ILLUSTRATION CREDITS

Abbas/Magnum Photos: 7, 8, 9 below, 10 below, 11, 12, 13, 14 above, 15 above. Amanat Architect: 5 below. Bruno Barbey/Magnum Photos: 6 below. Raymond Depardon/Magnum Photos: 6 above. Jean Gaumy/Magnum Photos: 16 below. Getty Images: 1 below left and right; above right/De Agostini; 2 below, 3 below left/Gamma-Keystone; below right/Time & Life Pictures; 9 above/Michel Setboun/Gamma-Rapho; 14 centre/Alain Mingam/Gamma-Rapho; 16 centre/Jean-Claude Delmas/AFP. Thomas Hoepker/Magnum Photos: 4 below right. Inge Morath The Inge Morath Foundation/Magnum Photos: 4 above and below left. Press Association Images: 2 above, 3 above, 5 above right, 10 above, 14 below, 15 below, 16 above. Marilyn Silverstone/Magnum Photos: 5 above left. Smithsonian Institution, Washington, DC: 1 above left/Myron Bement Smith Collection, Antoin Sevruguin Photographs, Freer Gallery of Art and Arthur M. Sackler Gallery Archives, Gift of Katherine Dennis Smith.

Thank you for downloading this Simon & Schuster eBook.

Join our mailing list and get updates on new releases, deals, bonus content and other great books from Simon & Schuster.

C LICK H ERE T O S IGN U P

or visit us online to sign up at

eBookNews.SimonandSchuster.com

Contents

For Rose

Introduction

I first came to Iran in 1974, the year the price of crude oil rose fourfold and Europe switched off its power stations. After the darkness of the autobahns, I found the city of Tabriz illuminated as if for a perpetual wedding. On my first day in Tehran, the capital, I was taken on by a school teaching the English language to cadets of the Imperial Iranian Air Force. The rows of desks receded out of sight. It was Ramazan, when Muslims fast the daylight hours, and the pupils dozed on their pen-cases or glared at the wrapped sandwiches they had brought in to eat at sundown. Among those Turkoman boys, there must have been the makings of at least one military aviator, and it was I who was going to make the start on him. I was the smallest component in one of the greatest military expansions ever undertaken. The owner of the school was a brigadier general and I used to see him, in uniform in the afternoons, striking the male secretaries. At payday, the cashier, an old man with stubble on his chin, who was the generals father, took half an hour to sign my check. An Indian colleague whispered that a tip was expected. I quit.

I moved to Isfahan, the famous old city in the heart of the country. I found a job in a morning, teaching schoolgirls. I was a bad teacher, but I was an Oxford sophomore and nineteen years old. The class doubled in size and halved in fluency. My pupils cultivated feeling to a pitch, and sighed over adjectives. They made fun of me, as if I had been a bashful seminary student.

Bred up in the medieval Persian of Oxford University, I was baffled by Iranian modernity. In this famous town, with its palaces so flimsy you could blow them over with a sigh, there were military instructors from Grumman Corp. and Bell Helicopter International, with their Asian women and a screw loose from Vietnam, sobbing in hotel lobbies. I thought I had come too late to see what I had come to see, forgetting an ancient lesson: that in a year or two even this, also, would be obliterated.

I did not know, as I know now, that nations salvage what they can from the wreck of history, and the warriors of the national poet Ferdowsi were the tough guys or lutis (buggers) of the bazaar, and the lyrics of Hafez were the songs on the car radio: Black-eyed, tall and slender, Oh to win Leila! The Isfahan women rose early, buying their food from the grocery fresh each day, a clay bowl of yoghurt which they smashed after use, or those bundles of green herbs that Khomeini liked to eat, all to cook the daily lunch. For an Englishman, standing in line to buy cigarettes, it was tempting enough to stay and settle down with one of these angels, and pass his life in inconsequential fantasies. The grocer wore a double-breasted suit of wide 1930s cut, a tribal cap, and the rag-soled cotton slippers known as giveh. It was as if he had thrown off a tyrannical dress code, but only at its up and down extremities. It seemed to me that the Shah had run a blunt saw across the very grain of Iranianness.

In the cool vaults of the Isfahan bazaar, where I supplemented my wages by dealing in bad antiques, a lane would end in a chaos of smashed brick and a blinding highway, as if Mohammed Reza Pahlavi was trying to abolish something other than medieval masonry: an entire and traditional way of life, with its procession from shop to mosque to bath to shop to mosque and its interminable religious ceremonies.

Somebody, presumably the Russians, had given the Iranians a taste for assassination and vodka. Somebody else, no doubt the Americans, had given them Pepsi and ice cream. A third, perhaps the British, had taught them to love opium. Laid across that beautiful town was some personality that expressed itself in straight roads crossing at right angles, mosques turned into mere works of art, and all the frowstiness of an overtaken modernity. It was uneducated or even illiterate, violent, avaricious, in a hurry to get somewhere it never arrived. I know now that that personality was the Shahs father, Reza. Over that was another impression, not at all forceful, but cynical, melancholy, pleasure-loving, distrustful, also in a hurry. I supposed that was Mohammed Reza. I did not understand why those kings were in such a hurry but I knew that haste, as the Iranians say, is the devils work. I could see that Iran was going to hell but could not for the life of me descry what kind of hell.

James Buchan

England, 2013

CHAPTER 1

The Origins of the Pahlavi State

The foundation of injustice in the world was at first very small.

Sadi

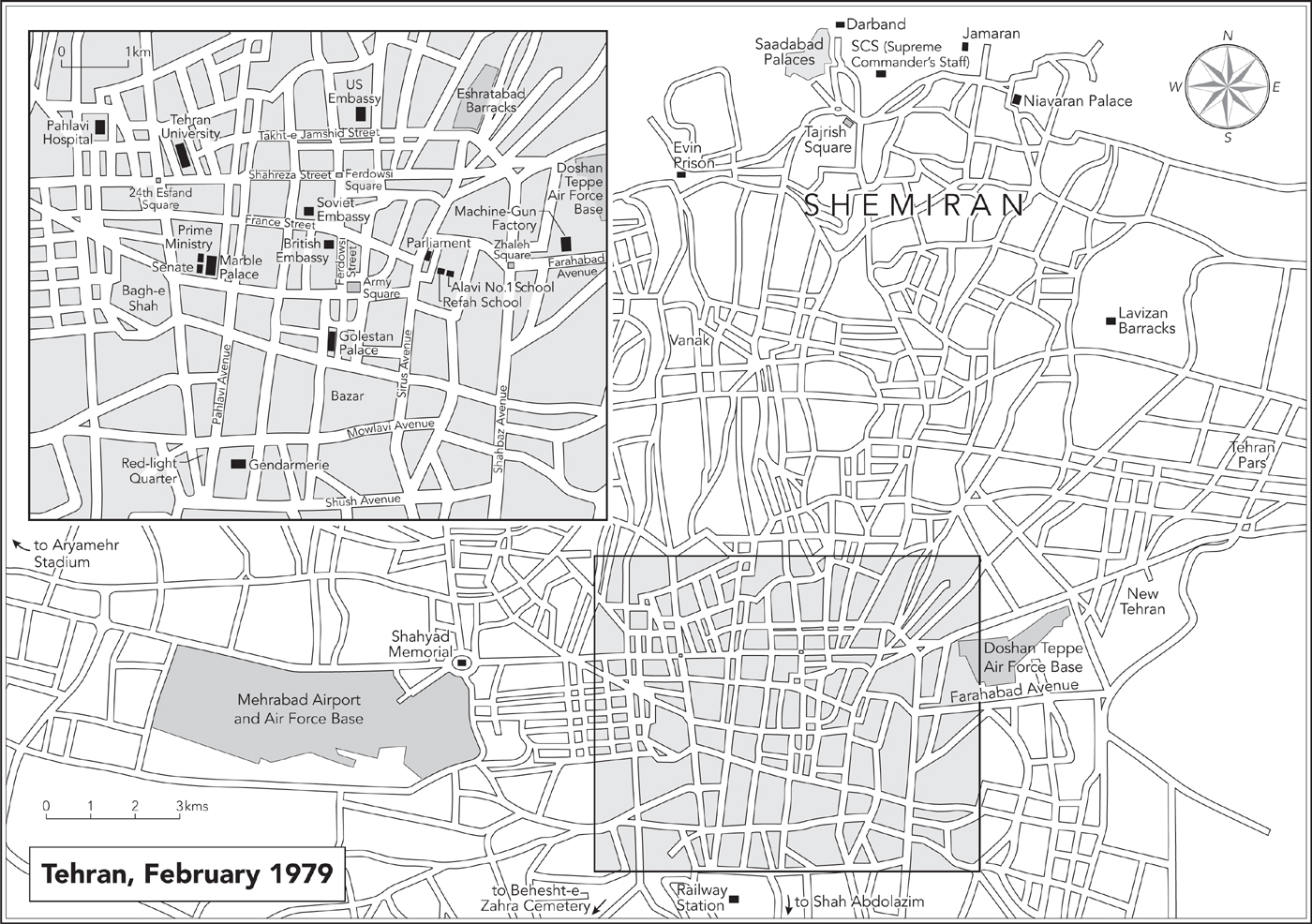

On the afternoon of Sunday, April 25, 1926, at the Golestan Palace in Tehran, a former stable lad crowned himself King of Kings. In the vaulted and mirrored hall known as the Museum, attended by cabinet ministers in cashmere robes and felt hats, civil servants, military officers in European uniforms, clergymen, cadets of the military school, and one or two European women, Reza Khan Savadkuhi of the Iranian Cossack Brigade placed on his head the new Pahlavi crown, inset with more than three thousand diamonds.

The guests were in their places by three oclock. The doors to the Museum opened and Rezas six-year-old son, Mohammed Reza, entered, dressed in miniature generals uniform of khaki, his right hand at the salute. Next came the ministers of state in two lines, carrying on red velvet cushions the regalia of the Iranian monarchy: the three crowns; the diamond-encrusted saber known as World-Conqueror, with which Nader Shah in 1739 had overrun India and sacked Delhi; the inlaid scepter; the royal gauntlet; the colossal pink diamond called the Sea of Light. Behind them, field marshals carried Naders bow, quiver, and buckler; the inlaid mace; the sword and coat-of-mail of the Safavid Shah Ismail and the sword of Shah Abbas the Great. For a country so desert and poor, and so ravaged by revolution