETY

PREFACE

O NE DAY IN 2008, WHILE WALKING THROUGH CHERRY CREEK Canyon in New Mexico with a lifelong friend who made his living as a wildlife biologist, we heard the fierce screams of a couple of peregrine falcons echo off ancient rock formations.

We strained to see the birds, but to no avail. The screams and streaks of whitewash below falcon perches would have to do that day. That didnt diminish the thrill. It seemed almost fitting that the birds should take on this ghostly presence.

That day we were on a bird-watching tour led by a National Audubon Society guide. He confirmed what we already knew: the peregrines were making a comeback decades after the use of the pesticide DDTdichlorodiphenyltrichloroethanehad been banned in the United States.

Cherry Creek Canyon is near the Gila Wilderness, the nations first wilderness area, for which Aldo Leopold had lobbied in the days he worked for the US Forest Service. It was designated so in 1924, the same year Leopold left the Southwest for a position at the US Forest Products Laboratory in Madison, Wisconsin. In 1933, he was named professor of game management in the Department of Agricultural Economics of the College of Agriculture at the University of Wisconsin in Madison.

The story of Leopold and his classic book, A Sand County Almanac, is oft told. The power of the collection of essays, penned mostly on family outings to the shack and its surrounding worn-out farmland where Leopold set out to undertake an exercise in ecological restoration, still resonates across the world. Leopold died in 1948, and the book was published a year later, but his concept of a land ethic, or a responsible relationship between people and the land they inhabit, guides the work of natural resources professionals and conservation-minded citizens to this day. Leopolds impact is felt in the pages of this book. Although he was dead nearly two decades before the use of DDT was challenged in Wisconsin, his name and lessons were often cited by a gutsy band of early citizen environmental activists. Among them were scientists who had worked with or known Leopold. His lessons may have helped them step out of the comfort zone that academia can provide and into the public fray, sometimes with painful consequences.

It was Leopold who, in 1947, convinced a lanky easterner he had advised as a graduate student to join him as a professor in Madison. The man was Joseph Hickey, and his name is now forever tied to the Wisconsin DDT battles of the late 1960s. Hickey was a lifelong bird-watcher whose childhood companions in the endeavor included Roger Tory Peterson, who would become one of Americas best-known naturalists and artists, and Allan Cruickshank, who would establish himself as a pioneering wildlife photographer. Hickey also had a special affection for the peregrine falcon. This affinity would prove a crucial link in the effort to understand the impacts DDT was having on the web of life.

Next page