This eBook is copyright material and must not be copied, reproduced, transferred, distributed, leased, licensed or publicly performed or used in any way except as specifically permitted in writing by the publishers, as allowed under the terms and conditions under which it was purchased or as strictly permitted by applicable copyright law. Any unauthorised distribution or use of this text may be a direct infringement of the authors and publishers rights and those responsible may be liable in law accordingly.

Version 1.0

Epub ISBN 9781446492536

www.randomhouse.co.uk

Victor Bockris 1998

The right of Victor Bockris to be identified as the Author of this work has been asserted by Victor Bockris in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. All rights reserved

1 3 5 7 9 10 8 6 4 2

This edition first published in 1998 by Hutchinson

Random House (UK) Limited

20 Vauxhall Bridge Road, London SW1V 2SA

Random House Australia (Pty) Limited

20 Alfred Street, Milsons Point, Sydney,

New South Wales 2061, Australia

Random House South Africa (Pty) Limited

Endulini, 5A Jubilee Road, Parktown 2193, South Africa

A CIP record for this book is available from the British Library

ISBN 0 09 180 1958

Designed by Anthony Cohen

CONTENTS

TO ELVIS PRESLEY

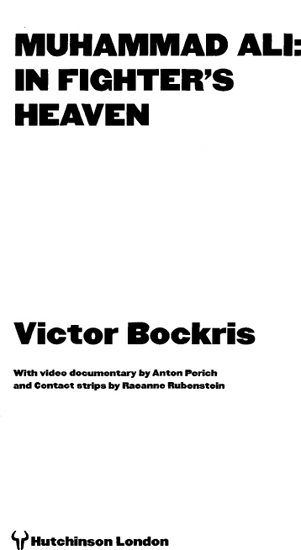

MUHAMMAD ALI: IN FIGHTERS HEAVEN

ALSO BY VICTOR BOCKRIS

With William Burroughs: A Report from the Bunker

Making Tracks: The Rise of Blondie

Uptight: The Velvet Underground Story

Warhol: The Biography

Keith Richards: The Biography

Lou Reed: The Biography

INTRODUCTION

THE FIRST ENCOUNTER

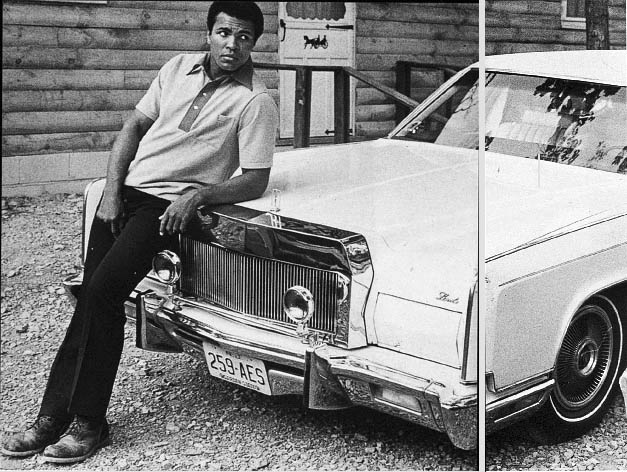

WHEN I FIRST met Muhammad Ali in the summer of 1973 he was thirty-one years old and a bundle of contradictions. While making a point of devoting his life to Black Muslim principles, he inhabited a wealthy home in a white Philadelphia suburb, and money flowed through his hands like water. He was married to his second wife Veronica, a tall, graceful black woman who adhered to his religious principles and had borne him two daughters and a son. Yet his sexual activities beyond the family fold were legend. He bought cars like Elvis; one day I would see him reclining in the back of a white stretch Lincoln limousine, the next he would be stooping into the back of a brand new green Rolls Royce to retrieve a sheaf of papers. He also owned several aeroplanes and maintained a luxurious, privately commissioned touring bus in which he and his entourage often drove to his fights.

In these details, apart from the affiliation with the Black Muslims, his life appeared little different from previous heavyweight champions. However, there was, and is, a lot more to Ali than meets the eye. Although few people knew it then, Alis plan, after regaining the heavyweight championship in Zaire in 1974, was to retire from boxing and travel around the world delivering the kinds of lectures and poems that appear later in my book.

Prior to this, some students at Oxford had passed around a petition voting Ali the next visiting professor of poetry. This was the sort of thing the press would jump on, and he would enjoy playing along with. The previous recipient of the award had been W. H. Auden. As Ali explained, They said I only had to go there twice a year to give speeches. The salary couldnt pay my laundry bills, but a boxer has never been a professor of poetry at Oxford University, so I said I would do it.

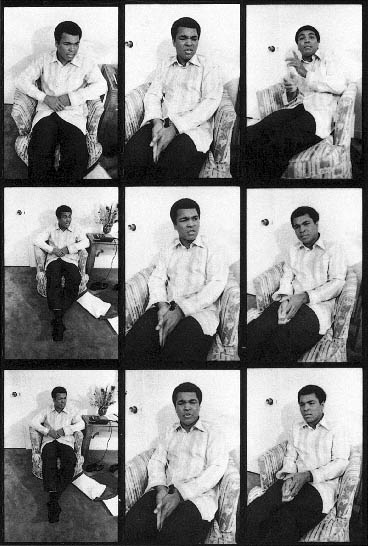

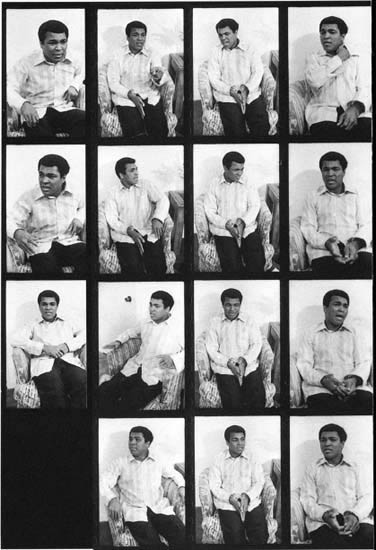

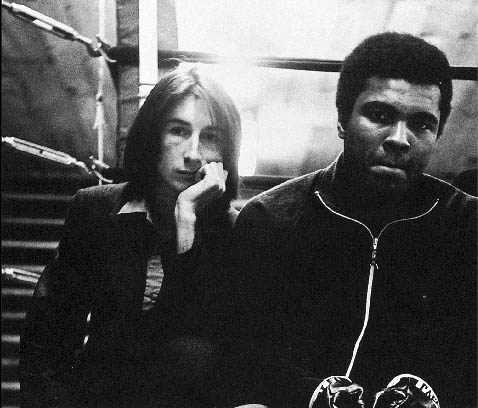

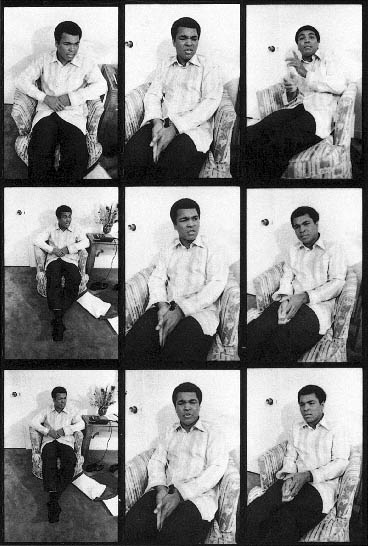

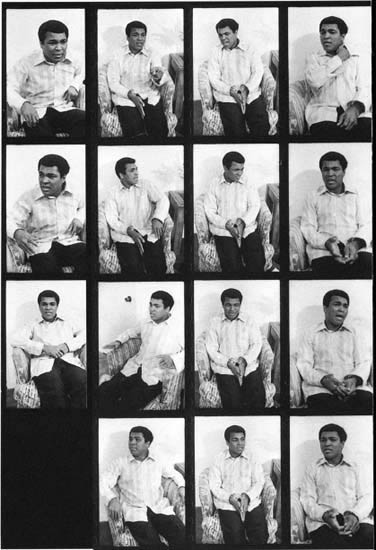

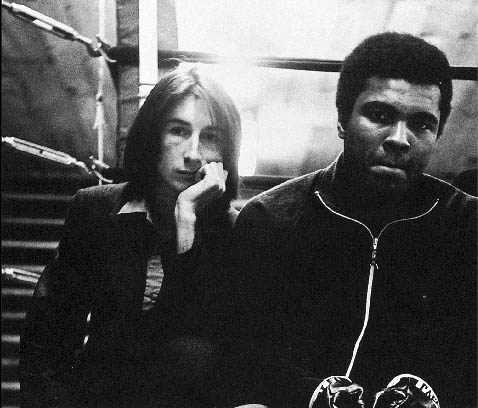

The author with Muhammad in 1973 at the time of the first interview.

At the time I was a penniless poet living in Philadelphia, trying to make a living by interviewing celebrities I thought I could learn something from for national magazines. I wasnt a committed boxing fan, but, like everyone in the world, I knew Muhammad Ali, had seen him beat Sonny Liston in 1964 and watched him battle his way back as a contender for George Foremans heavyweight crown, after having been suspended in 1967 from boxing because of his refusal to be inducted into the army during the Vietnam conflict.

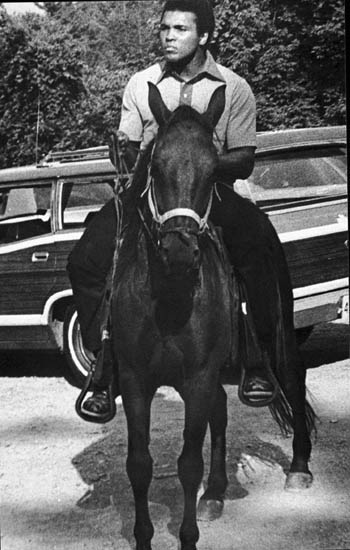

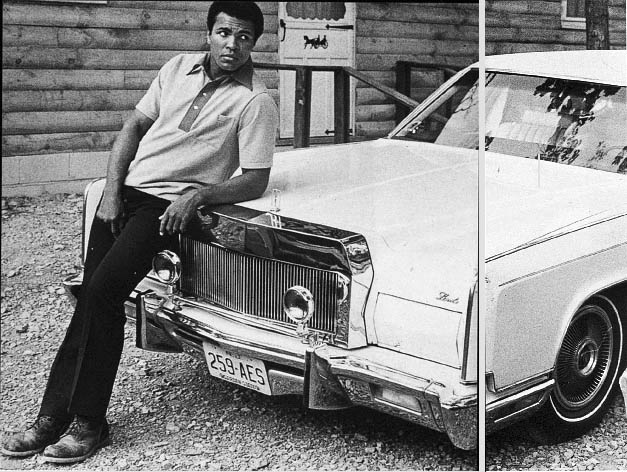

Muhammad in 1973 at Fighter's Heaven with one of his cars

When I read the piece about Ali and Oxford in a local paper, I knew I had found my subject.

Three days after I phoned him at Fighters Heaven, his training camp in Deerlake, Pennsylvania, a 1 hour drive from Philadelphia, I found myself sitting in his log-cabin kitchen underneath a sign saying Dont criticise the coffee, you may be old and weak yourself one day.

He was definitely planning to quit boxing and begin the second half of his career. They aint seen nothing yet! he assured me. They just seen a little boxing. They aint seen the real Muhammad Ali!

Ali was a quick study. He realised within the first hour of our conversation that I was somebody who might actually print what he said, because I seemed, as I was, highly amused by his scintillating talk. He turned our first one and a half hour interview into an eight hour marathon. As we were leaving the kitchen after the first round of taping, Ali shouted excitedly, Wanna go for a ride on the bus? Yes! I yelled.

One hour later, as the bus climbed back from Highway 61 up Muhammads Mountain to Fighters Heaven, Ali told me I was the young, white, college educated long hair he had been looking for, who could take his message to all the other young, white, college long hairs. During the late sixties when he was not allowed to box, Ali had made part of his much needed income lecturing at colleges just like Timothy Leary, Allen Ginsberg, Andy Warhol and the other leading counterculture figures. Now, he told me, he was getting ready to be the next black Billy Graham.

As soon as Ali beat George Foreman in the Rumble in the Jungle, as he was already calling it, and won back the world heavyweight championship, he was definitely planning to quit boxing and begin the second half of his career. They aint seen nothing yet! he assured me, popping his eyes out in a put-on bug-eyed stare. They just seen a little boxing! he shouted. They aint seen the real Muhammad Ah!

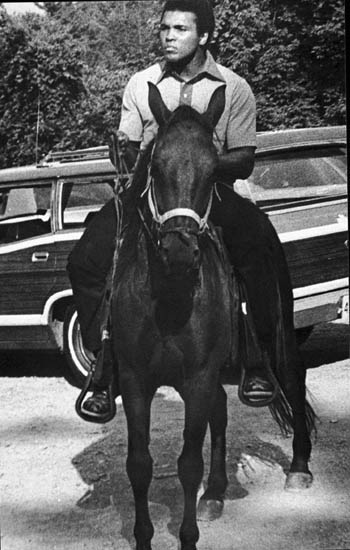

Yeah! I ride em, man. I can ride like Roy Rogers! Can I ride? You stick around a little while, you gonna see me ride!

I was invited to come and visit him at his camp whenever I wanted to. Over the next year I went up there at least ten times, taping on each occasion a conversation with Ali, in between getting to know the other people in his world.

The little book that grew out of those meetings and conversations with Ali was the brainchild of Gerard Malanga, who was an acquisitions editor at the legendary publisher Maurice Girodias (Candy, Naked Lunch, Lolita) last publishing venture, the Freeway Press. Malanga had been the first literary figure to recognise Ali as a poet in his 1963 edition of the Wagner Literary Review.

Next page