REDEMPTION SONG

Also by Mike Marqusee

Slow Turn

Defeat from the Jaws of Victory: Inside Kinnocks Labour Party

(with Richard Heffernan)

Anyone But England: Cricket and the National Malaise

War Minus the Shooting: A Journey Through

South Asia During Crickets World Cup

Chimes of Freedom: The Politics of Bob Dylans Art

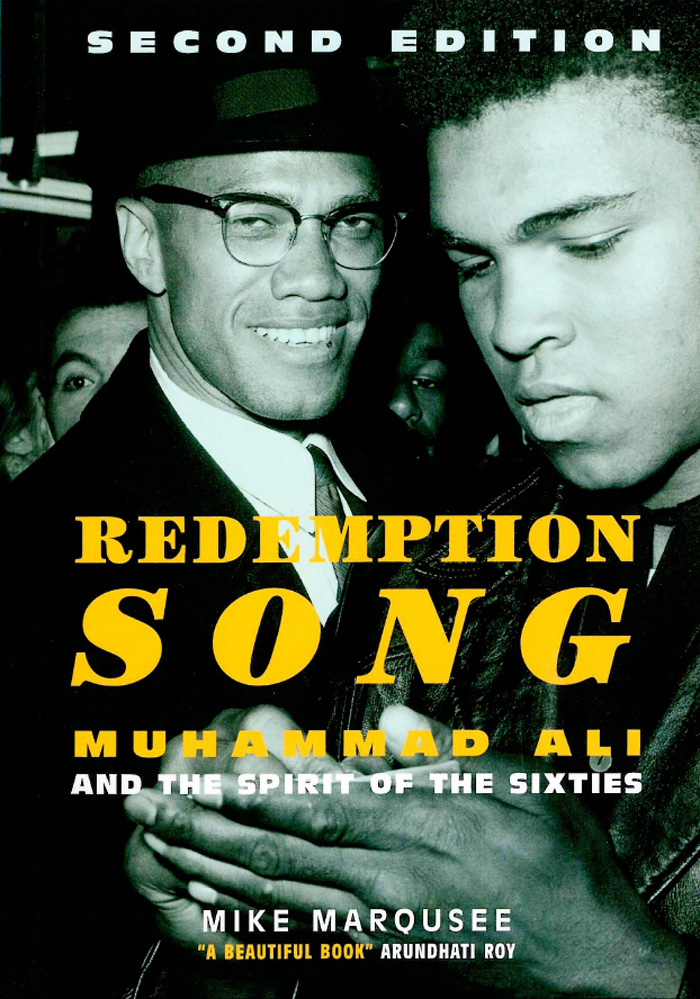

REDEMPTION SONG

MUHAMMAD ALI AND THE SPIRIT

OF THE SIXTIES

SECOND EDITION

MIKE MARQUSEE

First published by Verso 1999

Mike Marqusee 1999

Second edition first published in paperback by Verso 2005

Mike Marqusee 2005

All rights reserved

The moral rights of the author have been asserted

Verso

UK: 6 Meard Street, London W1F 0EG

US: 20 Jay Street, Suite 1010, Brooklyn, NY 11201

Verso is the imprint of New Left Books

ISBN-13: 978-1-84467-527-2 (PB)

ISBN-13: 978-1-78663-206-7 (US EBK)

ISBN-13: 978-1-78663-205-0 (UK EBK)

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

A catalog record for this book is available from the Library of Congress

Typeset by SetSystems, Saffron Walden, Essex

Printed by CPI Bath

Old pirates yes they rob I

Sold I to the merchant ships

Minutes after they took I

From the bottomless pit

But my hand was made strong

By the hand of the almighty

We forward in this generation

Triumphantly

Wont you help to sing

These songs of freedom

Cause all I ever had

Redemption songs

Redemption songs

Bob Marley

Contents

Acknowledgements

Many thanks to the following for support and stimulation: Zafaryab Ahmed, Arif Azad, Laurence Brent, Ben Carrington, Liz Davies, Steve Faulkner, John Fisher, Alan Goode, Elliott Hurwitt, Jennifer Macintosh, Jeff Marqusee, Ian McDonald, Dave Palmer, Pamela Philipose, Huw Richards, Rob Steen, Shaun Waterman. Thanks to Anthony Bah of the Ghana TUC and Niels Hooper for help digging through newspaper archives, and to Gavin Browning for photo research. Thanks also to A. Sivanandan and Hazel Waters at Race and Class, where I first published my thoughts on Ali, and to Megan Hiatt for attention to detail and care for the language (English and American). Big respect for Colin Robinson, the Greatest, publisher and friend.

Finally, this book is dedicated to my parents, Janet and John Marqusee, who served their time in the causes of peace and racial justice.

Introduction:

Ali in the Prison of the Present

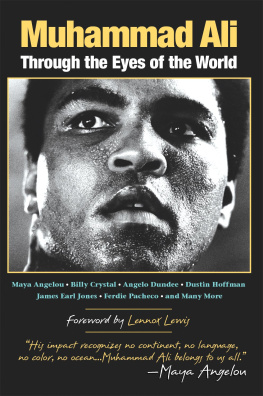

A strange fate befell Muhammad Ali in the 1990s. The man who had defied the American establishment was taken into its bosom. There he was lavished with an affection which had been strikingly absent thirty years before, when for several years he reigned unchallenged as the most reviled figure in the history of American sports.

Thanks to backstage lobbying by NBC Sports, Ali was cast as the star in the opening ceremony of the 1996 Atlanta Olympics. At the conclusion of the eighty-four-day Coca-Cola-sponsored torch relay, he raised a trembling arm to ignite the 170-foot wire fuse leading to the giant Olympic cauldron high above the stadium. In the control room, Don Mischer, creator of this high-tech, symbolically charged extravaganza, muttered into his headset, Get ready to help him. Help Ali light it. But no help was needed. The fuse was lit. The cauldron blazed into life. Corporate sponsors, television executives, spectators in the stadium and television viewers in their homes breathed a sigh of relief. Ali had triumphed yet again, this time over his own physical disabilities. Before 83,000 spectators (paying $600 per ticket) and a global television audience which the broadcasters estimated at 3 billion, Ali transcended his illness and his divisive past. The New York Times described the moment as the emotional perfect touch. To follow it up, the organizers played the famous final peroration from Martin Luther Kings speech to the 1963 March on Washington. For Atlanta columnist Dave Kindred, the whole spectacle invoked the world King spoke of on a day a generation ago. Kings one-time aide, former Atlanta mayor Andrew Young, was equally enraptured, describing the presence of Muhammad Ali as a symbol of the fact that whether were Hindu, Muslim, Catholic or Jew, were all working together.

However, not everyone was at ease with all the symbolic elements of this modern sporting and commercial rite. Outside the stadium, another former colleague of Kings, Hosea Williams, led a small protest against the Georgia state flag, which incorporates the stars and bars of the Confederacy, fluttering over a tournament ostensibly predicated on the principles of human equality. It was because of the gap between Olympic ideals and American realities that, thirty-six years earlier, Cassius Clay had flung his gold medal into the Ohio River. And as if to complete this chain of symbolic transfigurations, at half-time during the 1996 Olympic basketball final, with the Dream Team once again confirming American supremacy in the one sport entirely originated in America, Ali was presented with a replacement gold medal by the Olympic boss and former Francoist, Juan Antonio Samaranch.

Alis Olympic cameo sparked what USA Today called a renaissance for the Greatest. Sports Illustrated put him on its cover for a record-breaking thirty-fourth time. When We Were Kings, the long-delayed documentary account of his 1974 Rumble in the Jungle with George Foreman, at last reached the screens, introduced a new mass audience to the glories of Ali in his heyday and won him a share in an Oscar-night accolade. It was even rumored that Ali would be nominated for a Nobel Peace Prize in recognition of his humanitarian efforts. A wave of magazine profiles, television programs, videos and books renewed (and reinterpreted) his fame. Endorsement deals flooded in$10 million worth in a year. It says a great deal about boxing and about Ali himself that twenty years after his retirement he remained the only boxer able to attract the kind of corporate affiliations routinely offered to stars from basketball, baseball, football or track and field.

Yet during most of his boxing career, the man now being hailed as an American hero was far more popular abroad than at home. This genial nineties icon of harmony and goodwill had flaunted a religion that spurned racial integration and repudiated America as a decadent wilderness. In the name of wider and higher loyalties he refused to serve America in time of war and as a result was threatened with prison, barred from practicing his trade, harassed by his government and condemned by his countrys media. At the same time, the very actions that so enraged the defenders of Americanism made Ali a symbol of anti-American defiance and the quest for autonomy across much of Africa, Asia, Latin America and Europe.

Like Martin Luther King or even Malcolm Xtwo other sixties icons with whom Ali enjoyed more than a passing acquaintanceAli has had his political teeth extracted. Its not surprising. When an icon accumulates as many devotees as Ali has, when it emits such a numinous glow, it becomes irresistible to capitalism. Was there a better figure to help NBC, Coca-Cola and the Atlanta business elite sell the global games to America, and sell America to the world?