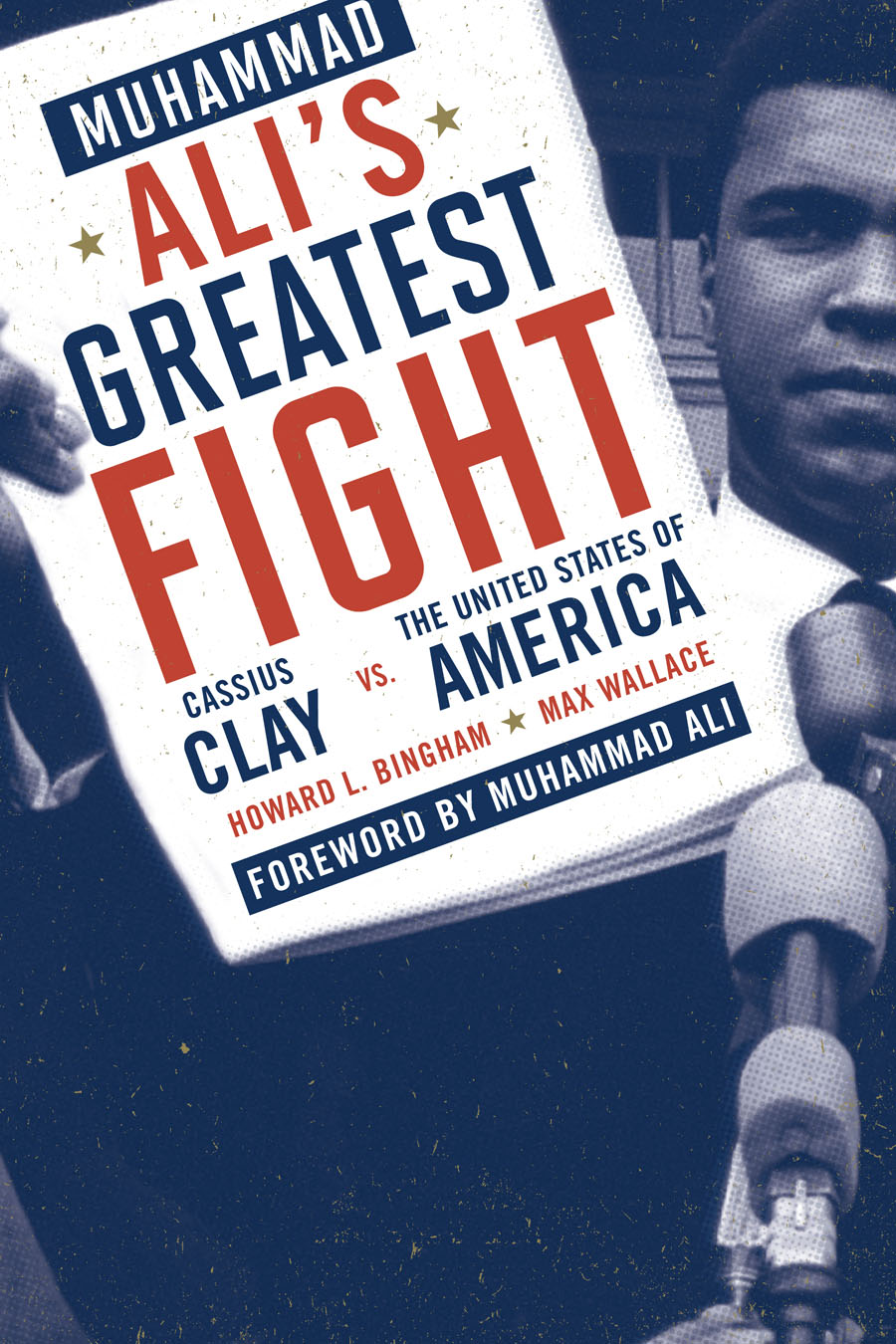

MUHAMMAD

ALIS

GREATEST FIGHT

Cassius Clay vs.

the United States of America

Published by M. Evans

An imprint of The Rowman & Littlefield Publishing Group, Inc.

4501 Forbes Boulevard, Suite 200, Lanham, Maryland 20706

www.rowman.com

10 Thornbury Road, Plymouth PL6 7PP, United Kingdom

Distributed by National Book Network

Copyright 2000 by Howard Bingham and Max Wallace

First paperback edition 2013

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, including information storage and retrieval systems, without written permission from the publisher, except by a reviewer who may quote passages in a review.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Information Available

The hardback edition of this book was previously cataloged by the Library of Congress as follows:

Bingham, Howard L.

Muhammad Alis greatest fight: Cassius Clay vs. the United States of America / by Howard Bingham and Max Wallace.

p. cm.

1. Ali, Muhammad, 1942- 2. Boxers (sports)-United States-Political activity. 3. Vietnamese Conflict, 1961-1975Conscientious objectors. 4. Boxers (Sports)United StatesBiography. I. Wallace, Max. II. Title. GV1132.A44 W24 2000

99-050269

ISBN 978-1-59077-208-9 (pbk.: alk. paper)

ISBN 978-1-59077-210-2 (electronic)

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992.

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992.

Printed in the United States of America

To all those with the courage to take a stand

FOREWORD

I NEVER THOUGHT OF MYSELF as great when I refused to go into the army. All I did was stand up for what I believed. There were people who thought the war in Vietnam was right. And those people, if they went to war, acted just as brave as I did. There were people who tried to put me in jail. Some of them were hypocrites, but others did what they thought was proper and I cant condemn them for following their consciences either. People say I made a sacrifice, risking jail and my whole career. But God told Abraham to kill his son and Abraham was willing to do it, so why shouldnt I follow what I believed? Standing up for my religion made me happy; it wasnt a sacrifice. When people got drafted and sent to Vietnam and didnt understand what the killing was about and came home with one leg and couldnt get jobs, that was a sacrifice. But I believed in what I was doing, so no matter what the government did to me, it wasnt a loss.

Some people thought I was a hero. Some people said that what I did was wrong. But everything I did was according to my conscience. I wasnt trying to be a leader. I just wanted to be free. And I made a stand all people, not just black people, should have thought about making, because it wasnt just black people being drafted. The government had a system where the rich mans son went to college, and the poor mans son went to war. Then, after the rich mans son got out of college, he did other things to keep him out of the army until he was too old to be drafted. So what I did was for me, but it was the kind of decision everyone has to make. Freedom means being able to follow your religion, but it also means carrying the responsibility to choose between right and wrong. So when the time came for me to make up my mind about going into the army, I knew people were dying in Vietnam for nothing and I knew I should live by what I thought was right. I wanted America to be America. And now the whole world knows that, so far as my own beliefs are concerned, I did what was right for me.

Muhammad Ali

CHAPTER ONE:

Louisville and the Lip

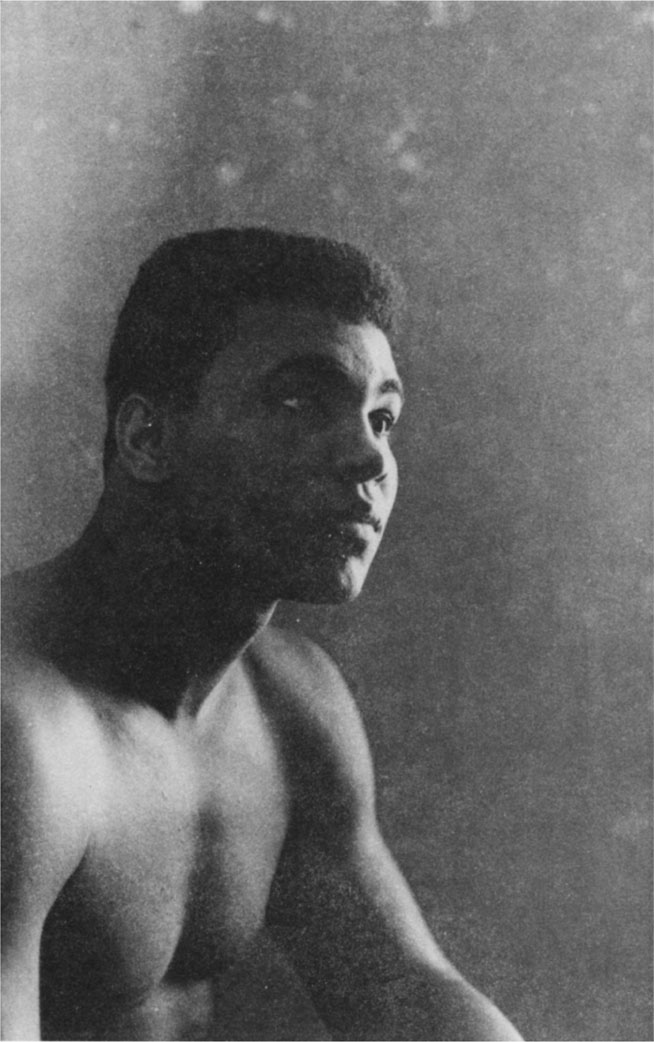

T HE GOLD MEDAL HADNT LEFT his neck since he had received it at the 1960 Summer Olympics awards ceremony the day before. He ate with it, he slept with it, he showered with it, he lay on his back so it wouldnt stab him during the night. Cassius Clay strutted around the Olympic Village in Rome showing off the medal to anybody he passed. Im the king, Im the king, he declared in the brash style that would soon become so familiar to so many. His fellow athletes from all over the world smiled and congratulated himhe had long since won them over with his infectious personality. If there had been an election for mayor of the Olympic Village, Cassius would have won in a landslide, remembers one teammate.

Heading to the cafeteria, the eighteen-year-old boxer ran into a Russian reporter who decided Clay was worth a story, despite having vanquished a Soviet contender on his way to the title. But unlike those of the hundred or so reporters to whom the new champion had already granted interviews, the Russians questions had nothing to do with boxing. He wanted to know how Clay felt as a Negro representing the United States, where he was still treated as a second-class citizen.

The U.S.A. is the best country in the world, including yours, came the response.

Undeterred, the Russian proceeded to lecture his subject about one of the most popular topics in the Soviet media during that period. He reminded the young athlete about racial inequality and segregation in America. Clay refused to rise to the bait.

We have our problems, sure, but tell your readers we got qualified people working on that, and Im not worried about the outcome.

Millions of words have been written by what journalist Robert Lipsyte calls Ali-ologists analyzing, puzzling over, and attempting to explain how the boxer involved in that three-minute exchange of patriotism could within a decade become a national pariah, labelled a traitor and almost sent to prisonall because at some point he started to worry about the outcome.

The most logical and most facile explanation is supplied by Muhammad Ali himself in his 1975 autobiography, The Greatest .

Long before even going to Rome, Clay had dreamt about the homecoming he would receive returning to Louisville, Kentucky, as Olympic champion. By the time of the Games, he had already begun to compose the doggerel that would become his trademark. On the flight across the Atlantic he penned a little poem anticipating the greeting he had fantasized about for so many years.

HOW CASSIUS TOOK ROME

BY CASSIUS CLAY JR.

To make America the greatest is my goal

So I beat the Russian, and I beat the Pole

And for the USA won the Medal of Gold.

Italians said, Youre greater than the Cassius of old.

We like your name, we like your game

So make Rome your home if you will.

I said I appreciate kind hospitality

But the USA is my country still

Cause theyre waiting to welcome me in Louisville.

The welcome, when it finally occurred, didnt disappoint. It included marching bands, red-white-and-blue streamers and, eventually, a reception by the mayor. I was deeply proud of having represented America on a world stage, Ali would later write. To me the gold medal was more than a symbol of what I had achieved for myself and my country; there was something I expected the medal to achieve for me. And during those first days of homecoming it seemed to be doing exactly that.

At the city hall reception, the mayor put his arms around the returning hometown-hero-made-good and declared, Hes our own boy, Cassius, our next world champion. Anything you want in towns yours. You hear that? Afterwards, he told reporters, If all young people could handle themselves as well as Clay does, we wouldnt have juvenile problems.

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992.

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992.