First published in 2014

Copyright The Commonwealth of Australia, as represented by the Australian Security Intelligence Organisation (ASIO) 2014

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without prior permission in writing from the publisher. The Australian Copyright Act 1968 (the Act) allows a maximum of one chapter or 10 per cent of this book, whichever is the greater, to be photocopied by any educational institution for its educational purposes provided that the educational institution (or body that administers it) has given a remuneration notice to the Copyright Agency (Australia) under the Act.

Allen & Unwin

83 Alexander Street

Crows Nest NSW 2065

Australia

Phone: (61 2) 8425 0100

Email:

Web: www.allenandunwin.com

Cataloguing-in-Publication details are available from the National Library of Australia

www.trove.nla.gov.au

ISBN 978 1 74331 966 6

eISBN 978 1 74343 907 4

Index by Garry Cousins

Typeset by Post Pre-press Group, Australia

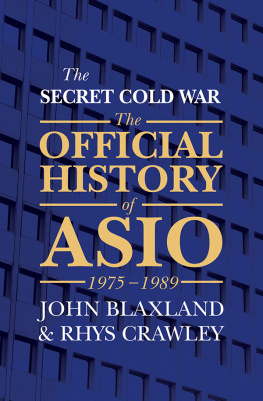

CONTENTS

Figures

Tables

The whole idea of publishing a detailed history of an intelligence organisation based on its classified files seems counterintuitive. Intelligence organisations trade in secrecy. If they reveal their sources, the sources will dry up. If they reveal their techniques their opponents will counter them. If the identities of officers are revealed they will no longer be able to operate with the freedom necessary to achieve their tasks.

Nevertheless, the appearance of histories of the British Security Service (MI5) in 2009, and the British Secret Intelligence Service (MI6) in 2010, seemed to set a precedent for an intelligence service publishing its own history. Beyond this precedent, however, there are other good reasons for publishing a history of the Australian Security Intelligence Organisation (ASIO). Through a series of historical and political circumstances, many myths or half-truths have flourished about the early decades of the Organisation. These myths damaged the Organisations standing in the Australian community, and this is unfortunate because ASIO does not exist for itself. Rather, ASIO exists to serve the nation; as a government instrumentality it ultimately needs to justify its existence to the people of Australia and both sides of Parliament, and to retain their confidence.

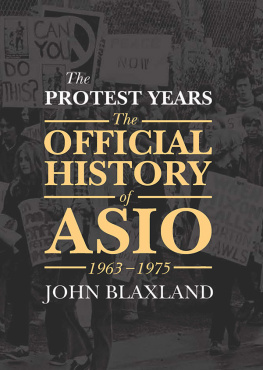

This history, based on full and unfettered access to ASIOs records, seeks therefore to tell the story of the Organisation and to dispel many of the myths about it. This particular volume explains why ASIO was formed in 1949, describes ASIOs role in the defection of the Petrovs in 1954, and ends with the expulsion of Ivan Skripov in 1963. It also describes many other activities that have never before been revealed.

The title of this volume, The Spy Catchers, has been chosen for three reasons. First, this is a history of the Organisation. It is not about Soviet espionage in Australia, the Communist Party of Australia, the Cold War, or ASIOs effect on particular groups in the community, although all of these appear prominently in the story. The focus is on the Organisation, how it dealt with certain challenges, how it changed over time, how it achieved its successes, and how at times there were shortcomings in its performance.

Second, the title is a reminder that ASIO was set up to catch spies. Evidence of Soviet espionage in the 1940s was damaging Australias national security and its relationship with its allies. ASIOs prime role was counterespionage: to deal with the immediate problem and to counter the threat in the following years. Closely allied with this role, ASIO was charged with countering subversion. In simple terms, subversion is an activity aimed at overthrowing or undermining the legitimately elected Government of Australia. In the 1950s it was undertaken by certain members of the Communist Party who rejected the accepted democratic process. ASIO was also charged with preventing sabotage to key defence facilities and national utilities. Since ASIO had evidence that members of the Communist Party had engaged in espionage on behalf of the Soviet Union, it followed that a prudent precaution was to remove members of the Communist Party from jobs where they might have access to sensitive information about national security. Hence ASIO was involved in vetting people for security clearance, but this major task was a by-product of its prime role, namely counterespionage.

Third, the title reflects the fact that the book is about ASIOs people. ASIOs officers were, and are, normal, dedicated Australians. In the 1950s they believed they were doing a job that was vital to the security of the nation. They need to be brought out of the shadows, and their efforts in the service of Australia need to be recognised.

In 2008 the Commonwealth Attorney-General approved the idea of an official history of ASIO, and the Organisation advertised for authors or institutions to tender to research and write it. It needs to be emphasised that an official history of an organisation is not the organisations view of its history and its assessment of its own achievements. Rather, it is the history of the organisation, written by an independent historian, but based primarily on the organisations own records.

The Australian National University (ANU) won the tender and the project began formally in August 2009. As the principal author I was adamant about several matters. We would not accept any direction from ASIO as to how we would tell the story, and we would write the history as we saw it, based on ASIOs records. To achieve this aim we would need complete and unrestricted access to all ASIO records relevant to the period we were researching. I am pleased to say that ASIO kept its part of this bargain to the full. We were not denied access to any file we asked for, and we found files that ASIO did not even know they had. Further, because some of the records about ASIO are held by other government departments, such as the Attorney-Generals and the departments of Defence, Immigration, Foreign Affairs and Trade, and the Prime Minister and Cabinet, ASIO asked those departments for access to relevant records. Those departments generously agreed. Finally, we were adamant that we needed to write the history at the ANU. We did not want to become part of ASIO and we needed to keep some academic distance from the Organisation.

Naturally, there are some aspects of the story we will be unable to publish for reasons of national security or international relations. But surprisingly few of these matters have been deleted from this volume.

Although it is illegal under the ASIO Act to release the names of ASIO officers, we were keen to identify as many of them as possible. When we interviewed former ASIO officers we asked them to agree to have their names revealed. Most did so. We were then able to seek permission from the Director-General of Security to release the names. We are grateful to all the former ASIO officers we interviewed and to several of them who read and commented on drafts of the history.

We wanted to be sure that if we encountered any problem we could appeal to a semi-outside body. ASIO therefore established a history advisory committee. It was chaired by the Director-General and included one of his deputies. But it also included two outsidersProfessor Geoff Gallop, a former Labor Premier of Western Australia, and Jim Carlton, a former minister in the Fraser Coalition Government. This committee did not seek to give any direction to the writing of the history, but provided valuable advice.

Next page