Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the Universitys objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide. Oxford is a registered trade mark of Oxford University Press in the UK and in certain other countries

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of Oxford University Press, or as expressly permitted by law, by licence or under terms agreed with the appropriate reprographics rights organization. Enquiries concerning reproduction outside the scope of the above should be sent to the Rights Department, Oxford University Press, at the address above

You must not circulate this work in any other form and you must impose this same condition on any acquirer

Published in the United States of America by Oxford University Press 198 Madison Avenue, New York, NY 10016, United States of America

Acknowledgements

Readers may recall Orwells observation that Writing a book is a horrid, exhausting struggle, like a long bout of some painful illness (Why I Write, 1946). Thankfully I have had some skilled intellectual physicians to help me through the moments when I thought I might succumb to this one. In particular, a very special thanks is due to Artur Blaim, Michael Levin, Lyman Tower Sargent, and Dan Stone, who made invaluable comments on parts of the manuscript and have greatly improved the final version. I am also grateful to Antonis Balasopoulos; Mosab Bajaber; David Bradshaw; Brentford FC and its fans for helping me see how the beautiful game is like war but so much better; Justin Champion; Janice Cullen; Zsolt Czignyik; Jos Maria Perez Fernandez; Justyna Galant; Diletta Gari; Sam Hirst; Anna Hont; Thomas Horan; Jessie Hronesova; Mark Jendrysik; Marta Komsta; Tom Moylan; Duncan Kelly; Andrew Milner; the Museum for the Political History of Russia, St Petersburg; Patrick Parrinder; Mark Preslar; Emine entrk; James Somper; Sandy Stelts at Penn State University Library; Henry Tam; Ftima Vieira; Luisa Hodgkinson and the interlibrary loan team at Royal Holloway, University of London; the London Library; the British Library; and the Orwell Archive, University College London, especially Mandy Wise. In Cambodia I am particularly grateful to the staff of the Documentation Center of Cambodia (DC-Cam), including its director, Youk Chhang, and Deputy Director, Eng Kok-Thay, and Dalin Lorn; and at the Tuol Sleng Genocide Museum, Keo Lundi. Parts of the argument have been presented at conferences or seminars at Budapest, Cambridge, Durham, Granada, Grand Forks, Krakow, Lisbon, London, Montreal, Newcastle, Oxford, Pittsburgh, Prague, Sewanee, the European University, St Petersburg, So Paulo, the University of Sussex, and Timioara. I am grateful to audiences for their feedback, and especially to members of the Utopian Studies Society (Europe) and the Society for Utopian Studies (North America). The support of the Leverhulme Trust was indispensable. I am thankful to the Salem Press for permission to reprint passages from Huxley and Bolshevism, in M. Keith Booker, ed., Aldous Huxleys Brave New World: New Critical Essays (Salem Press, 2014), pp. 91107. At Oxford University Press I am grateful to Cathryn Steele and Hollie Thomas. Elizabeth Stone was an astute and helpful copy-editor. As always, my wife and family have been supportive and endlessly patient. Finally, thanks to Christopher Duggan, whose life was cut short tragically before the book was finished, for twenty years of friendship and encouragement.

Table of Contents

We do not believe, we are afraid.

(Eskimo shaman)

[F]ear, my good friends, fear is the very basis and foundation of modern life. Fear of the much touted technology which, while it raises our standard of living, increases the probability of our violently dying. Fear of the science which takes away with one hand even more than what it so profusely gives with the other. Fear of the demonstrably fatal institutions for which, in our suicidal loyalty, we are ready to kill and die. Fear of the Great Men whom we have raised, by popular acclaim, to a power which they use, inevitably, to murder and enslave us. Fear of the War we dont want and yet do everything we can to bring about.

(Aldous Huxley, Ape and Essence, 1949)

Hell is other people.

(Jean-Paul Sartre, No Exit, 1944)

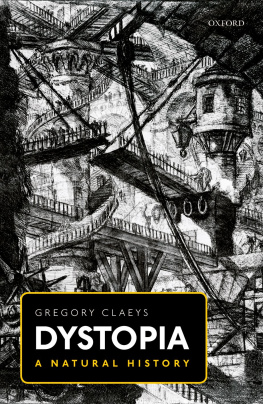

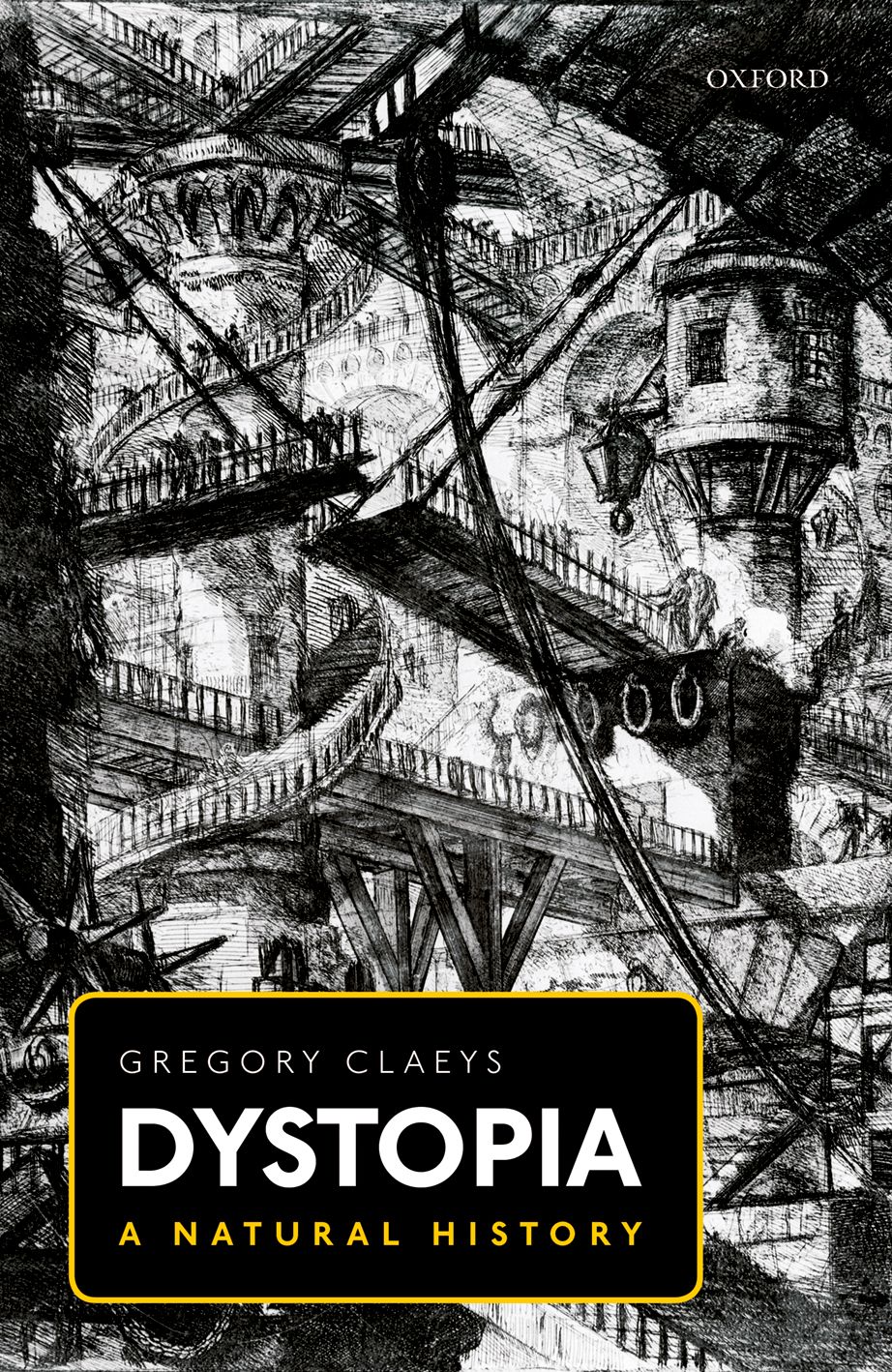

The word dystopia evokes disturbing images. We recall ancient myths of the Flood, that universal inundation induced by Divine wrath, and of the Apocalypse of Judgement Day. We see landscapes defined by ruin, death, destruction. We see swollen corpses, derelict buildings, submerged monuments, decaying cities, wastelands, the rubble of collapsed civilizations. We see cataclysm, war, lawlessness, disorder, pain, and suffering. Mountains of uncollected rubbish tower over abandoned cars. Flies buzz over animal carcases. Useless banknotes flutter in the wind. Our symbols of species power stand starkly useless: decay is universal.

Or: we see miles of barbed wire broken by guard towers topped with machine guns and searchlights; the deathstrips and minefields; the snarling guard dogs; the eyes of the haunted gaunt faces of the skeletal half-dead staring out of deep sockets aghast at their ill-deserved fate; corpses piled up like logs, grimacing skulls frozen in the last moment of madness.

Or: grim streets dominated by giant portraits of the Leader witness lengthy queues for food of weary ill-clad workers as revolutionary announcements of norms exceeded in the production plan blare out from a thousand loudspeakers.

Or: a proliferation of mushroom clouds indicates humanitys end through nuclear war.

Or: roaring planes fly overhead dropping bombs which burst among us, as men in gas masks stride over mangled corpses to stick bayonets into us or incinerate us with flamethrowers.

Or: human society resembles an ant heap in which mammoth cities are dominated by vast teeming slums and immense skyscrapers which are separated by walls from elite compounds guarded by menacing security forces.

Now the black and white newsreels give way to colour: dystopias is blood-red. Violent explosions interspersed by screams of terror deafen us and rock the earth: this is the sound of dystopia. Burning flesh, cordite, sweat, vomit, urine, excrement, rotting garbage: this is the stench of dystopia. But what really reeks is stark naked barbarism: the perfumed scents of civility are but a distant memory. We have reverted to savagery, animality, monstrosity. And then, perhaps mercifully, the end comes.