IN MEMORY OF

JOHN KEEGAN

(19342012)

FRIEND AND MENTOR

Prologue

Nothing in life is so exhilarating as to be shot at without result.

Winston S. Churchill, The Story of the Malakand Field Force

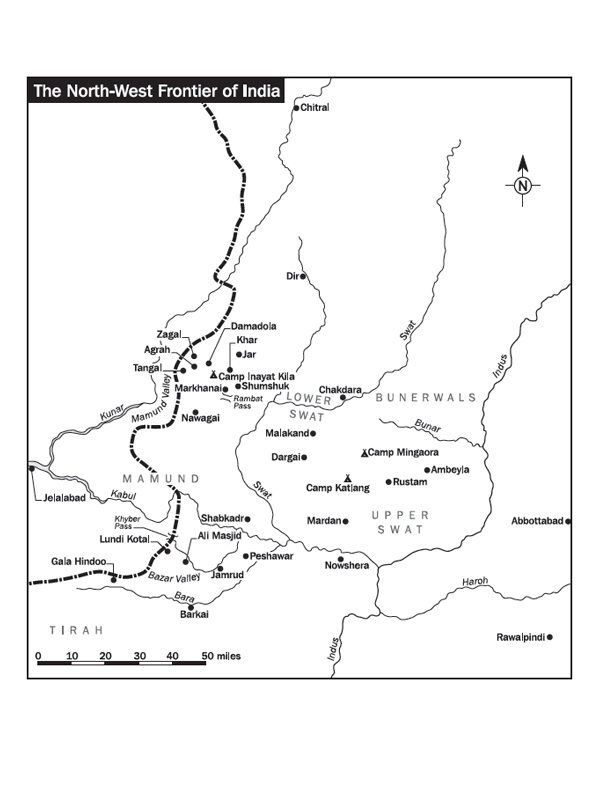

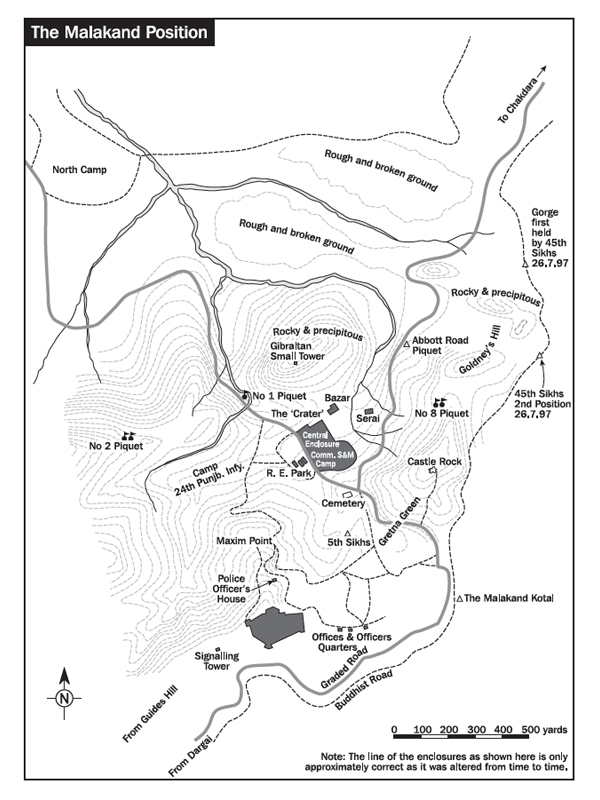

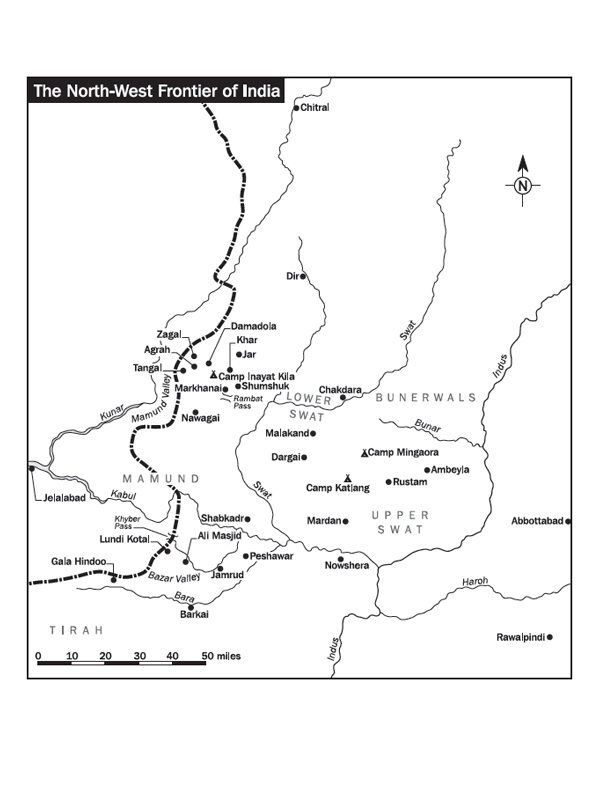

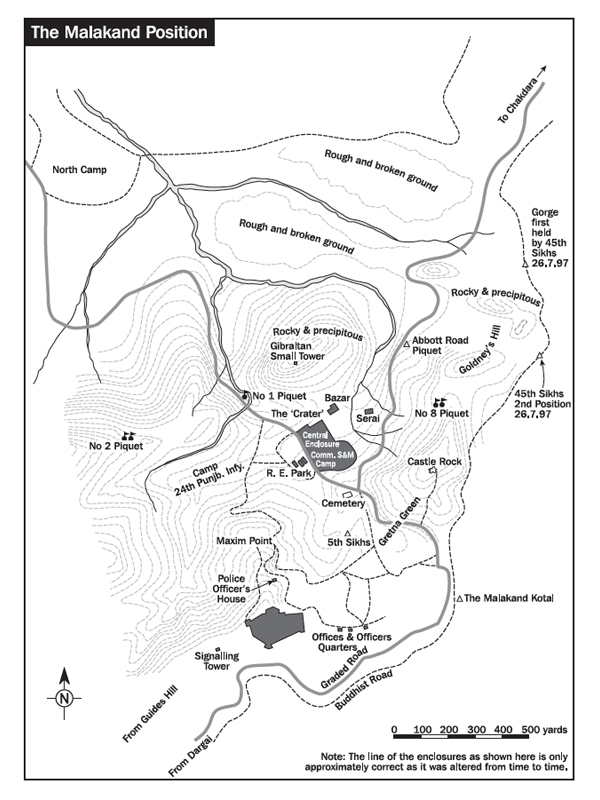

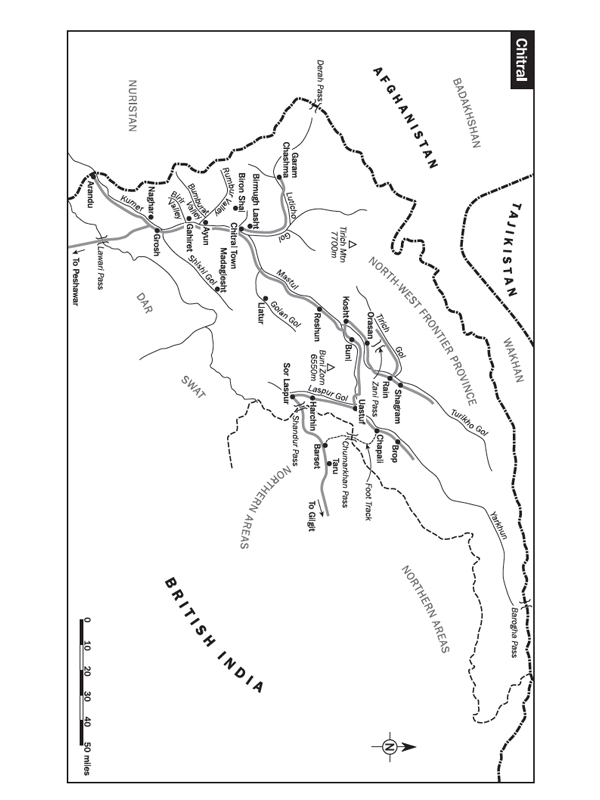

On the outskirts of the old British fort at Malakand, there is a cemetery where the bodies of young officers who died fighting for Queen and Country in a hostile outpost of the British Empire were laid to rest. Throughout the course of the nineteenth century, thousands of British soldiers lost their lives fighting the warlike tribesmen who inhabited the forbidding mountain ranges that lay between Afghanistan and the North-West Frontier of the Indian Empire. And it was here, in 1897, that Winston Churchill, as a twenty-two-year-old subaltern in the British cavalry, fought in the first of the many wars he would experience throughout the course of his long and eventful life.

For nearly six weeks Churchill risked life and limb fighting against the frontiers rebellious Pashtun tribesmen, and on several occasions came close to being killed, or at the very least suffering serious injury. He was involved in at least three sharp skirmishes, and at times the fighting was so intense that the tribesmen were able to throw rocks at him when they ran out of bullets. In all, as Churchill later boasted to his mother, he came under fire 10 complete times, and received a mention in dispatches for his bravery. Despite putting himself at risk on several occasions, Churchill survived the ordeal, but many of the other young British officers who fought at his side were not so lucky, and their remains today lie in the old British cemetery beside the fort where Churchill was based.

As a young man, Churchill did not believe he was prone to overt displays of emotion, but Browne-Claytons death hit him hard. In Churchills later account of the campaign, he simply states the facts: Lieutenant Browne-Clayton remained till the last, to watch the withdrawal, and in so doing was shot dead, the bullet severing the blood-vessels near his heart.bullets missed him by only a foot. Had they hit their target Churchill, like his friend Browne-Clayton, would lie today in some remote and forgotten grave, barely remembered. The world would have been denied one of its greatest wartime leaders, and the history of the twentieth century may well have taken a different course.

The Malakand campaign was the war that made Churchills name. Before volunteering to join the punitive expedition of the Malakand Field Force on the North-West Frontier of India, Churchill was known as the impoverished son of a maverick British politician, though he traced his descent from the Duke of Marlborough, one of Britains greatest warriors. An indifferent pupil at school who only narrowly managed at the third attempt to pass the entrance examination to the Royal Military College at Sandhurst, young Winstons prospects hardly looked promising. Nor were they improved when his father, Lord Randolph Churchill, died of syphilis shortly after Winston celebrated his twentieth birthday. Despite these disadvantages, Winston was determined from an early age to make a name for himself and pursue a career in politics. As a schoolboy, Winston had visited the Distinguished Strangers Gallery at Westminster to hear Prime Minister William Gladstone, the Grand Old Man of British politics, wind up the debate on the Home Rule Bill. The untimely death of Lord Randolph, which had cut short a political career that had once shown great promise, only strengthened his determination to succeed. No sooner had Churchill secured his commission to serve in the 4th (Queens Own) Hussars, one of Englands elite cavalry regiments, than he was thinking about how to secure the parliamentary seat that would launch his career in politics. Churchill believed that a distinguished military career was, for someone of his background and class, the perfect preparation for entering politics. Winning medals and decorations fighting for his country would enable him to beat my sword into an iron Despatch Box. For Churchill, this was the perfect

Churchills participation in the Malakand campaign laid the foundations for his future career in a number of ways. First and foremost, his decision to volunteer for duty on the Afghan border provided him with valuable combat experience. On various occasions he demonstrated courage under fire, winning the admiration of his commanding officers as well as an all-important mention in dispatches. General Sir Bindon Blood, the campaign commander, even suggested he might stand a chance of winning the much-coveted Victoria Cross. Churchills successful campaign in Malakand resulted in him taking part in several more, including the Boer War, where his dramatic escape from captivity made him a household name, helping him to win his first seat as an MP for Oldham in 1900.

Apart from the military aspects, Churchills brief interlude at Malakand was notable for other reasons. He wrote a series of articles on the conflict for the Daily Telegraph, which were well received in London, prompting the Prince of Wales to commend him for his great facility in writing. The newspaper articles, moreover, resulted in Churchill receiving a commission to publish his first book, which appeared in March 1898 under the title The Story of the Malakand Field Force: An Episode of Frontier War. The critics reviewed the book favourably, with one describing it as an extremely interesting and well-written account. Within weeks of publication, Churchill had received invitations to write biographies of his father and his great martial ancestor, the Duke of Marlborough, both of which he accomplished later in life. If all else failed, the future Nobel Prize-winning author believed he could supplement my income by writing. His experiences fighting on the North-West Frontier would feature prominently in his first autobiographical work, My Early Life, which was published more than thirty years later.

It was at Malakand that Churchill also discovered a lifelong fondness for whisky.

*

The Malakand campaign was a pivotal moment in Churchills rise to greatness, which makes it all the more surprising that this period in his life tends to be overlooked. Churchills exploits occupy a few pages of the major biographies, while Carl Foreman and Richard Attenboroughs 1972 classic film, Young Winston, devotes only the opening frames to the young subalterns hair-raising adventures fighting the fierce hill men of the Afghan border, while the rest of the narrative concentrates on his more celebrated exploits in the Sudan and the Boer War. The film opens with a shot of Churchill astride a grey horse on a hilltop on the North-West Frontier.

Whos that bloody fool on the grey? asks the colonel.

Someone who wants to be noticed, I imagine, an officer replies.

Hell be noticed hell get his bloody head blown off.

The neglect of this formative period in Churchills life is partly because, compared with his later adventures in South Africa, Churchill was fighting for only a few weeks, and his role in the campaign was peripheral. Another consideration must be that the tale of his capture and subsequent escape from a prison camp in Pretoria is more compelling, especially in view of the effect it had on his political fortunes when Churchill, like Byron after publication of

Next page