ONE OF THE GREAT FRUSTRATIONS of writing a work of contemporary history is that it is not possible to name many of the officials who have provided me with invaluable help, guidance, and insight. The requirements of Britains Official Secrets Act are particularly onerous in this regard, and I find it hard to believe that any of the information I have gathered in the course of my research could possibly pose a threat to national security. Many of those I have interviewed in Britain and the United States hold positions of great influence and power in their respective governments and have played a central role in the formulation of transatlantic policy in fighting the threat posed to Western security by the forces of Islamic extremism. Because of the obligations and responsibilities placed upon them by their positions, they have asked that I preserve their anonymity in the sourcing of direct quotations. While I am unable to thank them publicly for their contributions, I would nevertheless like to express my deep gratitude to them all for their helpfulness and openness, as I do to those who are in a position to be publicly identified and quoted.

Writing a book of this nature is a daunting challenge, and I am particularly grateful to Lord Powell, Lord Renwick, Lord Guthrie, Lord Butler, and Lord Robertson for laying the foundations by helping me to understand the dynamics of the transatlantic alliance from both the political and military perspectives. In London, Jonathan Powell, Downing Streets chief of staff, was invaluable in guiding me through the labyrinthine complexity of Whitehall. John Williams at the Foreign and Commonwealth Office assisted in setting up interviews with the key diplomatic players. Matthew dAncona, my former colleague at the Sunday Telegraph, elucidated some of the more obscure areas of British political discourse. Colleen Graffy, the indefatigable London-based representative for Republicans Abroad, made sure I got to see the key players in Washington, as did Devon Cross of the Pentagons Defense Policy Board and Dan Fried at the National Security Council. Gary Schmitt of the Project for the New American Century explained the origins and principles of American neoconservatism with admirable clarity, while Danielle Pletka, of the American Enterprise Institute, provided her characteristically frank take on the value of the Blair governments contribution to the war against international terrorism.

Finally, I am indebted to Dan Halpern and Emily Takoudes at Ecco for their professionalism, enthusiasm, and encouragement in guiding this book into print, and to my agents, Melanie Jackson and Gill Coleridge, for making it happen.

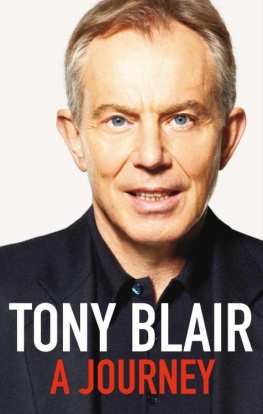

THE RESULT OF THE 1997 British election had yet to be declared, but in Washington, President Bill Clinton was excited at the prospect of the imminent victory of his young protg Tony Blair. With the exit polls suggesting a landslide victory for the New Labour leader, Clinton was pacing the Oval Office wondering when he could telephone his congratulations. The State Department urged caution, pointing out that until the result was officially declared, John Major, the Conservative leader, was still technically Britains prime minister. Blair, meanwhile, sat in the living room of his house in the northern England constituency of Sedgefield, watching the results on the television with his wife, Cherie.

Jonathan Powell, Blairs chief of staff, called Blair to pass on the message that Clinton was trying to reach him but the State Department would not yet let him. Blair was flattered, but even though all the available information pointed to the biggest election victory in Labours history, he refused to believe it until the result was official. What do they know? Blair asked Cherie as they watched the predictions of the television pollsters.

The result was finally announced several hours later, and Blair was declared the winner with the biggest majority in British postwar politics. Clinton was delighted as the extent of Blairs victory was confirmed to the White House. Clinton had struck up a close relationship with Blair, whom he regarded as a potential political ally, and members of Clintons successful 1996 campaign team had been brought to Blairs Millbank election headquarters to assist the New Labour Party. Having finally been allowed to phone Blair personally to congratulate him, Clinton issued a glowing tribute to the American press. Im looking forward to working with Prime Minister Blair, declared the American president. Hes a very exciting man, a very able man. I like him very much. Clintons enthusiastic response to Blairs victory was echoed by Sidney Blumenthal, a senior White House aide, who declared: At last the president has a little brother. Blair is the younger brother Clinton has been yearning for.

This somewhat patronizing attitude toward the new British prime minister was just some of the widespread acclaim that greeted Blairs arrival at 10 Downing Street, the official residence of Britains prime minister. It is unlikely though that anyone among the crowd that gathered outside 10 Downing Street to cheer Blairs triumph thought they were witnessing the arrival of a man who was to become one of the most important and controversial wartime leaders in British history.

The election campaign that had swept Blair and his New Labour Party to power had been fought predominantly on domestic issues, such as improving the state of Britains woeful public services. This was reflected in the selection of the pop group D:Reams song Things Can Only Get Better as New Labours official campaign anthem. The British public, or rather the ever-diminishing percentage of the electorate that actually turned out to vote, wanted better hospitals, schools, and roads. To this end, they had voted Blair into power with an impregnable 179-seat majority in the House of Commons, while the Conservatives had suffered their worst electoral defeat since the Great Reform Act of 1832. After eighteen years of Conservative rule, Britain was ready for a change in direction, and that day appeared to herald the dawn of a new era in British politics.

Tony Blair was four days short of his forty-fourth birthday when he was elected prime minister on May 2, 1997. Born in Edinburgh in 1953, Blair spent most of his childhood in the northern former coal-mining city of Durham. At fourteen, he was sent to the prestigious Fettes College boarding school and from there went to Oxford to study law.

As a young man, Blair gave his contemporaries little indication that he would one day emerge as a leading figure in world politics. To his fellow students, the long-haired Blair, who was usually dressed as a hippie, seemed like a noisy and exuberant public schoolboy rebel who steered clear of the universitys intellectual establishment. At school, Blair had played Captain Stanhope, the lead part in R. C. Sheriffs antiwar play Journeys End, and at Oxford, he continued to pursue his thespian interests, playing Matt in a college production of Bertolt Brechts