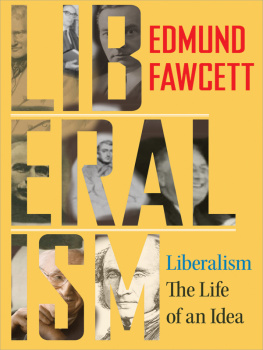

Liberalism

THE LIFE OF AN IDEA

Liberalism

THE LIFE OF AN IDEA

Edmund Fawcett

Princeton University Press

Princeton & Oxford

Copyright 2014 by Edmund Fawcett

Requests for permission to reproduce material from this work should be sent to Permissions, Princeton University Press

Published by Princeton University Press, 41 William Street, Princeton, New Jersey 08540

In the United Kingdom: Princeton University Press, 6 Oxford Street, Woodstock, Oxfordshire OX20 1TW

press.princeton.edu

JACKET ART: Row 1: Wilhelm von Humboldt; Isaiah Berlin (Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division, reproduction number LC-USZ62-112715); Walter Lippmann (Walter Lippmann Papers, Manuscripts and Archives, Yale University Library). Row 2: John Maynard Keynes, (print collection, Miriam and Ira D. Wallach Division of Art, Prints and Photographs, The New York Public Library, Astor, Lenox and Tilden Foundations); Alxis Charles Henry de Tocqueville (lithograph, 1848, by Thodore Chassriau. Rosenwald Collection, 1952.8.215. Courtesy of the National Gallery of Art, Washington); Franklin Delano Roosevelt, photograph by Harris & Ewing (Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division, reproduction number LC-DIG-hec-47235). Row 3: Friedrich von Hayek (Courtesy of the Ludwig von Mises Institute); John Stuart Mill

All Rights Reserved

LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGING-IN-PUBLICATION DATA

Fawcett, Edmund.

Liberalism : the life of an idea / Edmund Fawcett.

pages cm

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-0-691-15689-7 (cloth : alk. paper) 1. Liberalism. I. Title.

JC574.F39 2014

320.51dc23 201304736

British Library Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available

This book has been composed in Kepler Std

Printed on acid-free paper

Printed in the United States of America

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

DEDICATION

TO MARLOWE AND IN MEMORY OF HIS BROTHER, ELIAS

CONTENTS

PREFACE

This is a book about a god that succeeded, though a rather neurotic god that frets about why it has succeeded, whether it really has succeeded, and, if it has, how long success can last. It asks itself who it is and which its idols are. It worries whether it deserves its success or whether it is simply a successor, the next god in line. For one so widely worshipped, the self-doubt is startling. But this is an ungodly god that got its start by challenging other authorities, if not the notion of authority itself. It is the kind of god that tells people to obey its commands so long as they agree to. Though it is hard to picture the world without it, nobody is quite sure what it is or why it feels indispensable. The gods name is liberalism.

Not only is there no quick way to fill out the dots in Liberalism may be defined as . It is hard in many places to get the word out without meeting incomprehension or abuse. Among European anti-globalists liberal means a blind apologist of market greed. To angry American conservatives, liberals are an amoral, bleeding-heart elite. To its zippier metropolitan fans, liberalism nowadays suggests little more than letting people in boardrooms and bedrooms do as they please. Across the wider world, liberalism blurs in many minds with a Western way of life, whether envied or scorned, to be imitated or left aside.

People will tell you that liberals believe in free markets, low taxes, and limited government. Or no, that what really marks a liberal is mutual acceptance, equal respect, social concern, and standing up to bullies. You will hear that liberals are principle-spouting humbugs or dithering fence-sitters, that they are leftists, rightists, or incorrigible centrists hawking for supporters in an ever-shifting middle ground.

If, as I do, you think that liberalism is worth standing up for, then it matters to see liberalism for what it is. As that takes recognizing what kind of thing it is, here too the story threatens to stop before it starts. Liberalism, you will be told, is an ethical creed, an economic picture of society, a philosophy of politics, a capitalist rationale, a provincial Western outlook, a passing historical phase, or a timeless body of universal ideals. None of that is strictly wrong, but all of it is partial. Liberalism on this telling is a modern practice of politics. Like any practice, liberalism has a history, practitioners, and an outlook to guide them. My book involves the running story of all three.

Liberalism has no foundation myth or year of birth. Although its intellectual sources go back as far as energy or curiosity will take you, it arose as a practice of politics in the years after 1815 across the Euro-Atlantic world, but nowhere significantly before. Liberalism responded to a novel condition of society energized by capitalism and shaken by revolution in which for better or worse material and ethical change now appeared ceaseless. In that unfamiliar setting the first liberals sought fresh terms for the conduct of political life that would serve their aims and honor their ideals.

People before them had not fully imagined such an ever-shifting world. Thinkers of the eighteenth-century Enlightenment had encouraged the idea that people might understand and change society. David Hume and Immanuel Kant had called for liberty from ethical tutelage. Adam Smith had welcomed the first shoots of modern capitalism. None had experienced the true force of either. None had understood, let alone felt, a new state of affairs in which society was changing people, often at unprecedented speed and in ways nobody understood. That restless novelty, welcome in ways, bewildering in others, argues for an early nineteenth-century opening to the liberal epic that might otherwise look arbitrary and ill chosen.

Liberalism offered means to adapt law and government to productive new patterns of trade and industry, to hold together divided societies from which familiar organizing hierarchies and overarching creeds were disappearing and to foster or keep hold of standards of humanity, particularly standards for how state power and moneyed power must not mistreat or neglect people with less power. From their own distinctive viewpoints, the great nineteenth-century families of political opposition that sprang up in reaction to liberalismconservatism and socialismeach pictured their adversary as a reckless agent of disruptive change. It is nearer the truth to see the first liberals as struggling for a foothold of stability amid unprecedented upheaval. Liberalism from birth was as much a search for order as a pursuit of liberty.

Neither dynasties, presidencies, nor revolutions mark liberalisms life. Four periods, though, stand out. All were rough, but I have given them sharp dates for the sake of clarity. The first is 1830 to 1880, a time of youthful self-definition, rise to power, and large successes. From 1880 to 1945, liberalism matured and struck a historic compromise with democracy. From that compromise, hard-fought and unstable as it was, liberalism emerged in more inclusive form as democratic liberalism, better known as liberal democracy. After near-fatal failuresworld wars, political collapses, economic slumpliberal democracy in 1945 won itself another chance with the military defeat and moral ruin of its twentieth-century rival to the right, fascism. That third period of achievement and vindication, 1945 to 1989, ended in a year of triumph with the final surrender of liberal democracys twentieth-century rival to the left, Soviet Communism.

Giving liberalism life is a metaphor. Lives show unity and continuity. Liberalism, to my mind, shows both. The metaphor has its limits. Lives and stories end, which is not true of liberalism, not yet. A fourth part after 1989 notes a return of self-doubt as to what liberalism is and how long it may last. Current anxieties about liberalisms identity and fears for its future are probably overdone, though it would be smugand not liberalto sound certain on either point.

Next page