Emerge tu recuerdo de la noche en que estoy.

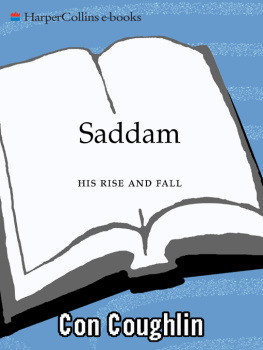

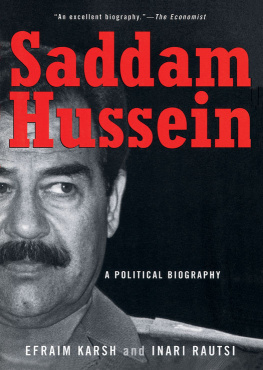

When this book was first published in the autumn of 2002, I remarked that writing a biography of Saddam Hussein was rather like trying to assemble the prosecution case against a notorious criminal gangster. Most of the key witnesses had either been murdered, or were too afraid to talk. Since I made that comment, a highly successful military campaign has been fought to overthrow Saddams regime in Iraq. Despite the coalitions success in defeating Saddam, however, it has not become any easier to chronicle the life of a man who became one of the worlds most notorious dictators.

A great deal of information was lost during the wave of looting of key government buildings that broke out immediately after the coalitions liberation of Baghdad in April 2003. And Saddams overthrow did not give his former close colleagues and associates the confidence to talk openly about his tyranny. The success of the Baathist insurgency (which Saddam himself helped to organize before the war) that was launched soon after Operation Iraqi Freedom, together with the widespread state of lawlessness that pervaded Iraq after the military campaign was concluded, meant that the same reticence that afflicted many Iraqis with inside knowledge of Saddams regime before the war continued to affect them well after the fighting had stopped. Even when the old tyrant was safely locked up in American custody, his former associates continued to live in fear that either they or their families might be subjected to revenge attacks if they spoke out of turn.

For this revised edition, which includes new material on how Saddam conducted himself during the buildup to hostilities, the war itself, and his subsequent life on the run up until his capture in December 2003, I have continued to draw on the testimony of former colleagues, Baath Party officials, and other associates of Saddamthe lucky few who managed to escape before Saddam had a chance to liquidate them. Many of them have agreedin certain cases with some reluctanceto talk openly about their experiences for the first time. Only those who were prepared to be named have been identified; in many cases, however, this has not been possible. Similarly, many of the government, diplomatic, and intelligence officialsboth serving and retiredin the United States, Europe, and the Middle East who have assisted with this undertaking have asked that their names be withheld. To everyone who enabled this project to reach fruition I offer my sincerest thanks. Naturally, I take full responsibility for the interpretations and conclusions I have reached in the course of writing this book.

I would like to express my gratitude to Linda Bedford and the librarians at the Royal Institute for International Affairs in London for their expert and efficient assistance in locating important source material, to the staff of the Telegraph library for their help in finding obscure press articles, and to Jules Amis for her unfailingly good-natured assistance.

In the interest of readability, no attempt has been made to give a scholarly transliteration of Arabic names for people or places, and the style adopted is the one generally used in British and American newspapers.

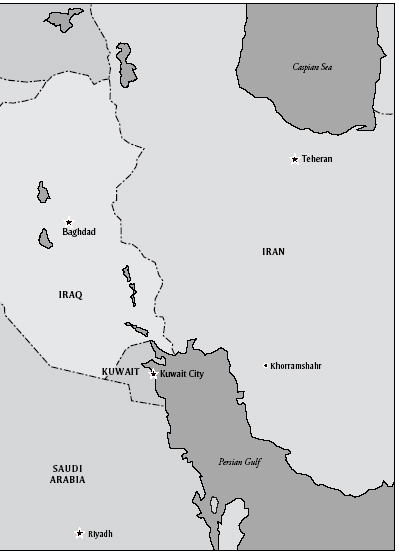

Shortly before a carefully orchestrated series of terrorist attacks devastated the eastern seaboard of the United States on the morning of September 11, 2001, several Western intelligence agencies received an intriguing report to the effect that Saddam Hussein, the president of Iraq, had placed his troops on Alert G, the highest state of military readiness Iraqi troops had seen since the 1991 Gulf War. Intelligence agents based in Iraq claimed that Saddam himself had retreated to one of his heavily fortified bunkers in the family fiefdom of Tikrit, in northern Iraq. Meanwhile his two wives, Sajida and Samira, women who in normal circumstances shunned each others company, had been moved to another of Saddams secret bunkers. The clear implication was that Saddam had retreated to Tikrit in early September 2001 because he had prior warning of the September 11 attacks, in which groups of suicidal al-Qaeda terrorists flew fully laden civilian airliners into the twin towers of New Yorks World Trade Center and the Pentagon in Washington, D.C., killing thousands of innocent civilian office workers and military personnel. A fourth team of Islamic terrorists had planned to fly their hijacked aircraft into the White House, but were prevented from doing so by the heroism of some of the passengers who tackled the hijackers, thereby causing the aircraft to crash in a field south of Pittsburgh, killing everyone on board.

In the chaotic days that followed the worlds worst terrorist atrocity, Saddam Husseins Iraq soon emerged as one of the most likely targets for retaliation. The intense secrecy and security that surrounded Saddams every move meant that it was impossible to say for sure if the intelligence reports about the Iraqi leaders actions prior to the September 11 attacks were accurate. But even though American and British intelligence were unable to find clear proof that Saddam was directly involved in the September 11 attacks, Washingtons deep-seated institutional antipathy toward the Iraqi dictator was such that President George W. Bush, in the days immediately following the atrocity, found himself having to urge restraint on his more hawkish colleagues. Bush wanted to keep the immediate focus of his response on al-Qaeda, the Islamic terrorist group led and funded by the fanatical Saudi dissident, Osama bin Laden. All the available evidence linked the hijackers directly to bin Laden. In the speech Bush made to Congress on September 20, the American president made no mention of Iraq. He spoke in general terms of fighting a war on terror, and his main demand was that the Taliban regime hand over bin Laden and his al-Qaeda accomplices, or face the consequences.

Although the main emphasis of Bushs speech was concentrated on al-Qaeda, scraps of intelligence, such as that concerning Saddams whereabouts on the morning of September 11, began to percolate in the Western intelligence community. One of the more intriguing reports was that issued by the Interior Ministry of the Czech Republic, which said that Mohammed Atta, one of the ringleaders of the September 11 bombings, had met with an Iraqi intelligence officer five months before the attacks were carried out. Atta, it was alleged, had tried to enter Prague in the summer of 2000 but had been turned away because he did not have a valid visa. The Czechs were now reporting that, having acquired the proper travel documentation, Atta had returned to Prague in April 2001, where he was said to have met with Ahmed al-Ani, an Iraqi intelligence official whom the Czech authorities were about to expel. Ani, who worked as a second consul at the Iraqi embassy in Prague, was suspected of engaging in activities beyond his diplomatic duties, the euphemism used to denote espionage. Although there was nothing to link the Iraqi agent with the September 11 bombings, the very fact that the formidable intelligence apparatus controlled by the worlds most notorious dictator might have established contact with the worlds most ruthless terrorist organization meant that Saddam might quickly find himself in the crosshairs of the Pentagons military planners. This report, like so many others, could not be taken as conclusive proof that Saddam was working with al-Qaeda. The Prague report was discounted by both the CIA and FBI, which, having conducted an exhaustive inquiry into Attas movements before 9/11, concluded that he never left the United States during the period he was supposed to have met Ani in Prague.