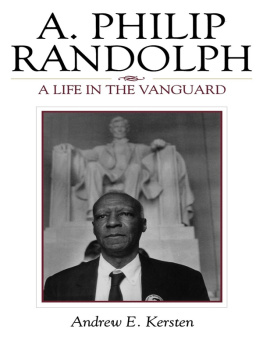

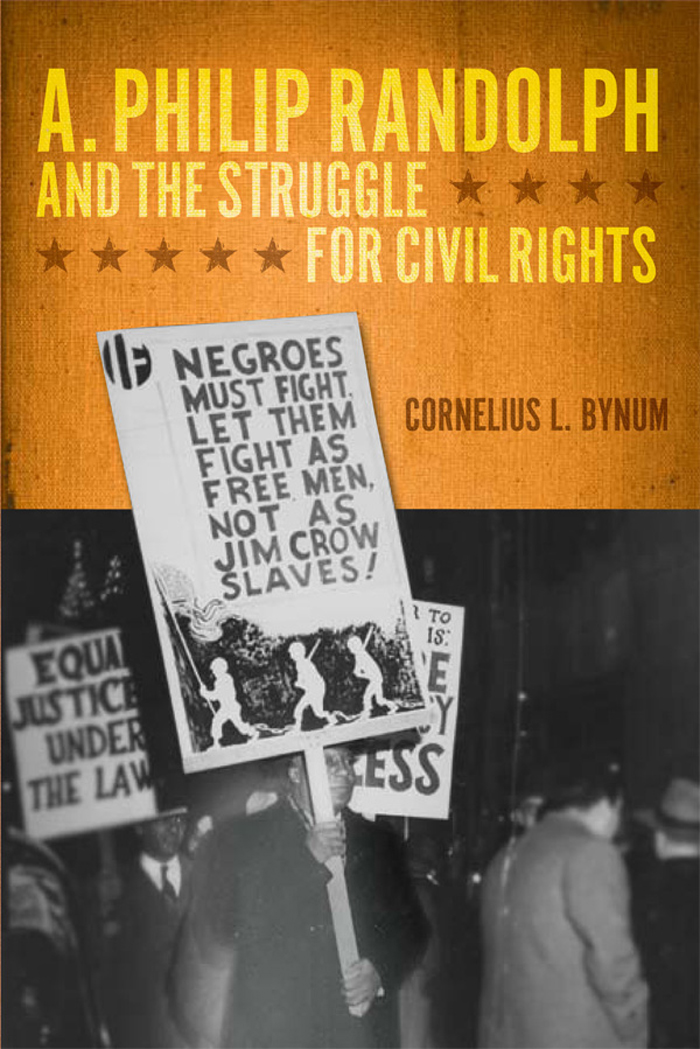

A. Philip Randolph and the Struggle for Civil Rights

THE NEW BLACK STUDIES SERIES

Edited by Darlene Clark Hine and Dwight A. McBride

A list of books in the series appears at the end of this book.

A. Philip Randolph and the Struggle for Civil Rights

CORNELIUS L. BYNUM

UNIVERSITY OF ILLINOIS PRESS

Urbana, Chicago, and Springfield

2010 by the Board of Trustees

of the University of Illinois

All rights reserved

Manufactured in the United States of America

1 2 3 4 5 c p 5 4 3 2 1

This book is printed on acid-free paper.

This book is printed on acid-free paper.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Bynum, Cornelius L.

A. Philip Randolph and the struggle for civil rights / Cornelius L. Bynum.

p. cm. (New Black studies series)

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-0-252-03575-3 (cloth : alk. paper)

ISBN 978-0-252-07764-7 (pbk. : alk. paper)

1. Randolph, A. Philip (Asa Philip), 18891979. 2. Civil rights workersUnited StatesBiography. 3. Civil rights movementsUnited StatesHistory20th century. 4. African AmericansCivil rightsHistory20th century. 5. United StatesRace relations. I. Title.

E185.97.R27B97 2011

323.092dc22 2010024822

[B]

Contents

Acknowledgments

I would have never completed this project without the assistance, guidance, and support of several different people. The dissertation that yielded this book was directed with great patience by Olivier Zunz, Commonwealth Professor of History at the University of Virginia. His guidance and demanding attention to detail were central to the development of the core ideas at the heart of this project. In the intervening years he has continued to provide invaluable advice and support. My colleagues in the History Department at Purdue University have been equally important in the development of this book. In big and small ways, they have been instrumental in my development as a scholar and writer. In particular, I would like to thank my department head, R. Douglas Hurt, and Randy Roberts, Susan Curtis, Robert May, Frank Lambert, and Nancy Gabin, each of whom read my work and provided critical feedback that greatly improved the final product.

I would also like to acknowledge the invaluable assistance and professionalism of the library staff at the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, the Newberry Library, and the Library of Congress Manuscripts Division. In particular, I would like to thank Andre Elizee and Steven Full-wood for their willingness to guide me through the Schomburg collections. There are any number of vital documents that I would have overlooked or completely missed without their thoughtful suggestions and encouragement. The staff at the Newberry was equally gracious in guiding me through the Pullman Company collection. And the staff at the Library of Congress efficiently steered me though the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People and the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters collections. In each case, the librarians that I encountered were cheerful and helpful and made some of the more tedious moments in my research a bit more pleasant.

Lastly, I would like to thank my wife, Mia. I cannot express what your love, support, and encouragement have meant to me. From the moment we met in graduate school, you have been a close confidant, steadfast friend, and companion, and there is simply no way for me to express my gratitude for all that you have done to support and encourage me.

Introduction

When nearly a quarter of a million people, black and white, gathered on the National Mall in late August 1963, they brought to life the signature moment of A. Philip Randolphs long career. Having threatened such a demonstration in 1941 to protest employment discrimination during the Second World War, Randolph was happy to see his idea for a march on Washington resurrected as a mass demonstration of support for President John F. Kennedys proposed civil rights bill. Indeed, in the aftermath of the civil rights campaign in Birmingham, Alabama, where high-compression water hoses and police dogs shocked the conscience of the nation, the time seemed ripe to push for such legislation. As the crowd gathered and made its way from the Washington Monument to the steps of the Lincoln Memorial, chants of pass that bill! ushered forth, and the protest anthem We Shall Overcome gave voice to the undeniable spirit of common purpose that suffused the day.

However, few of those that participated in the march were aware of the building behind-the-scenes drama that threatened to mar the demonstration. John Lewis of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) planned to deliver a speech criticizing the Kennedy administration for its lack of civil rights enforcement in the South and calling the presidents proposed civil rights bill too little and too late. In the months and weeks leading up to the march, organizers had worked tirelessly to allay government concerns about rabble rousing and potential violence. For some, Lewiss remarks threatened to stir up the frustrations that brought so many to the nations capital. When Bayard Rustin, one of the principal orchestrators of the march, asked him to change his remarks, Lewis adamantly refused. The opening speeches were well underway

Both march participants and historians of the era typically view the 1963 March on Washington as a triumphant moment for the civil rights movement. It was an equally triumphant moment for A. Philip Randolph. Throughout his career he had sought out mechanisms for illustrating the wide gulf between the principles of freedom and justice and the unfulfilled aspirations of the disempowered and disfranchised. His search led him to profound conclusions about the nature of genuine social justice, the interrelated character of issues of race and class, the effectiveness of interest group politics for racial minorities, and mass direct action. Though spearheaded primarily by others who set out to galvanize support for Kennedys civil rights bill, the 1963 march ultimately drew on Randolphs ideas in each of these areas to move the nation toward fulfilling its democratic promises for all. For Randolph, who remained a vocal advocate for civil rights up to his death in May 1979, the March on Washington was a culminating achievement that succinctly employed all the various aspects of his social, political, and economic thinking. As such, it was a fitting capstone to a life devoted to social justice.

In the years between the end of the First World War and the Supreme Courts 1954 Brown v. Board of Education decision, A. Philip Randolph organized the nations first all-black trade union, forced the American labor movement to take a hard look at its racial policies and practices, and secured two separate executive ordersone banning workplace discrimination in war industry jobs and the other desegregating the U.S. armed forces. Over the course of Randolphs long career as a socialist, journal editor, labor organizer, and civil rights activist, the theories he formulated became the primary basis of the civil rights protest movement of the 1950s and 1960s. His views on social justice, race and class, racial minorities and interest group politics, and mass direct action largely grew out of his overall life experiences. This study endeavors to understand how the forces that shaped Randolphs life also shaped his conception of race, class, and African Americans struggle for equal justice.

When Randolph arrived in Harlem in 1911, it marked the beginning of a remarkable personal journey that influenced key events of the interwar years and beyond. In scrutinizing his novel understanding of the intersection of race and class, two movements that have often been at odds with each other, I attempt to present an analytical intellectual history that uses biography to illuminate the origins and evolution of central aspects of Randolphs thought and activism; I examine his contributions to the problems of race, class, civil rights, and the labor movement by connecting his unfolding ideas to specific influences and experiences in his life. Most decidedly not a straightforward biography, this book examines the development of Randolphs social and political thinking to create a new and different intellectual portrait of one of the most important figures in twentieth-century American social history.

This book is printed on acid-free paper.

This book is printed on acid-free paper.