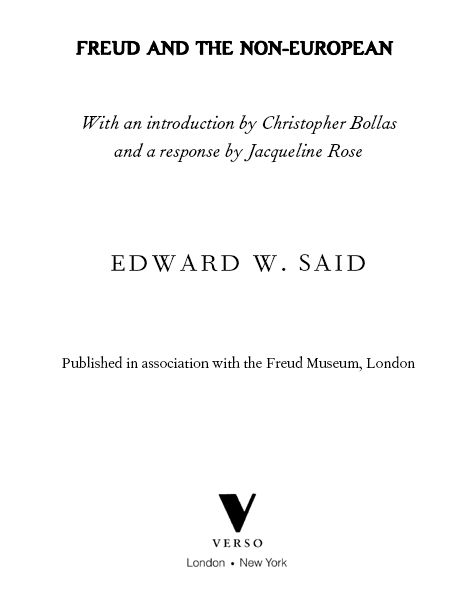

This edition published by Verso 2014

First published by Verso, in association with the Freud Museum, London, 2003

Edward Said 2003, 2004, 2014

Introduction Christopher Bollas 2003, 2004, 2014

Response Jacqueline Rose 2003, 2004, 2014

All rights reserved

The moral rights of the authors have been asserted

Verso

UK: 6 Meard Street, London W1F 0EG

US: 20 Jay Street, Suite 1010, Brooklyn, NY 11201

www.versobooks.com

Verso is the imprint of New Left Books

ISBN-13: 978-1-78168-145-9

eBook ISBN: 978-1-78168-199-2

eISBN (UK): 978-1-78168-508-2

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

A catalog record for this book is available from the Library of Congress

v3.1

CONTENTS

INTRODUCING EDWARD SAID

Christopher Bollas

FREUD AND THE NON-EUROPEAN

Edward W. Said

INTRODUCING JACQUELINE ROSE

Christopher Bollas

RESPONSE TO EDWARD SAID

Jacqueline Rose

INTRODUCING EDWARD SAID

Christopher Bollas

O n behalf of the Freud Museum of London I am pleased to welcome all of you to this important occasion: to hear Professor Edward Saids talk on Freud and the Non-European, to be discussed later by Professor Jacqueline Rose, whom I shall introduce before her response.

Well, it is no new experience for Edward Said to be in exile, and so it is here, following in Freuds footsteps (in certain respects), that he is to speak in London rather than Vienna; but those who have studied with him, or know him personally, well appreciate his remarkable yet natural way of transforming injustice into learned protest. Provided that the exile refuses to sit on the sidelines nursing a wound, he writes in Reflections on Exile, there are things to be learned: he or she must cultivate a scrupulous (not indulgent or sulky) subjectivity.

Said was born in West Jerusalem of parents who ordinarily resided in Cairo but travelled to Palestine often to see family and friends. His first deep contact with the fate of the exile was in 1948, when his family was driven from Palestine, and he was not to return for forty-five years. Perhaps it was his Aunt Nabihas energy and determination to address the desolations of being without a country or a place to return to that inscribed itself in that gathering momentum that was to become Said the international figure, but he has alluded to the importance of his move to the United States first to boarding school, and then to Princeton University which not only widened his horizons, but became an object to be used, if I may allude to Winnicotts notion of creativity and the use of the object through which further to articulate his remarkable sensibility.

At Columbia University as a young assistant professor, he wrote his first book on Joseph Conrad (1966), and between then and now I think he has written at least twenty books, translated into over thirty-six languages.

The 1967 war shook him from even an imaginary future in the academic ivory tower, and this event sponsored a new line of thought in his life that would realize itself most clearly in his book Orientalism, which examined, among other things, European writings on the Orient, illuminating the politics of literary representation.

(Those of you here who are interested in psychoanalytical studies will want to read his analysis of Freuds Interpretation of Dreams in Beginnings, as I think it is a fascinating literary analysis of Freuds book as enacting what it argues.)

In 1977 Said was elected to the Palestine National Council, where he remained until 1991, when he resigned. As most of you here know, he has been a brilliant, tireless and courageous spokesman for the Palestinian cause. The Question of Palestine was published in 1979.violence seeks to maintain sanity for its people through the insistence that the self exists even as the oppressors seek to deny it, something that, of course, the Jewish people know only too well through the catastrophe that was the Holocaust.

Some of his subsequent writings examine the provincialism of academic studies, or what we might think of as the provincialist defence against the multicultural: in psychoanalysis, a form of splitting of the ego in which any self resides happily inside a mere fragment of itself, in order to remain untroubled by all the other parts of the total picture.

Edward Said is also a fine pianist, and became the music critic of a prominent American publication, The Nation. He has collaborated with Daniel Barenboim and the Chicago Symphony Orchestra in a new production of Beethovens Fidelio, for which he wrote a new English text to replace the spoken dialogue; in addition, he conducted a workshop with Barenboim and Yo-Yo Ma for young Arab and Israeli musicians in Weimar, Germany. He has written on many musical subjects, his essays on Glenn Gould are wonderful, and he has taken a musical act the contrapuntal and put it into the world of political and literary discourse:

We could certainly transfer his invention to psychoanalytical theory, proposing the psychic contrapuntal which recognizes the benefit of movement outside of ones primary place, to a new location from which the self, and its others, are seen in a different light. Moving from the maternal order to the paternal order, from the image-sense world of the infantile place to the symbolic order of language, may be our first taste of exile, one that seems to haunt and yet energize much of Prousts writing. In this respect, we may all be exiles of a sort perhaps this is why even those of us who have not shared the terrible fate of those driven from home can none the less grasp their fate empathically.

Edward Said is a University Professor at Columbia University. He has delivered the Reith Lectures for the He is currently working on The Relevance of Humanism in Contemporary America, to be published in 2002 by Columbia University Press.

FREUD AND THE NON-EUROPEAN

Edward W. Said

T here are two ways in which I shall be using the term non-European in this lecture one that applies to Freuds own time; the other to the period after his death in 1939. Both are deeply relevant to a reading of his work today. One, of course, is a simple designation of the world beyond Freuds own as a Viennese-Jewish scientist, philosopher and intellectual who lived and worked his entire life in either Austria or England. No one who has read and been influenced by Freuds extraordinary work has failed to be impressed by the remarkable range of his erudition, especially in literature and the history of culture. But by the same token, one is very struck by the fact that beyond the confines of Europe, Freuds awareness of other cultures (with perhaps one exception, that of Egypt) is inflected, and, indeed shaped by his education in the Judaeo-Christian tradition, particularly the humanistic and scientific assumptions that give it its peculiarly Western stamp. This is something that doesnt so much limit Freud in an uninteresting way as identify him as belonging to a place and time that were still not tremendously bothered by what today, in the current postmodern, poststructuralist, postcolonialist jargon, we would call the problems of the Other. Of course Freud was deeply gripped by what stands outside the limits of reason, convention, and, of course, consciousness: his whole work in that sense is about the Other, but always about an Other recognizable mainly to readers who are well acquainted with the classics of Graeco-Roman and Hebrew Antiquity and what was later to derive from them in the various modern European languages, literatures, sciences, religions and cultures with which he himself was well acquainted.