Publication in partnership with

the Shelby Cullom Davis Center

at Princeton University

Other Books in the Series

The Spaces of the Modern City: Imaginaries, Politics, and Everyday Life, edited by Kevin Kruse and Gyan Prakash

Noir Urbanisms: Dystopic Images of the Modern City, edited by Gyan Prakash

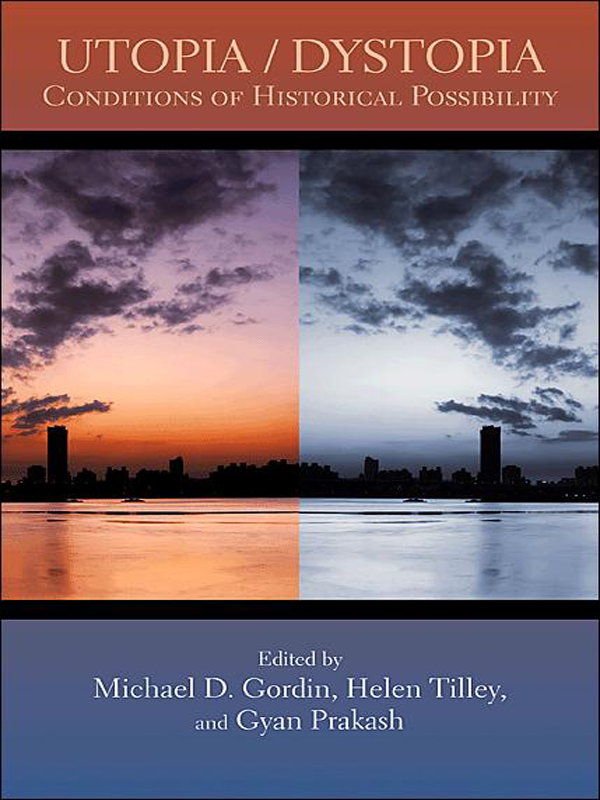

Utopia/Dystopia

CONDITIONS OF HISTORICAL POSSIBILITY

Michael D. Gordin, Helen Tilley,

and Gyan Prakash, Editors

Princeton University Press  Princeton and Oxford

Princeton and Oxford

Copyright 2010 by Princeton University Press

Published by Princeton University Press,

41 William Street, Princeton, New Jersey 08540

In the United Kingdom: Princeton University Press,

6 Oxford Street, Woodstock, Oxfordshire OX20 1TW

press.princeton.edu

All Rights Reserved

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Utopia/dystopia: conditions of historical possibility / Michael D. Gordin, Helen Tilley, and Gyan Prakash, editors.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-0-691-14697-3 (hbk.: alk. paper)ISBN 978-0-691-14698-0 (pbk.: alk. paper)

1. UtopiasHistory. 2. DystopiasHistory. I. Gordin, Michael D. II. Tilley, Helen, 1968. III. Prakash, Gyan, 1952.

HX806.U777 2010

335.02dc22 2010010267

British Library Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available

This book has been composed in Electra

Book designed by Marcella Engel Roberts

Printed on acid-free paper?

Printed in the United States of America

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Contents

PART ONE

ANIMA

1. F REDRIC J AMESON

Utopia as Method, or the Uses of the Future

2. J ENNIFER W ENZEL

Literacy and Futurity: Millennial Dreaming on the Nineteenth-Century Southern African Frontier

3. D IPESH C HAKRABARTY

Bourgeois Categories Made Global: The Utopian and Actual Lives of Historical Documents in India

4. L UISE W HITE

The Utopia of Working Phones: Rhodesian Independence and the Place of Race in Decolonization

5. T IMOTHY M ITCHELL

Hydrocarbon Utopia

PART TWO

ARTIFICE

6. J OHN K RIGE

Techno-Utopian Dreams, Techno-Political Realities: The Education of Desire for the Peaceful Atom

7. M ARCI S HORE

On Cosmopolitanism, the Avant-Garde, and a Lost Innocence of Central Europe

8. D AVID P INDER

The Breath of the Possible: Everyday Utopianism and the Street in Modernist Urbanism

9. I GAL H ALFIN

Stalinist Confessions in an Age of Terror: Messianic Times at the Leningrad Communist Universities

10. A DITYA N IGAM

The Heterotopias of Dalit Politics: Becoming-Subject and the Consumption Utopia

Introduction

M ICHAEL D. G ORDIN , H ELEN T ILLEY, AND G YAN P RAKASH

Utopia and Dystopia beyond Space and Time

U TOPIAS AND DYSTOPIAS are histories of the present. Even before we begin to explain that sentence, some readers may feel a nagging concern, for the very term utopia often sounds a little shopworn. It carries with it the trappings of an elaborate thought experiment, a kind of parlor game for intellectuals who set themselves the task of designing a future society, a perfect societyfollowing the pun on the name in Greek (no place, good place: imaginary yet positive). Projecting a better world into the future renders present-day problems more clearly. Because utopias tend to be the products of scholars and bookworms, it is not surprising that from the time of the concepts (or at least the terms) formal birth in the Renaissance, it has attracted quite a bit of academic attention. Much of this history is easily accessible, even second nature, to intellectual historians, and it traces the genealogy of ideal, planned societies as envisaged from Plato to science fiction. The appeal and the resonances are obvious and rather powerful: religious roots in paradise, political roots in socialism, economic roots in communes, and so on. Ever since Thomas More established the literary genre of utopia in his 1516 work of that title, much of historians writing on the relevance of utopia has focused on disembodied intellectual traditions, interrogating utopia as term, concept, and genre.

Dystopia, utopias twentieth-century doppelgnger, also has difficulty escaping its literary fetters. Much like utopia, dystopia has found fruitful ground to blossom in the copious expanses of science fiction, but it has also flourished in political fiction (and especially in anti-Soviet fiction), as demonstrated by the ease with which the term is applied to George Orwells 1984, Evgenii Zamiatins We, and Aldous Huxleys Brave New World. One need not be a cynic to believe that something in the notion of dystopia would be attractive and useful for historians of all stripes.

Every utopia always comes with its implied dystopia whether the dystopia of the status quo, which the utopia is engineered to address, or a dystopia found in the way this specific utopia corrupts itself in practice. Yet a dystopia does not have to be exactly a utopia inverted. In a universe subjected to increasing entropy, one finds that there are many more ways for planning to go wrong than to go right, more ways to generate dystopia than utopia. And, crucially, dystopia precisely because it is so much more common bears the aspect of lived experience. People perceive their environments as dystopic, and alas they do so with depressing frequency. Whereas utopia takes us into a future and serves to indict the present, dystopia places us directly in a dark and depressing reality, conjuring up a terrifying future if we do not recognize and treat its symptoms in the here and now. Thus the dialectic between the two imaginaries, the dream and the nightmare, also beg for inclusion together, something that traditional Begriffsgeschichte (conceptual history) would not permit almost by definition. The chief way to differentiate the two phenomena is with an eye to results, since the impulse or desire for a better future is usually present in each.

We confront, therefore, something of a puzzle, almost mathematical in nature: the opposite of dystopia seems to be utopia, but the converse does not hold. There is rather a triangle herea nexus between the perfectly planned and beneficial, the perfectly planned and unjust, and the perfectly unplanned. This volume explores the zone between these three points. It is a call to examine the historical location and conditions of utopia and dystopia not as terms or genres but as scholarly categories that promise great potential in reformulating the ways we conceptualize relationships between the past, present, and future. But what unites these three poles with each other? To our mind, the central concept that links them requires excavating the conditions of possibility even the conditions of imaginabilitybehind localized historical moments, an excavation that demands direct engagement with radical change. After all, utopias and dystopias by definition seek to alter the social order on a fundamental, systemic level. They address root causes and offer revolutionary solutions. This is what makes them recognizable. By foregrounding radical change and by considering utopia and dystopia as linked phenomena, we are able to consider just how ideas, desires, constraints, and effects interact simultaneously. Utopia, dystopia, chaos: these are not just ways of imagining the future (or the past) but can also be understood as concrete practices through which historically situated actors seek to reimagine their present and transform it into a plausible future. This is clearly

Princeton and Oxford

Princeton and Oxford