First published by Chronos Books, 2014

Chronos Books is an imprint of John Hunt Publishing Ltd., Laurel House, Station Approach, Alresford, Hants, SO24 9JH, UK

www.johnhuntpublishing.com

For distributor details and how to order please visit the Ordering section on our website.

Text copyright: Merilyn Moos 2013

ISBN: 978 1 78279 677 0

All rights reserved. Except for brief quotations in critical articles or reviews, no part of this book may be reproduced in any manner without prior written permission from the publishers.

The rights of Merilyn Moos as author have been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

Design: Stuart Davies

Printed and bound by CPI Group (UK) Ltd, Croydon, CR0 4YY

We operate a distinctive and ethical publishing philosophy in all areas of our business, from our global network of authors to production and worldwide distribution.

CONTENTS

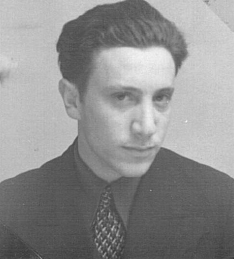

Berlin 1933

Oxford

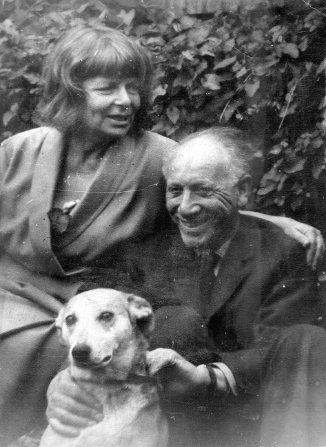

Durham, late 1950s

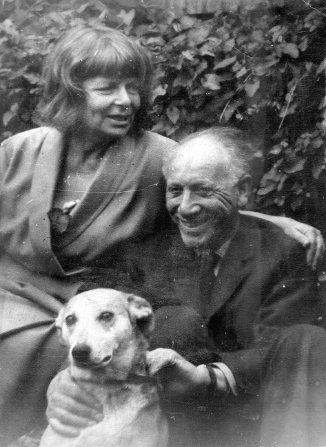

To my parents, Siegi and Lotte Moos, who gave me life.

Acknowledgements

This is a book which would never have been written, never mind finished, if it had not been for the help of a large number of people. I want to thank in particular Irene Fick for her commitment and good nature in translating so many documents from German to English and English to German without which this book would have been impossible; Richard Kirkwood for his detailed knowledge and analysis of the revolutionary left in Germany during the Weimar Republic, and for the moments of inspiration in his exploration of my fathers role in Germany and then in Britain, and Ian Birchall for his generosity in translating my fathers articles and for his astute comments on the text. My thanks also to Nick Jacobs for his translation of the biographies in Hermann Webers: Deutsche Kommunisten Biographisches handbuch 1918 bis 1945, of the men and women who pass through Siegis biography. I also want to thank the following for their interest and encouragement: Charmian Brinson, Hugh Brody, Pete Cannell, Annie Duarte-Potter, and Sue Vice. Many other people provided me with useful material and ideas, either in document form or in discussion, all of whom I acknowledge in the endnotes.

My particular thanks to Elfrieda Bruning, Hans Kohoutek and Rudi Schiffman, who has sadly died since I interviewed him. They all agreed to be interviewed aged 100 or over and gave me an invaluable insight into what it was like to be a Communist in the early 1930s in Germany. My thanks also to Dr Hans Coppi of the VVN-BdA (Vereinigung der Verfolgten des Naziregines - Bund der Antifaschistinnen und Antifaschisten (VVN-BdA e.V., Association of Victims of the Nazi-Regime) for arranging the interviews for me.

Although Chronos bore the greater part of the expense of publishing this book, it would not have been published if it were not for the generous financial support of Rudolph Moos, from the US, and Mairead Breslin Kelly, from Ireland. I suspect my father would have appreciated the historical irony that Rudolphs gift was in part a consequence of his finally reacquiring and selling land that the Nazis had taken over from Rudolphs family over seventy years ago. Maireads heart-felt gift was also a product of a shared heritage - her father and my mothers good friend had both been murdered in the USSR under Stalin. I am deeply grateful to Rudolph and Mairead for making the publication of this biography possible. Their gifts also highlight that neither Nazism nor Stalinism, both systems which blighted my parents lives, ultimately succeeded in their goals. We live to fight another day.

Finally, this book would never have been written if it had not been for my parents. My father may not always have been the easiest of dads, but I did not doubt his love for me. He encouraged in me a sense of my own uniqueness and potential, which has made writing his biography possible.

The world is a dangerous place to live in, not because of the people who are evil, but because of the people who dont do anything about it. Einstein, letter to Max Born, 1937/38

Prologue

How do I present my father? How indeed do I present myself, his daughter, in this biography?

I started to write this biography a long time after my father was dead (not uncommon, I suspect). This had the great advantage that I was not constrained by what would almost certainly have been his refusal to cooperate. My father was a complicated man with a personal and political history he preferred to keep private.

How to find out about a man who had taken his many secrets to the grave? Researching any exile, uprooted from their country of birth, is complicated. What made this even more problematic was obtaining records about my father. A combination of the allied bombing of Germany, which obliterated many records, Nazi destruction, the dispatch of KPD papers into the locked archives of the USSR and my fathers fore-sighted tendency to have hidden away under trees and floorboards - his own papers left me thin on primary material. Happily, there turned out to be useful (!) SS and Gestapo papers about Siegis time in Germany and two volumes of MI5 documents resulting from their close surveillance of my parents. And in the process of putting all this together, stories told me on those rare occasions by my father and mother came floating back into my memory.

I had left it too late to interview anybody who knew Siegi in Germany. But then who would I have interviewed anyway? As far as I could gather, my fathers comrades had mostly been murdered. The one person, who, from the letters in my fathers archives, appeared to have survived - after nine concentration camps - I failed to trace before his death, hard though I tried.

Moreover, almost everybody from my fathers immediate family had perished and the mother and daughter who did survive the camps were dead before I started this biography (one from old age, the daughter I suspect from suicide). Siegis parents had both died very young. His brother, Adolpho, had committed suicide in his early 20s. Hermann who unofficially adopted Siegi had no children of his own and died in Theriesenstadt. There is a dispersed extended family as is the way with those fleeing Nazism: Brazil, Italy, Switzerland and the US, with whom generally I have had little contact; indeed my father had not been one to keep close ties with distant relatives. Even had I started far sooner, gaining information about my father from his German days would have proved difficult. Such complexities are one reason, I suggest, why writing the stories about anti-Nazi refugees is so rare.

I was fortunate that some of my fathers articles about agit-prop had been preserved by Weber: and I thank him for allowing me to reproduce them. Siegis lyrics to accompany Wolpes music from the early 1930s also miraculously surfaced during my research. So between one form of record and another, I built up a picture. I was helped in understanding the texture of the early 1930s by interviewing three centenarians who had been in the KPD at the same time as my father, even though they did not (sadly) know him.