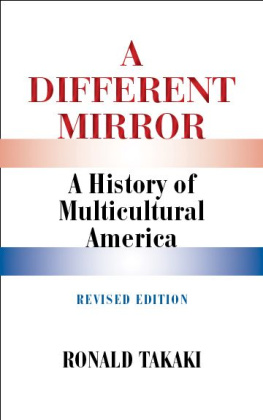

a different mirror

FOR YOUNG PEOPLE

A History of Multicultural America

Ronald Takaki

Adapted by Rebecca Stefoff

Seven Stories Press

New York

2012 by Ronald Takaki

A Triangle Square Books for young readers first edition,

published by Seven Stories Press.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, including mechanical, electronic, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the publisher.

seven stories press

140 Watts Street, New York, NY 10013

www.sevenstories.com

College professors may order examination copies of Seven Stories Press titles for a free six-month trial period. To order, visit www.sevenstories.com/textbook or send a fax on school letterhead to

(212) 226-1411.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Stefoff, Rebecca, 1951

A different mirror for young people : a young peoples history of multicultural America / by Ronald Takaki ; adapted by Rebecca Stefoff.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-1-60980-484-8 (hbk. : alk. paper) -

ISBN 978-1-60980-416-9 (pbk. : alk. paper)

1., Minorities--United States--History--Juvenile literature. 2., United States--Race relations--Juvenile literature. 3., United States--Ethnic relations--Juvenile literature. 4., Cultural pluralism--United States--History--Juvenile literature., I. Takaki, Ronald T., 1939-2009. Different mirror. II. Title.

E184.A1T335 2012

305.800973--dc23

2012017004

Printed in the USA

9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Dedicated to our grandchildren

Nicholas, Alexis, Zo, Cooper, and Mia Takaki;

Rachael and Tanner Aikens

Contents

Introduction

Chapter One

Chapter Two

Chapter Three

Chapter Four

Chapter Five

Chapter Six

Chapter Seven

Chapter Eight

Chapter Nine

Chapter Ten

Chapter Eleven

Chapter Twelve

Chapter Thirteen

Chapter Fourteen

Chapter Fifteen

Chapter Sixteen

Chapter Seventeen

Introduction

My Story, Our Story

I was going to be a surfer , not a scholar.

I was born and grew up in Hawaii, the son of a Japanese immigrant father and a Japanese-American mother who had been born on a sugarcane plantation. We lived in a working-class neighborhood where my playmates were Japanese, Chinese, Portuguese, Korean, and Hawaiian. We did not use the word multicultural, but thats what we were: a community of people from many cultural, national, and racial backgrounds.

My father died when I was five, and my mother remarried a Chinese cook. She had gone to school only through the eighth grade, and my stepfather had very little education, but they were determined to give me a chance to go to college. My passion as a teenager, though, was surfing. My nickname was Ten Toes Takaki, and when I sat on my board and gazed at rainbows over the mountains and the spectacular sunsets over the Pacific, I wanted to be a surfer forever.

Then, during my senior year in high school, a teacher inspired me to think about the problems of the world and of being human and to ask, How do you know what you know? In other words, how do you know if something is true? The same teacher inspired me to attend college outside Hawaii, which is how I found myself at the College of Wooster in Ohio in 1957.

College was a culture shock for me. The student body was not very diverse, and my fellow students asked me, How long have you been in this country? Where did you learn to speak English? To them, I did not look like an American or have an American-sounding name. When I fell in love with one of those students, Carol Rankin, she told me that her parents would never approve of our relationship, because of my race.

Carol was right. Her parents were furious. Still, we decided to do what was right for us. When we got married, her parents reluctantly attended. Four years later, when our first child was born, her parents came to visit us in California. After I said, Let me help you with the luggage, Mr. Rankin, Carols father replied, You can call me Dad. His racist attitudes, it turned out, were not frozen. He had changed.

By that time I was working on my Ph.D. degree in American history. I became a college professor at the University of California in Los Angeles and taught the schools first course in African American history. In 1971, I moved to the University of California at Berkeley to teach in a new Department of Ethnic Studies. In the decades that followed, I developed courses and degree programs in comparative ethnic studies, and I wrote several books about Americas multicultural history. My extended family, too, became a multicultural, mixed-race group that now includes people of Japanese, Vietnamese, English, Chinese, Taiwanese, Jewish, and Mexican heritage.

I have come to see that my story reflects the story of multicultural Americaa story of disappointments and dreams, struggles and triumphs, and identities that are separate but also shared. We must remember the histories of every group, for together they tell the story of a nation peopled by the world. As the time approaches when all Americans will be minorities, we face a challenge: not just to understand the world, but to make it better. A Different Mirror studies the past for the sake of the future.

Chapter One

Why A Different Mirror?

I once flew from San Francisco to Norfolk, Virginia, to give a speech at a teachers conference on multicultural education. In the taxi on the way to the conference, the driver, a white man in his forties, chatted with me about the weather. Then he asked, How long have you been in this country?

The question made me wince, even though I had heard it many times before.

All my life, I said. I was born in the United States.

I was wondering because your English is excellent! he replied. He glanced at me in his rearview mirror. To him, I did not look like an American.

Feeling suddenly awkward, we fell silent. I looked at the Virginia scenery and thought about how our route was taking us through the beginning of multicultural America.

Here, on land taken from the Indians, English colonizers founded the settlement of Jamestown in 1607. After they discovered that great profit could be made by growing tobacco and shipping it to England, they wanted more Indian landand people to work it. In 1619, a year before the English Pilgrims landed at Plymouth Rock in Massachusetts, a Dutch slave ship arrived at Jamestown, bringing the first twenty African laborers to the American colonies. From the beginning, this land was multiracial and multicultural.

But it was not my taxi drivers fault that he did not see me as a fellow citizen. What had he learned about Asian Americans in his school courses on US history? He saw me through a filtera version of American history that I call the Master Narrative.

Challenging the Master Narrative

The Master Narrative says that our country was settled by European immigrants, and that Americans are white. People of other races, people not of European ancestry, have been pushed to the sidelines of the Master Narrative. Sometimes they are ignored completely. Sometimes they are merely treated as the Otherdifferent and inferior. Either way, they are not seen as part of Americas national identity.

The Master Narrative is a powerful story, and a popular one. It is deeply embedded in our culture, in the writings of many scholars, and in the ways people teach and talk about American history. But the Master Narrative is inaccurate. Its definition of who is an American is too narrow.

Next page