W HOLE BOOKS have been written about some of the participants in the saga of Mason and Dixons line, the Calvert and Penn families among them. You can easily find them in libraries. But many of the people (and the instruments!) who played a role in Mason and Dixons American adventure have slipped through documentary cracks in the historical record and disappeared. Or perhaps they remain lost in archives, just waiting for an adventure-seeking researcher to find them, like the information recently rediscovered about the Plumstead-Huddle house. However, records that have already come to light offer tantalizing glimpses about what happened to certain people (and instruments) who participated in the survey. Many of these glimpses raise more questions....

C HARLES MASON observed the 1769 transit of Venus, in Ireland, for the Royal Society. (After completing their survey in America, Mason and Dixon did not work together again.) He continued his astronomical work and was highly regarded for creating a set of lunar and solar tables. But he never forgot his time in America. In September 1786, Mason, Mary (his second wife), seven sons, and a daughter immigrated to Philadelphia. Less than two weeks after their arrival, he sent a note to Benjamin Franklin, informing him that he was sick and confined to bed. Sadly, Mason died less than a month later, on October 25, 1786. He is buried in an unmarked grave in Christ Church Burial Ground, not far from the tall steeple he first saw when he entered Philadelphia in 1763. Several Pennsylvania newspapers published his obituary.

J EREMIAH DIXON also observed the 1769 transit of Venus, but in Norway. Afterward, he worked as a surveyor in England. Several years later, he bought a dyehouse, which provided him with additional income. Dixon never married. He died on January 22, 1779, at the age of forty-six. The location of his grave is unknown. In his will, he left the rent and profits of the dyehouse to Margaret Bland, instructing that she use them for and towards the maintenance, education, and bringing up of her two daughters, Mary and Elizabeth. The dyehouse was to belong to Mary and Elizabeth when they reached the age of twenty-one. The relationship between Margaret, her daughters, and Jeremiah Dixon is unknown.

M OSES MCCLEAN served as a captain during the Revolutionary War. He became a prisoner of war after being captured by Indians who sided with the British. He remarried after his wife, Sarah whom Charles Mason had met died. He and his second wife moved to Ohio. Moses died in 1810.

J OHN HARLAN is reported in the Harlan family genealogy as having drowned in Brandywine Creek. His name ceases to appear in colonial records after 1768.

P HINEHAS HARLAN married his sweetheart, Elizabeth Jones, on September 24, 1766, one year after he worked as an axman on the line.

T HOMAS AND HANNAH CRESAP remained loyal Marylanders. By the mid-1740s, Thomas established a fort and trading post along the bank of the Potomac River, in the wilderness of western Maryland, and within a few years built the home Mason and Dixon visited. When George Washington was sixteen years old and participating in a frontier land survey, he spent two nights at the Cresaps home. In his journal, Washington wrote that the road to Cresaps house was I believe the Worst Road that ever was trod by Man or Beast. Cresap and his son became land speculators and founded the town of Oldtown. Hannah Cresap died before 1774. Thomas died in 1790; his grave overlooks the Potomac River. Yet his spirit of discovery lives on in the archaeological excavations on the site of Cresaps fort, where an abundance of eighteenth-century artifacts have been unearthed.

Z ENITH SECTOR: Owned by the Penn family, the sector remained in Pennsylvania. It was used to observe the 1769 transit of Venus and to survey the boundary between New York and New Jersey. After the Revolutionary War, the sector was housed in different cities, and eventually put on display in the Pennsylvania state capitol building, in Harrisburg. It was reported as destroyed when the building burned in February 1897.

T RANSIT AND EQUAL ALTITUDE INSTRUMENT: For many years, the transits whereabouts were unknown. Then, in 1912, it was found in Philadelphia underneath the floorboards in the bell tower of Independence Hall, formerly called the Pennsylvania State House, the building where Mason and Dixon sometimes met with the commissioners. How the instrument got there no one knows. It is on display in a large meeting room in the hall, possibly the same room where Mason and Dixon first unpacked it in 1763.

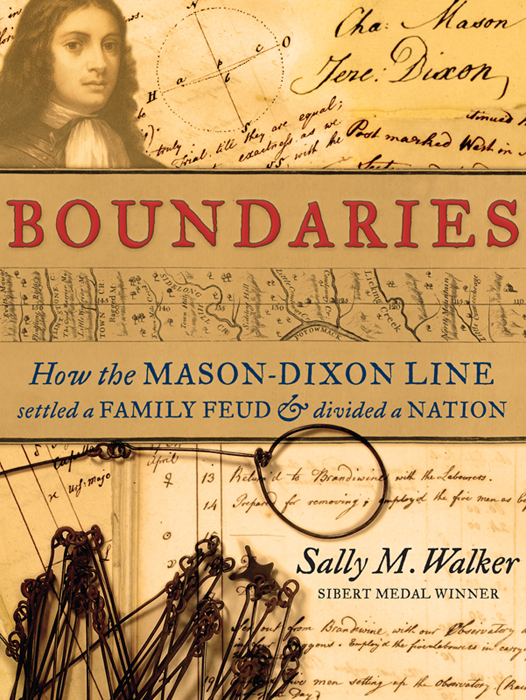

W E LIVE IN A WORLD OF BOUNDARIES.

Boundary stories are plentiful in newspapers, on television, and on the Internet. A country at war with itself divides into two separate nations. Religious boundaries lead to persecution. Cultural boundaries reflect the rich texture of diversity but also the tensions that arise when people misunderstand or misinterpret societal differences. Scientific boundaries range from the ethics of cloning to the exploration of new galaxies. All these boundaries how they change and how they dont shape our world and who we are, as individuals and as members of the world community.

The story of the Mason-Dixon Line encompasses many different boundaries, some hundreds of years old. It begins with a country and the religious persecution of its own people. It becomes a property dispute. An escalating clash across cultural boundaries is part of the tale. So is surpassing a scientific boundary to achieve a feat many people deemed impossible. The lines story slices through history and helps us understand how human perceptions and the course of a country change over time. Its the story of how a political boundary became a symbol of freedom that helped shape the history of the United States. The tale of the Mason-Dixon Line reminds us to question the boundaries that surround us. And because it does, it is a tale for all times.

In some ways, the tale of the Mason-Dixon Line is a story of twos: two feuding families, two colonies in America, two kings named Charles, and two adventuresome surveyors. Its also the tale of how nighttime skies steered daytime courses. To fully know the Mason-Dixon Lines boundaries, you must know its roots. They begin in faraway places, then twist and turn in surprising new directions. They wind through heartbreak and triumph. And sometimes, without warning, they unexpectedly veer into danger.

The Calvert family was very familiar with boundaries and their restrictions. Even before his birth, in 1579, religious boundaries controlled George Calverts life. His parents, Leonard and Alicia, were Roman Catholics. For them, worshipping publicly in England was illegal. As a little boy, George Calvert saw the Protestant authorities of Yorkshire force his father to conform to the Anglican Church. Had he refused, government jobs would have been closed to him and English society would have ostracized his family. He could even have faced imprisonment. Four years after his mothers death, George Calvert watched the same authorities similarly pressure his stepmother, who

Next page