Table of Contents

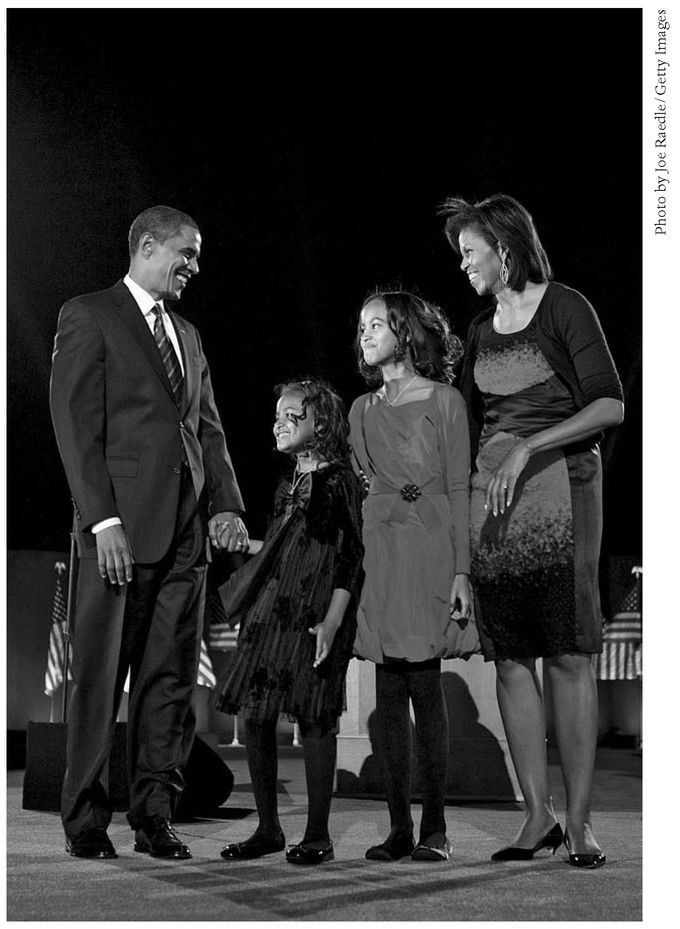

U.S. President-elect Barack Obama stands onstage along with his wife Michelle and daughters Malia (red dress) and Sasha (black dress) in Grant Park on November 4, 2008, in Chicago, Illinois. Obama defeated Senator John McCain by a wide margin in the election to become the first African-American U.S. president-elect.

PROLOGUE

The Age of Obama

Jon Meacham

HE WAS, ONCE, the consummate outsider. The first time Barack Obama saw the White House was a quarter century ago, in 1984, when he was working as a community organizer based at the Harlem campus of the City College of New York. President Reagan was proposing reductions in student aid. The young Obama, just out of Columbia, got together with student leadersmost of them black, Puerto Rican, or of Eastern European descent, almost all of them the first in their families to attend collegeto take petitions protesting the cuts to the New York delegation on Capitol Hill. Afterward, Obama wrote in The Audacity of Hope, the group wandered down Pennsylvania Avenue to the Washington Monument and then to the White House, where they stood outside the gates, looking in.

The glib literary move at this point would be to note how Obama, who will become the forty-fourth president of the United States on Jan. 20, 2009, will now return to that house to undo the work that was unfolding inside all those years agothe work of the Republican Party of Nixon, Reagan and George W. Bush. But the story, like Obama himself, is more complicated than one might think. The Democratic Partys success in 2008 is not a straightforward revenge-of-the-left drama. Many true believers say this is the dawn of a new progressive era, a time of resurgent (and in many ways rethought) liberalism. The highly caffeinated have high hopes. At the same time, many conservativesmost, it seems, with a show on Fox News Channelsee things the same way, and believe an Age of Obama will be a grim hour of redistribution at home and weakness abroad.

But if Obama governs as he ranfrom the centerthen there will be disappointed liberals and conservatives. The left may feel somehow cheated, and the right, eager to launch perpetual assaults on the new administration, could well find Obama as elusive and frustrating as the opposition found Reagan.

Parallels from the past risk seeming irrelevant and antique given the enormity of the historical moment. A nation whose Constitution enshrined slavery has elected an African-American president within living memory of days when blacks were denied fundamental human rightsincluding the right to vote. Hyperbole around elections comes easy and cheap, but this is a momenta yearwhen even superlatives cannot capture the magnitude of the change that the country voted for on November 4, 2008. If there is anyone out there who doubts that America is a place where all things are possible; who still wonders if the dream of our Founders is alive in our time; who still questions the power of our democracy, tonight is your answer, Obama told an adoring yet serious throng in Chicagos Grant Park on the night of his election. He alluded to the historic nature of the victory only indirectly. This election had many firsts and many stories that will be told for generations, he said. He did not need, really, to add anything to that: that he was saying the words was testament enough.

Obama ran, in part, by arguing that his candidacy transcended race. Perhaps it did; many of us believed that his skin color, unusual name and unfamiliar background might well cost him the election. As it turned out, he won decisively, a rare feat for a Democratic presidential nominee. Does this mean that America is now beyond black and white? No, but we are much further ahead than we were a year ago. Obamas victory, no matter what ones politics, is a redemptive moment in the life of a nation for which race has been called, simply and starkly, the American dilemma.

John McCain is a man of honor, a patriot who has lived a life of service and devotion to country. He was, however, on the wrong side of history in 2008. Like Hillary Clinton, also a formidable American and public servant, he had the great personal misfortune to be standing in the path of an unstoppable political force. (One of the riddles of the age will be what might have happened had he survived the South Carolina primary in 2000 and defeated Bush for the Republican nomination eight years ago.) External forces, chiefly the economic collapse in the autumn and President Bushs stubbornly low approval ratings, created an environment that made a GOP victory virtually impossible. With a man of Obamas undeniable political gifts on the other side, the task became actually impossible.

Like Franklin D. Roosevelt in 1932 and Reagan in 1980, the Obama win of 2008 marks a real shift in real time. It is early yet, but it is not difficult to imagine that we will, for years to come, think of American politics in terms of Before Obama and After Obama. Certainly many of his voters already see the world this way. Exit polls suggest that one of every 10 voters was casting a ballot for the first time, and they were overwhelmingly minority or young. Eighteen- to 24-year-olds accounted for roughly the same percentage of the electorate17 percentas they did in 2004, but while the split four years ago was 54-40 percent for John Kerry, it was 68-30 percent for Obama, a net swing of 24 points in Obamas favor, which was by far the biggest shift in any age group.

Their battles are not the battles of their fathers and mothers. Why, Obama once asked someone he identified only as an old Washington hand, did the capital of the first decade of the 21st century feel so much harsher than the postwar era? Its generational, the man replied. Back then, almost everybody with any power in Washington had served in World War II. We mightve fought like cats and dogs on issues. A lot of us came from different backgrounds, different neighborhoods, different political philosophies. But with the war, we all had something in common. That shared experience developed a certain trust and respect. It helped to work through our differences and get things done. That version of the past was heavily edited: Joe McCarthy was a veteran, too.

Still, the point stands. Shared experiences tend to create shared values. Even the epic events of recent yearsSeptember 11, Iraq, the economic crisiscannot begin to give the Obama coalition anything like World War II to smooth the rough edges of partisanship. His voters share convictions, not experiences. Chief among these convictions is a passion for a change from the rule of George W. Bush and an unabashed love for Barack Obama.

In this light, Obama has more in common with Reagan than appearances might suggest. Reagans loyalists believed in his issues, or at least one of his issues, and they believed in him. They were anxious for a change from the incumbent administration at a time of shattered confidence and economic turmoil. The comparison is revealing, for it may foreshadow the nature of the next four or eight years. Like Reagan, Obama is an astute performer, a maker of myths and a teller of stories. Like Reagan, he is popularly seen, by friend and foe alike, as an ideological puristbut has demonstrated a tendency toward the pragmatic. Like Reagan, he is the leader of a core of believers so convinced he is on their side that they are likely to forgive him his compromises.