BECOMING FREUD

Becoming Freud

The Making of a Psychoanalyst

ADAM PHILLIPS

Copyright 2014 by Adam Phillips.

All rights reserved.

This book may not be reproduced, in whole or in part, including illustrations, in any form (beyond that copying permitted by Sections 107 and 108 of the U.S. Copyright Law and except by reviewers for the public press), without written permission from the publishers.

Yale University Press books may be purchased in quantity for educational, business, or promotional use. For information, please e-mail sales.press@yale.edu (U.S. office) or sales@yaleup.co.uk (U.K. office).

Set in Janson type by Integrated Publishing Solutions, Grand Rapids, Michigan.

Printed in the United States of America.

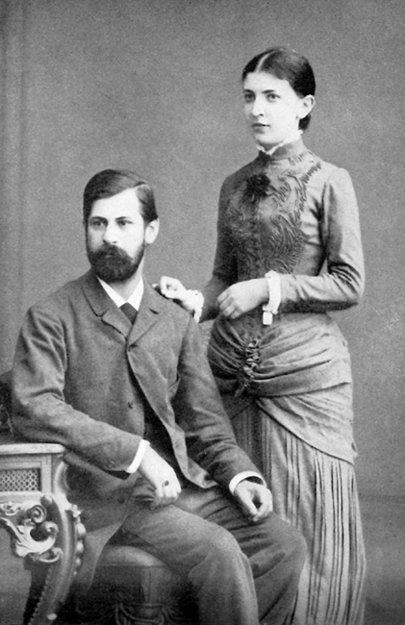

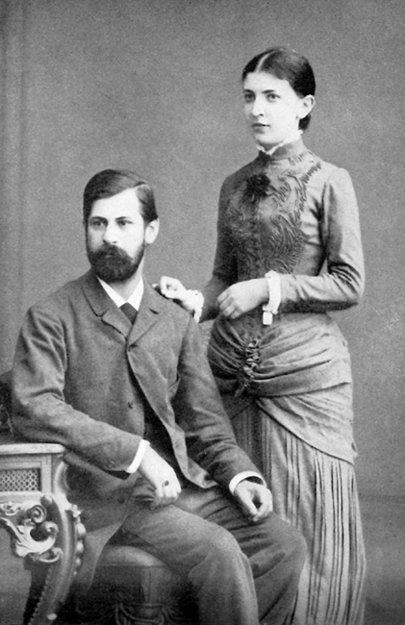

Frontispiece: Sigmund Freud with Martha Bernays, 1883.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Phillips, Adam, 1964

Becoming Freud : the making of a psychoanalyst / Adam Phillips.

Pages cm.(Jewish lives)

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-0-300-15866-3 (hardback)

1. Freud, Sigmund, 18561939. 2. PsychoanalystsBiography. I. Title.

BF109.F74P485 2014

150.19'52092dc23

[B]

2013048573

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

This paper meets the requirements of ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992

(Permanence of Paper).

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

For Stephen Greenblatt and Ramie Targoff

... these psychoanalytical matters are intelligible only if presented in pretty full and complete detail, just as an analysis really gets going only when the patient descends to minute details from the abstractions which are their surrogate. Thus discretion is incompatible with a satisfactory description of an analysis; to provide the latter one would have to be unscrupulous, give away, betray, behave like an artist who buys paints with his wifes house-keeping money or uses the furniture as firewood to warm the studio for his model. Without a trace of that kind of unscrupulousness the job cannot be done.

Freud to Oscar Pfister, 5 June 1910

CONTENTS

1

Freuds Impossible Life:

An Introduction

What right does my present have to speak of my past? Has my present some advantage over my past?

Roland Barthes by Roland Barthes

THE STORY OF FREUDS LIFE is easily told. He was born in 1856 in Freiberg in Moravia, a town now called Pribor in the Czech Republic, but then part of the Hapsburg Empire. One hundred and fifty miles north of Vienna, it was a small market town, almost entirely Catholic but with a tiny Jewish community. Freuds father was a merchant, trading mostly in wool, and Sigmund Freud was the first of seven childrenfive daughters and two sonsof his fathers second (and possibly third) marriage to a woman twenty years younger than himself. Jacob Freud had two sons from a previous marriage. His business collapsed when Freud was three and a half, and the family moved first to Leipzig in Germany for a year and then on to Vienna, where Freud lived until 1938. Freud went to the Sperl Gymnasium, a school in Vienna in 1865, and after briefly considering a career in law Freud studied medicine at the University of Vienna between 1873 and 1882, specializing in his third year in Comparative Anatomy. After research in physiology but with no obvious professional prospectshe went in 1885 to study for several months in Paris with the great neurologist Charcot, returning in 1886 to set up his own private practice as Docent in Neuropathology. In the same year, after a four year engagement, he married Martha Bernays, a woman five years younger than himself and the granddaughter of a distinguished German-Jewish family (her grandfather had been the Chief Rabbi of Hamburg). The couple had six children, three daughters and three sons, in fairly quick succession. In 1896 Freuds father died at the age of eighty-one.

Through extensive clinical work, at first using the method of hypnotism on so-called hysterical patients; and through a series of passionate relationships with menmost notably the physician Josef Breuer (b. 1842), whom he met in the late 1870s, and Wilhelm Fliess (b. 1858), an ear, nose, and throat specialist from Berlin whom he met in 1887; and then, after the turn of the century with younger men, most notably Carl Jung (b. 1875), Alfred Adler (b. 1870), Karl Abraham (b. 1877), Otto Rank (b. 1884), and Sandor Ferenczi (b. 1873)Freud invented the clinical practice of psychoanalysis (he first used the term in 1896). Psychoanalysis was, as one early patient called it, a talking cure, the doctor and the patient doing nothing but talk together. The patient lay on a couch, with the analyst sitting behind him, and was instructed to free-associate i.e., say whatever came into his head, including his dreams, undistracted by the analysts responses, with the doctor clarifying and interpreting and reconstructing the patients childhood experiences; but not using drugs or physical contact as part of the treatment. The aim was the modification of symptoms and the alleviation of suffering through redescription.

A prolific writer, from 1886 to his death in 1939, Freud published what in the Standard Editionthe official translation of nearly all his work into Englishbecame twenty-three volumes of theoretical and clinical writing, and he wrote thousands of letters. It was through Studies On Hysteria (written with Breuer, 1895), The Interpretation of Dreams (1900), Three Essays on the Theory of Sexuality (1905), Jokes and Their Relation to the Unconscious (1905), The Psychopathology of Everyday Life (1905), The Future of an Illusion (1927), and Civilisation and Its Discontents (1929) that Freud made his name.

As Freuds work became known beyond the confines of Vienna through his writing and his personal influence, the Psychoanalytic Movement, as it was soon called, grew out of the informal Wednesday Evening Meetings started by Freud in 1902 for curious and interested fellow professionals. The first International Psycho-Analytical Congress was held in Salzburg in 1908, and in 1910 the International Psycho-Analytical Association was founded. In 1909 Freud made his first and only trip to America to lecture at Clark University in Worcester, Massachusetts.

In 1917, during the First World War, in which his sons saw active service, Freud discovered a growth on his palate which was finally diagnosed in 1923 as cancer which, despite operations, he suffered from intermittently for the rest of his life, though he continued to work to the very end. In 1919 his favourite daughter Sophie died of influenza at age twenty-six, and in 1930 his mother died at the age of ninety-five. In 1938, after living and working in Vienna for nearly sixty years, Freud fled to London from the Nazis with his daughter Anna, also a psychoanalyst, where he died in 1939.

to great menPlato, Moses, Hannibal, Michelangelo, Leonardo da Vinci, Goethe, Shakespeare, among othersmost of them artists; and all of them, in Freuds account, men who defined their moment, not men struggling to assimilate to their societies, like many of the Jews of Freuds generation; self-defining men, men pursuing their own truths against the constraints of tradition. In the young Freuds myth of his own heroism, created in The Interpretation of Dreams, he was a man who would face, in a new way, the facts of his own life (he uses as his epigraph to the book a lineappropriately given his ambitionsfrom Virgils

Next page