Copyright 2013 by Princeton University Press

Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs CC BY-NC-ND

Requests for permission to modify material from this work should be sent to Permissions, Princeton University Press

Published by Princeton University Press, 41 William Street, Princeton, New Jersey 08540

In the United Kingdom: Princeton University Press, 6 Oxford Street, Woodstock, Oxfordshire OX20 1TW

press.princeton.edu

All Rights Reserved

At the time of writing of this book, the references to Internet Web sites (URLs) were accurate. Neither the author nor Princeton University Press is responsible for URLs that may have expired or changed since the manuscript was prepared.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Coleman, E. Gabriella, 1973

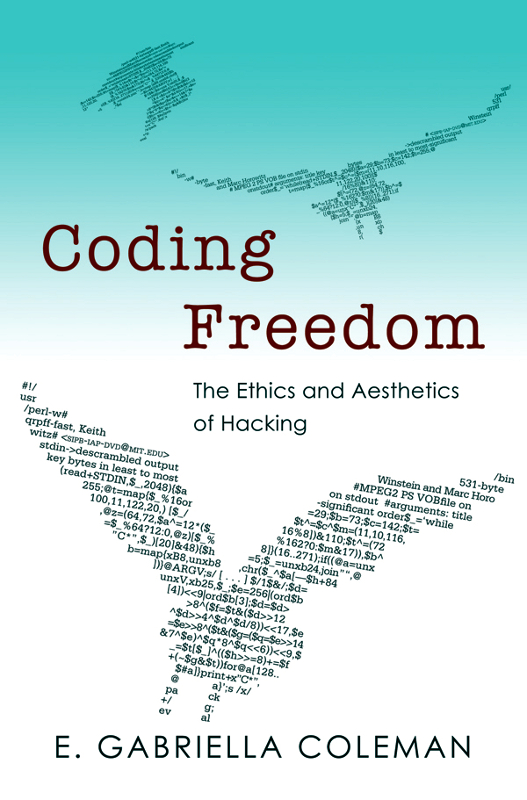

Coding freedom : the ethics and aesthetics of hacking / E. Gabriella Coleman.

p. cm.

Includes .

ISBN 978-0-691-14460-3 (hbk. : alk. paper)ISBN 978-0-691-14461-0 (pbk. : alk. paper) ISBN 978-140-08452931(e-Book) 1. Computer hackers. 2. Computer programmers. 3. Computer programmingMoral and ethical aspects. 4. Computer programmingSocial aspects. 5. Intellectual freedom. I. Title.

HD8039.D37C65 2012

174.90051--dc232012031422

British Library Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available

This book is distributed in the hope that it will be useful, but WITHOUT ANY WARRANTY; without even the implied warranty of MERCHANTABILITY or FITNESS FOR A PARTICULAR PURPOSE

We must be free not because we claim freedom, but because we practice it.

William Faulkner, On Fear: The South in Labor

Without models, its hard to work; without a context, difficult to evaluate; without peers, nearly impossible to speak.

Joanna Russ, How to Suppress Womans Writing

CONTENTS

T his project marks the culmination of a multiyear, multicity endeavor that commenced in earnest during graduate school, found its first stable expression in a dissertation, and has, over a decade later, fully realized itself with this book. During this long period, over the various stages of this project, many people have left their mark in so many countless ways. Their support, interventions, comments, and presence have not only improved the quality of this work but also simply made it possible. This book could not have been written without all of you, and for that I am deeply grateful.

In 1996, at the time of my first exposure to Linux, I was unable to glean its significance. I could not comprehend why a friend was so enthused to have received a CD in the mail equipped with Slackware, a Linux distribution. To be frank, my friends excitement about software was not only incomprehensible; it also was puzzling. Thankfully about a year later, this person clued me in as to what makes this world extraordinary, doing so initially via my interest at the time: intellectual property law. If it were not for Patrick Crosby, who literally sat me down one day in 1997 to describe the existence of a novel licensing agreement, the GNU General Public License (GPL), I would have likely never embarked on the study of free software and eventually hackers. I am thrilled he decided that something dear to him would be of interest to me. And it was. I was floored to discover working alternatives to existing intellectual property instruments. After months of spending hour after hour online, week after week, reading about the flurry of exciting developments reported on Linux Weekly News, Kuro5hin, and Slashdot, it became clear to me that much more than the law was compelling about this world, and that I should turn this distractingly fascinating hobby into my dissertation topic or run the risk of never finishing graduate school. Now I not only know why Patrick was happy to have received the Slackware CD back in 1996and I found he was not alone, because many people have told me about the joy of discovering Slackwarebut also hope I can convey this passion for technology to others in the pages of this book.

Many moons ago in graduate school at the University of Chicago when I proposed switching projects, my advisers supported my heretical decision, although some warned me that I would have trouble landing a job in an anthropology department (they were right). Members of my dissertation committee have given invaluable insight and support. My cochairs, Jean Comaroff and John Kelly, elongated my project in the sense that they always asked me to think historically. Jean has also inspired me in so many ways, then and now. She is everything a scholar should be, so I thank her for being such a great mentor. Nadia Abu El-Haj encouraged me to examine the sociocultural mechanisms by which technoscience can act as the basis for broader societal transformation. I was extremely fortunate to have Gary Downey and Chris Kelty on board. In 1999, I was inspired by a talk that Gary gave at the American Anthropological Association meetings on the importance of positive critique, and I hope to have contributed to such a project here.

Chris, a geek anthropologist extraordinaire, has added to this project in innumerable ways. Because of his stellar work on free software, his comments have been breathlessly on target, and more than any other person, he has pushed this project to firmer, more coherent ground. His insistence on not only understanding the world but also (re)shaping it is inspiring, and I hope that I can one day follow in his footsteps. Although Patrice Riemens was not an official adviser, he nonetheless, like any hacker would, shared freely. His advice, especially pertaining to hacker politics, was as indispensable as the guidance from my official committee members.

Fieldwork, of course, is where the bulk of anthropological research occurs. For me, most of that took place in San Francisco, with a short stint in the Netherlands, and throughout copious time was spent online. While there were countless people who made my fieldwork possible, I have to single out three who really went out on a limb for me, over and over again: Seth Schoen, Praveen Sinha, and Zack Brown. I think each one of you knows how much you have helped me start, proceed with, and finish this project, and I am grateful from the bottom of my heart.

Many others have helped me understand with much greater depth what drives people to write free and open-source software (F/OSS). Among those in the Bay Area, I would like to especially thank Brian Behlendorf, Rick Moen, Karsten Self, Don Marti, Mike Higashi, and Evan Prodromou. Also, all the folks at the Electronic Frontier Foundation and Online Policy Group provided me with the invaluable opportunity of interning at their respective organizations. Will Doherty, in particular, deserves a special nod (even though he worked me so hard). Quan Yin also gave me the opportunity to volunteer at its acupuncture clinic, and perhaps more than any other experience, this one kept everything in place and perspective. My Bay Area roommates, Linda Graham and Nikki Ford, supplied me with an endless stream of support.

Next page