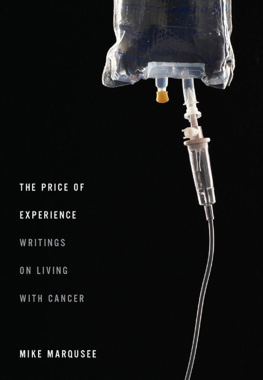

Diagnosed with multiple myeloma, a type of blood cancer, six years ago, Mike Marqusee was at first reluctant to write about such a private condition. But he came to realize that writing provided a precious continuity with his work before the disease. It also allowed him to address a variety of insidious platitudes that surround illness, often connected to the individualistic idea that the sufferer must be brave.

And so Marqusee began to write about his symptoms and feelings, the responses of friends to the news that he was ill, and the way these reflected broader attitudes. He described the political struggles occurring in the London hospital that continues to care for him, and the crisis in Britains National Health Service (NHS). Big Pharma, whose drugs keep Marqusee alive but which are sold to the NHS at extortionate prices, fell under particularly astringent scrutiny.

The observations about cancer in these pages are never trite or sentimental. Rather they are acute, impassioned, and political. And they convey important, shared truths, both personal and social, about an illness that will affect one in three people.

MIKE MARQUSEE is an American-born writer, journalist, and political activist who has lived in Britain since 1971. He is the author of numerous books including If I Am Not for Myself: Journey of an Anti-Zionist Jew, Wicked Messenger: Bob Dylan and the Sixties, Redemption Song: Muhammad Ali and the Spirit of the Sixties, Anyone but England: An Outsider Looks at English Cricket , a novel, Slow Turn , and a collection of poetry, Street Music.

ALSO BY MIKE MARQUSEE

Anyone But England: An Outsider Looks at English Cricket

War Minus the Shooting: A Journey through South Asia during Crickets World Cup

Redemption Song: Muhammad Ali and the Spirit of the Sixties

Wicked Messenger: Bob Dylan and the 1960s

If I Am Not for Myself: Journey of an Anti-Zionist Jew

Saved by a Wandering Mind (poems)

Street Music (poems)

For an archive of the authors writings

see WWW.MIKEMARQUSEE.COM

2014 Mike Marqusee

Published by OR Books, New York and London

Visit our website at www.orbooks.com

First printing 2014

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher, except brief passages for review purposes.

ISBN 978-1-939293-44-2 paperback

ISBN 978-1-939293-45-9 e-book

Text design by Bathcat Ltd. Typeset by Lapiz Digital, Chennai, India. Printed by BookMobile in the US and CPI Books Ltd in the UK.

CONTENTS

What is the price of Experience do men buy it for a song

Or wisdom for a dance in the street? No it is bought with the price

Of all that a man hath his house his wife his children

Wisdom is sold in the desolate market where none come to buy

And in the witherd field where the farmer plows for bread in vain

It is an easy thing to triumph in the summers sun

And in the vintage & to sing on the waggon loaded with corn

It is an easy thing to talk of patience to the afflicted

To speak the laws of prudence to the houseless wanderer

It is an easy thing to rejoice in the tents of prosperity:

Thus could I sing& thus rejoice, but it is not so with me!

William Blake, T HE F OUR Z OAS

AN INTRODUCTION

When I was diagnosed with multiple myeloma in 2007, I vowed to friends that I would not add to the surfeit of cancer confessionals. I had other topics to write about and surely nothing to add on this one, which was already extensively and expertly covered. Its a promise I should have known I would not be able to keep.

Reconstructing the early phases of the illness-treatment (at the level of individual experience, its impossible to disentangle one from the other) is difficult for me. But I do remember the day I first heard the diagnosis cancer.

I had been feeling pains in my chest and lower back for months and feeling ever more unwell in an all-encompassing way I couldnt explain, to myself or the doctors. The chest pains were confusing: located not in but over and around the heart. I had reached a stage where I was desperate for a diagnosis, any diagnosis (or so I thought).

When the GP phoned to ask me to come to the clinic to discuss my blood test results, I knew the news would not be good. I wasnt shocked when he explained that the test revealed a high level of something called paraproteins, indicative of a malignancy. He also observed that I looked terrible, and referred me to the nearby Homerton Hospital for urgent examination.

Before we parted he wrote paraprotein down on a slip of paper. At home, I looked it up on the Internet. The connection with multiple myeloma was prominent. I had vaguely heard of this disease, but knew absolutely nothing about it. That moment marked the beginning of what became a long and continuing process of education.

Later that afternoon, at the Homerton, the examination was thorough and therefore, in a way, reassuring. My heart and lungs were fine and my blood pressure was normal. But when they prodded, as they had to, the places in my rib-cage and in my pelvis where, I later learned, the myeloma lesions had formed, the pain was acute and I had to give it voice. A strange colloquy followed. Whenever the doctor prodded a sensitive spot, I uttered a loud involuntary Ouch! Sorry! she responded apologetically. Thats okay, I reassured her. Round and round we went. Ouch! Sorry! Thats okay! The doctors made it clear that I had a very serious illness and would have to go to the haemoncology unit at Barts for specialist treatment. But, they said, I wasnt dying from it just then, and could go home with my painkillers. Which, by this point, was all I really wanted to hear.

Throughout the day I had been wondering how and when I should tell Liz, my partner, what the last few hours had revealed. I rang her at work and said that I was at the Homerton but was okay, and Id explain it all when we met. My tone was light, even cheerful. She agreed to meet me at the hospital so that we could go home together, and when she arrived, I suggested we sit in the hospital caf, where I would fill her in on the days developments. I was smiling, as if it would be an amusing shaggy dog story. I started out by telling her the good news: there was nothing wrong with my heart or lungs. I look back and laugh at myself. Who was I kidding? Who was I trying to protect? It was a silly thing to do to Liz, who at first took my reassuring noises at face value. When I got to the cancer part, everything changed.

In the days that followed, my mood was volatile. At times I felt a strange calm and clarity. I walked through my neighbourhood streets, observed the distracted bustle of traffic and pedestrians, and was powerfully impressed with the idea that the larger pattern of life would go on without me. I felt sadness, but no panic. At other times, I was gripped by a cold terror. I walked down the same streets, observed the same things, but felt that larger pattern of life as a terrible condemnation, a standing rejection of my failed organism. As I passed groups of boisterous children, I was overwhelmed by a fear that I would somehow contaminate them, that they would be well advised to steer clear of me. About this time the young cricketer Stuart Broad was making a big impression for England in a series against India. The then-21-year-old all-rounder was strong, fit, and unabashedly confident in his own body. I couldnt stand the sight of him and had to turn away from the television. He was a picture of blooming good health and future promise, both of which I had lost and would never regain. I hated him for that. For a moment I was frightened that I wouldnt be able to watch cricket on television any morewhich for me would have been an irreparable loss.