Con Coughlins crisp account... of the revolutions birth and Khomeinis seizure of absolute power is fast-moving yet gratifyingly detailed

TLS

This is a clear and professional account of the revolution that destroyed the Pahlavi monarchy in Iran in 1979, and of the 30 years of clerical government since then. Con Coughlin has a flair for the long-lived or permanent in Iranian history

Guardian

Coughlins book provides a warning that the West should ignore at its own peril

Tribune

The tale of the revolution and its attendant alliances, betrayals, terrors and exultation is a narrative gift and Coughlin handles it deftly... As Khomeinis Ghost shows, the strange stories of the Islamic revolution need little embellishment

Sunday Telegraph

a timely contribution to the understanding of the theocracy that has ruled Iranians for a generation

Independent

AMERICAN ALLY: TONY BLAIR AND THE WAR ON TERROR

SADDAM: HIS RISE AND FALL

For Katherine

Contents

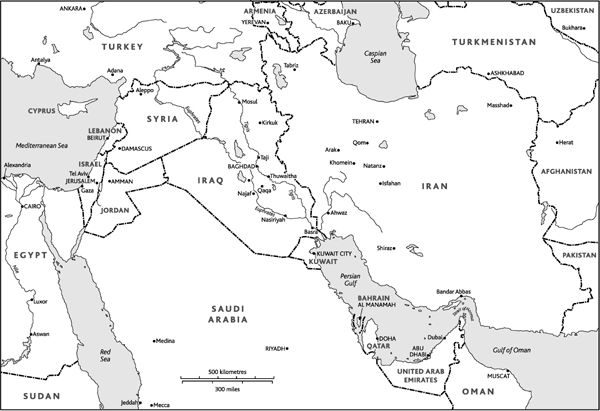

My first encounter with the forces of revolutionary Iran took place on a grey, wet morning in Beirut at the height of the Lebanese civil war in February 1984. For several days, in common with the rest of the civilian population of West Beirut, I had been forced to take shelter in a basement while rival militias battled for control of the city. The Lebanese government had all but ceased to function, and the American-led multinational peacekeeping force that had been deployed two years previously was preparing to undertake an ignominious retreat, its morale eviscerated by a sequence of deadly suicide bomb attacks. During the course of the war I had become well acquainted with the various factions fighting for supremacy, from the Christian Phalangists and their Israeli backers who dominated East Beirut, to the various Muslim, Palestinian and Druze factions that occupied the citys western and southern districts. But that morning, as I made my way tentatively through the familiar streets of West Beirut to examine the damage caused by the recent fighting, I came across an ominous new arrival on the scene groups of heavily armed young Muslim militiamen bearing the Iranian flag and posters of Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini, the founder of Irans Islamic revolution.

I knew that a small contingent of Irans Revolutionary Guards had deployed to Lebanon soon after the Israeli invasion of 1982, but had mainly confined their activities to their base in the Bekaa Valley in the east of the country. There were plenty of rumours circulating about their involvement in the suicide truck-bomb attacks against the Americans and French the previous year, but until this moment they had not made their presence felt on the war-ravaged streets of the countrys capital. Nor did they make any attempt to conceal their true allegiance when I approached them. I am a Khomeini Muslim, declared one seventeen-year-old youth who was standing beneath a picture of the Iranian leader and clutching a Kalashnikov rifle. Khomeini is our strength and our power. It later transpired that these young men were members of Hizbollah, the newly created Shia Muslim militia set up by Iran to defend the interests of Lebanons 1.5 million Shias.

Within days of their arrival on Beiruts streets the citys atmosphere took a dramatic turn for the worse. Even in the midst of a brutal conflict Beirut had managed to retain some of its pre-war glamour, when it was known as the Paris of the Levant. But within days of the arrival of pro-Khomeini militiamen young women in Western dress were roughly instructed to dress more modestly, and several bars, restaurants and hotels were attacked for refusing to dispose of their stocks of alcohol. This was the start of a campaign of intimidation that would have a dramatic impact on the city. By the end of the year, pro-Iranian militiamen had begun kidnapping Westerners as part of a deliberate campaign to drive the last remnants of Western influence from Lebanon. One morning I would be sitting in the hotel restaurant having breakfast next to Terry Anderson, the Associated Press bureau chief; hours later he had been kidnapped by pro-Khomeini gunmen, and would not be released for another six years. On another occasion I had dinner with the British journalist John McCarthy: two days later he, was abducted. Through the simple expedient of kidnapping Western citizens and holding them hostage for an indefinite period, Irans Lebanese allies succeeded in driving the remaining Westerners out of the city.

A few years later I saw another side to the devotion of Khomeinis supporters for the Islamic revolution when I accompanied a unit of Revolutionary Guards to the front line of Irans long-running war with Iraq. It was January 1987, and Iran had just launched a massive offensive on the southern front in an effort to capture Basra, Iraqs second largest city, which lies in the heart of some of the countrys largest oilfields. This was during the period when Iran was using human wave attacks against Iraqi positions, whereby thousands of young volunteers many of them teenagers would literally run across Iraqi minefields to clear the way for the main Iranian assault. I met some of these volunteers as they prepared to face certain death, and I was struck by their utter fearlessness. There is no need to be afraid, one young Iranian soldier told me as we settled down for what would probably be his last meal on earth. If I die, I know my reward will be in heaven. The following morning, when we toured the front line, the commanders of the Revolutionary Guards displayed the same courage when we came under heavy-machine-gun fire and mortar attack. At one point the Iraqi bombardment was so intense that we were forced to seek refuge in a former Iraqi trench full of dead Iraqi soldiers, so close were we to the Iraqi front line. Dont worry, you have nothing to be afraid of, one of the commanders tried to reassure me. Allah will look after us, either in this world or the next. If I die I will go straight to heaven, and why should I be afraid of going to heaven?

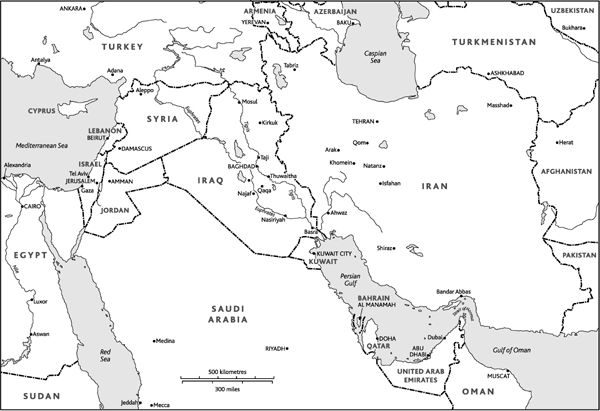

These are just some of the experiences of the past two decades that have aroused my interest in the profound effect that the Islamic revolution, launched by Ayatollah Khomeini on a largely unsuspecting Iranian nation, has had on defining the shape of the Middle East. From the radicalization of Lebanons Shia population to support for the anti-coalition insurgency in modern-day Iraq, the legacy of Khomeinis revolution is as powerful today as it was when he came to power in February 1979. At the heart of Irans revolution lies the charismatic figure of Khomeini himself, who started life as an orphan in a remote region of Persia and became one of the most influential leaders of the late twentieth century. Following his death in 1989 Khomeini bequeathed to his heirs a legacy of militant Islam that is the cause of so many of the challenges the world faces today, whether it is the potential threat posed by Irans nuclear programme or Iranian funded and trained Islamist groups in Iraq and Afghanistan, Lebanon and Gaza. In writing this book I have sought to examine and explore the influences that made Khomeini one of the towering figures of modern Islam, and the contribution that his doctrine has made to the radicalization of the Muslim world.

I have drawn on a wide range of sources, including many former supporters of the Iranian revolution who have often been the targets of assassination attempts, which they survived despite suffering severe injuries. During the past thirty years thousands of opponents of Irans Islamic revolution have been killed for their political beliefs and opinions, so it is hardly surprising that many of those I have interviewed do not want their identities revealed. Similarly, most of the senior government officials and military officers I have interviewed in Britain, America, Europe and the Middle East have requested that their names not be made public. To all of those who helped this book come to fruition I give my heartfelt thanks. I am grateful to my colleagues, past and present, at the Telegraph Media Group, firstly for giving me the opportunity to cover these momentous events and then for encouraging me to pursue my interest in the subject. I am indebted to Georgina Morley at Macmillan in London, and to Dan Halpern at Ecco in New York, for the commitment and support they have provided to this most challenging of projects, and to my redoubtable agent Gill Coleridge for making it all happen.