Aside from those brief chapters described as dream material,

Approaching Ali is a work of nonfiction.

Certain names and identifying details have been changed.

Copyright 2016 by Davis Miller

All rights reserved

First Edition

The chapter My Dinner with Ali was published in a much shorter form in The Best

American Sports Writing of the Century (Houghton Mifflin), The Beholders Eye: Americas

Finest Personal Journalism (Grove/Atlantic), and The Muhammad Ali Reader (Ecco Press).

The chapters The Zen of Muhammad Ali, Part One and The Zen of Muhammad Ali,

Part Two were published in a much shorter form in The Best American

Sports Writing, 1994 (Houghton Mifflin).

For information about permission to reproduce selections from this book,

write to Permissions, Liveright Publishing Corporation,

a division of W. W. Norton & Company, Inc.,

500 Fifth Avenue, New York, NY 10110

For information about special discounts for bulk purchases, please contact

W. W. Norton Special Sales at specialsales@wwnorton.com or 800-233-4830

Book design by Chris Welch

Production manager: Louise Mattarelliano

The Library of Congress has cataloged the printed edition as follows:

Names: Miller, Davis.

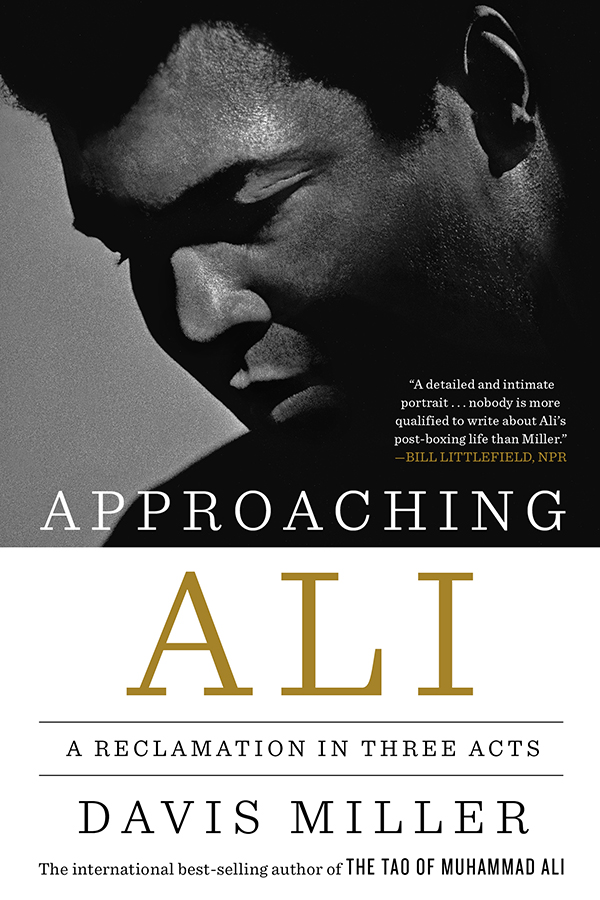

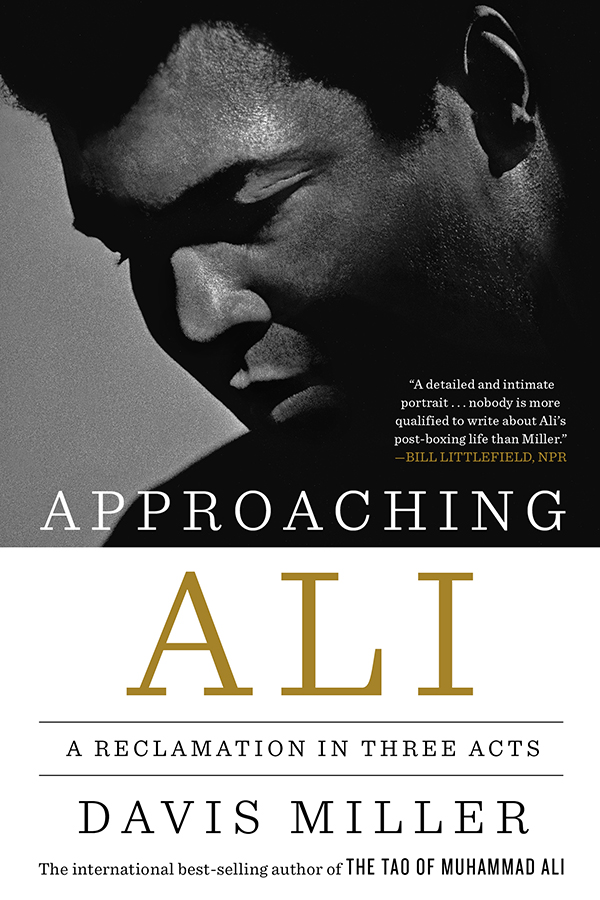

Title: Approaching Ali : a reclamation in three acts / Davis Miller.

Description: New York : Liveright Publishing Corporation, [2016]

Identifiers: LCCN 2015034856 | ISBN 9781631491153 (hardcover)

Subjects: LCSH: Ali, Muhammad, 1942 | Boxers (Sports)United StatesBiography. | African American boxers.

Classification: LCC GV1132.A44 M546 2016 | DDC 796.83092dc23

LC record available at http://lccn.loc.gov/2015034856

ISBN 978-1-63149-116-0 (e-book)

ISBN 978-1-63149-223-5 (pbk.)

Liveright Publishing Corporation

500 Fifth Avenue, New York, N.Y. 10110

www.wwnorton.com

W. W. Norton & Company Ltd.

15 Carlisle Street, London W1D 3BS

For Katherine

I am human, and nothing human is foreign to me.

TERENCE

My Dinner

with Ali

One

MARCH 31, 1988

ID BEEN WAITING FOR YEARS. When it finally happened, it wasnt what Id expected. But hes been fooling many of us for most of our lives.

When I finally got to see him, it wasnt at his farm in Michigan and I didnt have an appointment. I simply drove past his mothers house on Lambert Avenue in Louisville.

It was midafternoon on Good Friday, two days before Resurrection Day. A block-long ivory-colored Winnebago with Virginia plates was parked out front. Though he hadnt been in town much lately, I knew it was his.

How was I sure? Because I knew his patterns and style. Since 1962, when he has traveled unhurried in this country, hes preferred buses or recreational vehicles. And he owned a second farm in Virginia. The connections were obvious. Some people study faults in the earths crust or the habits of storms or of galaxies, hoping to make sense of the universe, of the world we live in, and of their own lives. Others meditate on the life and work of one social movement or man. Since I was eleven years old, I have been a Muhammad Ali scholar.

I parked my car behind his Winnebago and grabbed a few old magazines and a special stack of papers Id been storing under the front seat, waiting for the meeting with Ali that, ever since my family and Id moved to Louisville two years before, Id been certain would come. Like everyone else, I wondered in what shape Id find The Champ. Id heard about his Parkinsons disease and watched him stumble through the ropes when introduced at recent big fights. But when I thought of Ali, I remembered him as Id seen him years before, when he was luminous.

I was in my early twenties then, hoping to become a world-champion kickboxer. And I was fortunate enough to get to spar with him. I later wrote a couple of stories about the experience, the ones I had with me today hoping that hed sign.

Yes, in those days he had shone. There was an aura of light and confidence around him. He had told the world of his importance: I am the center of the universe, he howled throughout the mid-1970s, and we almost believed him. But recent magazine and newspaper articles had Ali sounding like a turtle spilled on to his back, limbs thrashing air.

It was his brother Rahaman who opened the door. He saw what I was holding under my arm, smiled an understanding smile, and said, Hes out in the Winnebago. Go knock on the door. Hell be happy to sign those for you.

Rahaman looked pretty much the way I remembered him: tall as his brother, mahogany skin, and a mustache that suggested a cross between footballer Jim Brown and a black, aging Errol Flynn. There was no indication in his voice or on his face that I would find his brother less than healthy.

I crossed the yard, climbed the three steps on the side of the Winnebago, and prepared to knock. Ali opened the door before I got the chance. Id forgotten how huge he was. His presence filled the doorway. He had to lean under the frame to see me.

I felt no nervousness. Alis face, in many ways, was as familiar to me as my fathers. His skin remained unmarked, his countenance had nearly perfect symmetry. Yet something was different: Ali was no longer the worlds prettiest man. This was only partly related to his illness; it was also because he was heavier than he needed to be. He remained handsome, even uncommonly so, but in the way of a youngish granddad who tells stories about how he could have been a movie star, if hed wanted. Alis pulchritude used to challenge us; now he looked a bit more like us, and less like an avatar sent by Allah.

Come on in, he said and waved me past. His voice had a gurgle to it, as if he needed to clear his throat. He offered a massive hand. He did not so much shake hands as he lightly placed his in mine. His touch was as gentle as a girls. His palm was cool and not callused; his fingers were the long, tapered digits of a hypnotist; his fingernails were professionally manicured; his knuckles were large and slightly swollen, as if he recently had been punching the heavy bag.

He was dressed in white, all white: new leather tennis shoes, over-the-calf cotton socks, custom-tailored linen slacks, thick short-sleeved safari-style shirt crisp with starch. I told him I thought white was a better color for him than the black he often wore those days.

He motioned for me to sit, but didnt speak. His mouth was tense at the corners; it looked like a kids who has been forced by a parent or teacher to keep it closed. He slowly lowered himself into a chair beside the window. I took a seat across from him and laid my magazines on the table between us. He immediately picked them up, produced a pen, and began signing. He asked, Whats your name? and I told him.

He continued to write without looking up. His eyes were not glazed, as Id read, but they looked tired. A wet cough rattled in his throat. His left hand trembled almost continuously. In the silence around us, I felt a need to tell him some of the things Id been wanting to say for years.

Champ, you changed my life, I said. Its true. When I was a kid, I was messed up, couldnt even talk to people. No kind of life at all.

He raised his eyes from an old healthy image of himself on a magazine cover. You made me believe I could do anything, I said.

He was watching me while I talked, not judging, just watching. I picked up a magazine from the stack in front of him. This is a story I wrote for Sports Illustrated

Next page