Copyright 2019 by Evan W. Thomas

All rights reserved.

Published in the United States by Random House, an imprint and division of Penguin Random House LLC, New York.

R ANDOM H OUSE and the H OUSE colophon are registered trademarks of Penguin Random House LLC.

Names: Thomas, Evan, author.

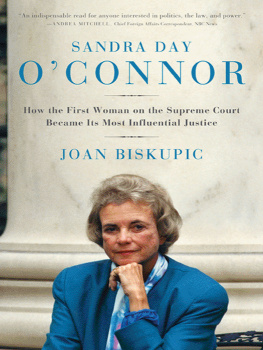

Title: First : Sandra Day OConnor / Evan Thomas.

Description: New York : Random House, 2019. | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2018040502| ISBN 9780399589287 (hardback) | ISBN 9780399589294 (ebook)

Subjects: LCSH: OConnor, Sandra Day, 1930 | Women judgesUnited StatesBiography. | United States. Supreme CourtOfficials and employeesBiography. | BISAC: BIOGRAPHY & AUTOBIOGRAPHY / Women. | LAW / Legal History. | HISTORY / United States / 20th Century.

Classification: LCC KF 8745. O 25 T 46 2019 | DDC 347.73/2634 [B] dc23

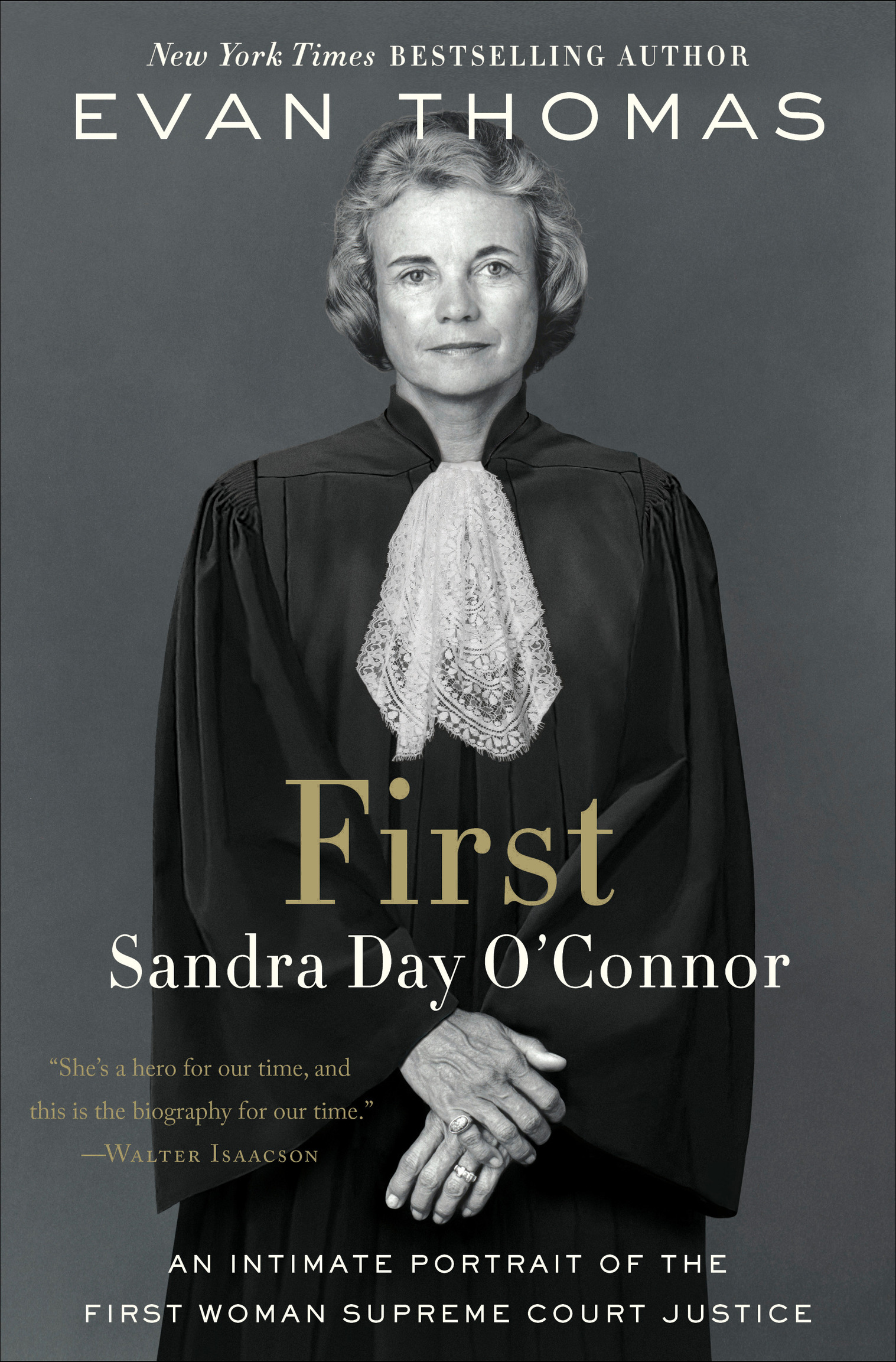

Cover photograph: based on an original photograph by Michael Arthur Worden Evans, 1982, gelatin silver print (National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution/gift of the Portrait Project, Inc.)

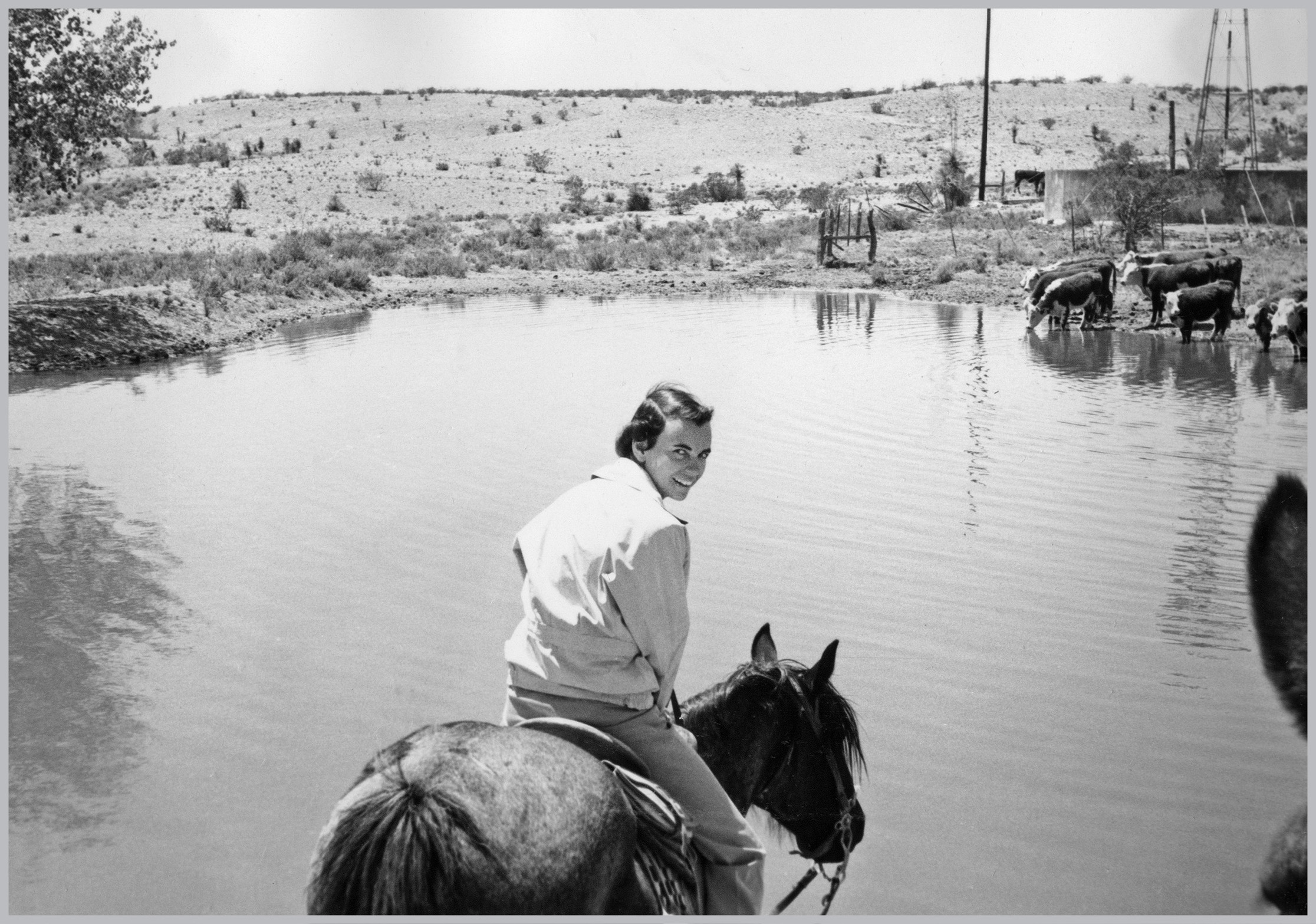

On horseback at the Lazy B. Sandra learned to brand a calf and fire a rifle before she was ten, and to drive a truck as soon as she could see over the dashboard.

In 1981, when Ronald Reagan nominated Sandra Day OConnor to become the first female justice on the Supreme Court, the bulletin led every TV news broadcast and major newspaper in the country and many abroad. The cover of Time magazine read simply JUSTICEAT LAST .

OConnors confirmation hearing that September quickly became a huge media event. There were more requests for press credentials than there had been for the Senate Watergate Committee hearings in 1973. A new media institutioncable TVcarried the hearings live, a first for a judicial nomination. Tens of millions of people saw and heard a composed, radiant, hazel-eyed woman with a broad gap-toothed smile and unusually large hands testify for three days before middle-aged men who seemed not quite sure whether to interrogate her or open the door for her. The vote to confirm her was unanimous.

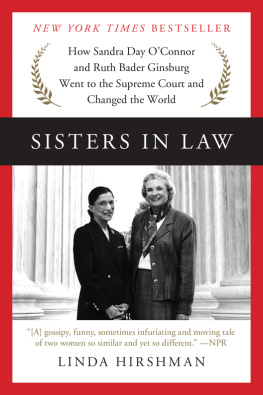

Nearly sixteen years before Madeleine Albright became secretary of state, a dozen years before Ruth Bader Ginsburg joined OConnor on the bench, two years before Sally Ride flew in space, Sandra OConnor entered the proverbial room where it happens. No woman had ever sat in one of the nine chairs at the mahogany table in the oak-paneled conference room where the justices of the United States Supreme Court meet to rule on the law of the land. By the 1980s, women had begun to break through gender barriers in the professions, as well as in the academy and the military, but none had achieved such a position of eminence and public power. The law had been an especially male domain. When she graduated from Stanford Law School in 1952, established law firms were not hiring woman lawyers, even if, like OConnor, they had graduated near the top of their class.

OConnor did not regard herself as a revolutionary. Her success was owed in no small part to her ability to marry ambition to restraint. She was a person for all seasons, said Ronald Reagan when he nominated her for the Court. She saw herself as a bridge between an era where women were protected and submissive toward an era of true equality between the sexes. At the same time, she saw that women might have to work twice as hard to get ahead; that men might be threatened or at the very least unsure about the new order; and that there was no use fretting about it. She understood that she was being closely watched. Its good to be first, she liked to say to her law clerks. But you dont want to be the last.

I N HER CHAMBERS at the Supreme Court that autumn of 1981, the mail poured in by the truckloadtens of thousands of letters, many supportive, some not. A few were from angry men who sent naked pictures of themselves. OConnor was taken aback by this ugly, primitive protest against the presence of a woman on the Court, but she had learned how to shrug off insults, snubs, and innuendo and focus on the job at hand.

At the traditional opening of the Court term, on the first Monday in October, OConnor took her place at the end of the long mahogany bench above where the lawyers would argue. As the first case was presented, the other justices immediately began firing questions at the lawyer standing at the lectern ten feet away. For thirty minutes, as the legal arguments and questions flew back and forth in a complex case involving oil leasing, she remained silent. Shall I ask my first question? OConnor wondered. I know the press is waitingAll are poised to hear me, she wrote later that day, re-creating the scene in her journal. From her seat on the high bench, she began to ask a question, but almost immediately the lawyer talked over her. He is loud and harsh, OConnor wrote, and says he wants to finish what he is saying. I feel put down.

She would not feel that way for long. She was, in a word, tough. She could be emotional; she laughed easily and was not ashamed to cry in private, though never over embarrassment or small slights. But she refused to brood and instead forged ahead. She knew she was smarter than most (sometimes all) of the men she worked with, but she never felt the need to show it.

The Court is large, solemn. I get lost at first, she wrote in her journal on September 28, 1981. It is hard to get used to the title of Justice. A few of the other justices seemed genuinely glad to have me there, she wrote. Others seemed guarded, not only around her but even around each other. At the regularly scheduled lunch in the justices formal dining room that week, only four of her colleaguesChief Justice Burger and Justices Stevens, Brennan, and Blackmunshowed up. The room is cold, OConnor wrote.

OConnor soon set about warming it up. The justices, she was surprised to discover, rarely spoke to one another; they preferred to communicate by memo. So she made it her custom to cajole her brethren into attending the weekly lunches, sometimes just sitting in their offices until they agreed to come along. She had long appreciated the simple truth that if people get to know each other in a relaxed setting, they are more likely to find common ground. As the first female majority leader of a state senate, in Arizona during the early 1970s, she had from time to time gathered her colleagues from both political parties around her swimming pool and plied them with Mexican food (and beer, plenty of beer, she recalled). She needed to know them and how they thought. She needed them to vote for her bills.