To the memory of my father

Joseph Shlaim,

19001971

CONTENTS

I T IS A PLEASURE to introduce the second edition of The Iron Wall: Israel and the Arab World to the reader. This book first appeared in 2000; it was issued in paperback a year later and has proved a surprising publishing success for an obscure academic. As well as many printings of its editions in the United States (Norton) and United Kingdom (Allen Lane/Penguin), the book has been translated into Arabic, Hebrew, French, Italian, Spanish, Portuguese, and Japanese, and German and Turkish editions are in the pipeline. The unexpectedly wide readership that the book has enjoyed, and the positive reviews it received on both sides of the Atlantic, have encouraged me to undertake the work for a second edition.

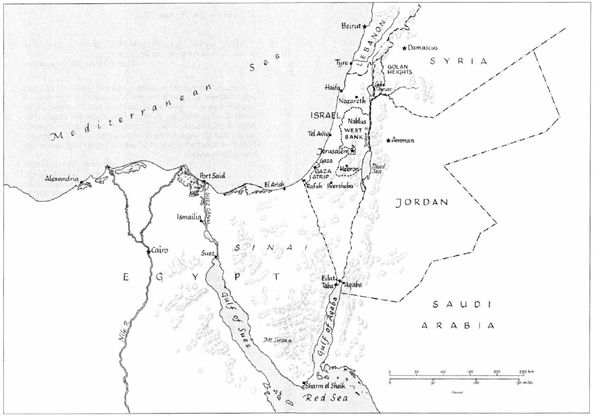

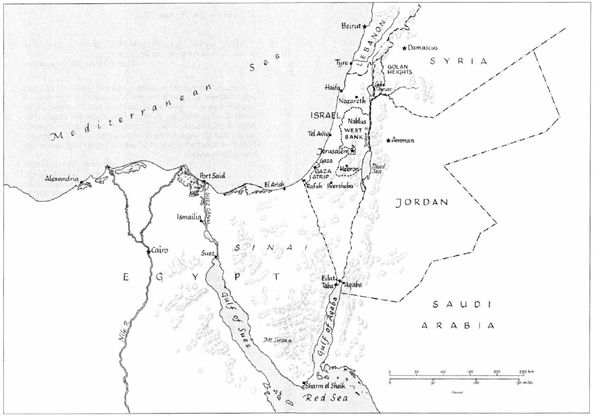

The first edition of The Iron Wall was a detailed study of Israels policy toward its Arab neighbors in the first fifty years of statehood, from 1948 to 1998. For this second edition, I have made only minor corrections and revisions in the original text. This book substantially expands and updates the original text to take the story from 1998 to January 2006, when Prime Minister Ariel Sharon fell into a coma and was succeeded by Ehud Olmert. It includes an additional section in on Binyamin Netanyahu, taking the story from 1998 to the end of his first term in office in 1999; two new chapters on Ehud Barak, 19992001; and two new chapters on Ariel Sharon, covering the period 200106. I have also added an epilogue and two maps, and have updated the chronology and the bibliography.

Although I am a scholar by profession and, as such, committed to high standards of objectivity, I cannot claim to write about the Arab-Israeli conflict with clinical detachment. The reason for this is that I have been involved in this conflict in one way or another all my life. A word about my own background might therefore be in order. I was born in Baghdad to an Iraqi-Jewish family in 1945. In 1950, following the first Arab-Israeli war, we were part of a major exodus of Jews from Iraq to Israel. We were not refugees, we were not mistreated, and we were certainly not pushed out, but in a real sense we were victims of the Arab-Israeli conflict. My family had probably lived in Iraq since the Babylonian exile two and a half millennia ago. We were Arab Jews, we spoke Arabic at home, and we had always lived in harmony with our Muslim neighbors. My parents had little knowledge of and no sympathy for the Zionist cause. As a result of circumstances completely beyond their control, we were suddenly uprooted and transplanted to the newborn state of Israel. My father never recovered from the ordeal of exile from his native land. In Iraq he was a wealthy merchant with a high social status; in Israel he was a broken man. He used to say with a deep sigh, The Jews prayed for a state of their own for two thousand years, and they prayed in vain; did it have to happen in my lifetime?! This book is dedicated to his memory.

I grew up in Israel and I did national service in the Israel Defense Force in the mid-1960s, but I received all my university education in Britain, first in history at Cambridge and then in international relations at the London School of Economics. For the last forty-four years I have been a university teacher in Britain, first at Reading and then at Oxford. At Oxford I was a professor of international relations, a fellow of St. Antonys College, and a member of its Middle East Centre from 1987 until my retirement in 2011.

At the beginning of my academic career I made a conscious decision to steer clear of the Arab-Israeli conflict; it was too near the bone. My two main research interests, and my early publications, were political integration in Western Europe and the Cold War. The Ph.D. thesis that became my first book was on the United States and the Berlin blockade of 194849, a study in crisis decision making. Gradually, however, my interests shifted to the Middle East. To begin with, I had fairly conventional views about the justice of Israels cause and about the origins and causes of the Arab-Israeli conflict. Broadly speaking, I accepted the traditional Zionist version of events that I had been taught at school. As a result of research and observation of Israels actual conduct, however, I slowly began to develop a more critical perspective. I still accept the legitimacy of the State of Israel within the pre-1967 borders. What I reject, and reject totally and uncompromisingly, is the Zionist colonial project beyond the 1967 borders. It was particularly distressing to see the IDF, which in my day was true to its name and in which I served loyally and proudly, transformed into the police force of a brutal colonial power.

Zionist and pro-Zionist historians have tended to portray Israel as a peace-loving nation that goes to war only when there is no other choice. According to this school of thought, the fundamental cause of the Arab-Israeli conflict since 1948 has been Arab rejection of Israels legitimacy and Arab diplomatic intransigence. In the late 1980s, however, this standard Zionist version of the conflict began to be subjected to critical scrutiny by a group of new or revisionist Israeli historians. The term new historiography was coined by Benny Morris in an article that first appeared in 1988 in Tikkun , the liberal American-Jewish magazine, and was later reprinted in various places. The title of the article was The New Historiography: Israel and Its Past. The adjective new was perhaps too dramatic and more than a shade self-congratulatory. It was also misleading in that it implied the development of a new methodology in the study of history. In fact the new historians used a conventional historical method; it was the material they found in archives and reported in their books and articles that was new, or at least partly new. New history was not a methodological innovation but proper historyhistory based on archival research, primary sources, and official documents. But the term new history gained general currency in the debate about Israels past, and I, too, took to using it in the absence of a better alternative.

The main factor that helps to account for the emergence of the new history was the release of the official documents by the government of Israel under the thirty-year rule. This rule governs the review and declassification of official documents. Israel copied this rule from Britain and applies it in a commendably liberal fashion. I already observed in the preface to the first edition that it is very much to Israels credit that it allows access to its internal records and thereby makes possible critical scholarship about its foreign policy. Access to the official records makes it possible to write with some confidence, or at least with the support of some hard evidence, about the perceptions, the thinking, the intentions, the aims, the strategy, and the tactics of Israels foreign policy makers. Another factor was the change in the climate of opinion in Israel in the aftermath of the Lebanon War of 1982. For many Israelis, especially liberal-minded ones, the Likuds ill-conceived and ill-fated invasion of Lebanon in 1982 marked a watershed. Until then, Zionist leaders had been careful to cultivate the image of peace lovers who would stand up and fight only when war was forced upon them. Until then, the notion of ein breira , of no alternative, was central to the explanation of why Israel went to war and a means of legitimizing its involvement in wars. But while the fierce debate between supporters and opponents of the Lebanon War was still raging, Prime Minister Menachem Begin gave a lecture at the National Defense College on wars of choice and wars of no choice. He argued that the Lebanon War, like the Sinai War of 1956 and the June 1967 War, was a war of choice designed to achieve political objectives. With this admission, unprecedented in the history of the Zionist movement, the national consensus around the notion of ein breira began to crumble, creating political space for a critical reexamination of the countrys earlier history.

Next page