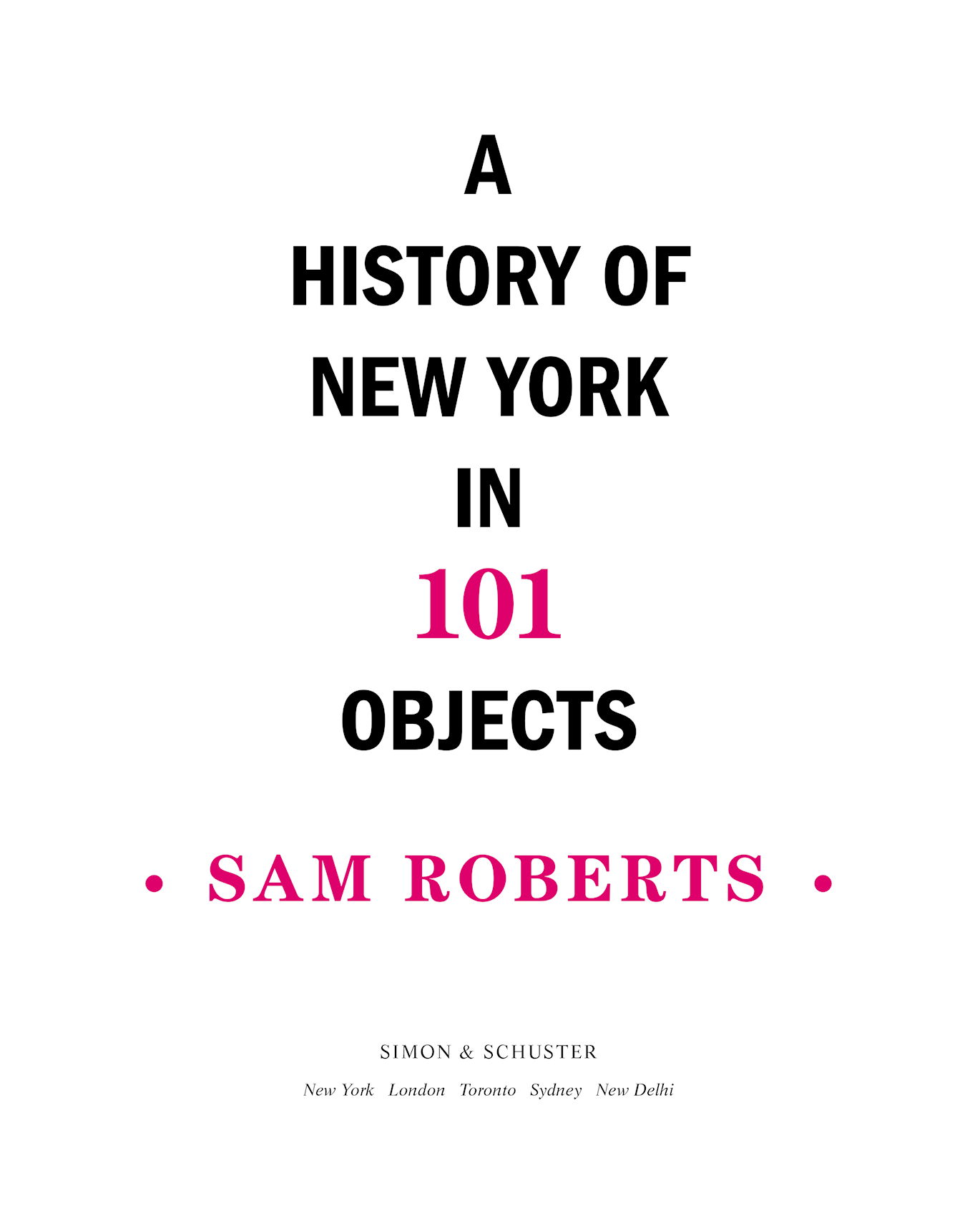

Simon & Schuster

1230 Avenue of the Americas

New York, NY 10020

www.simonandschuster.com .

Copyright 2014 by Sam Roberts

All rights reserved, including the right to reproduce this book or portions thereof in any form whatsoever. For information address Simon & Schuster Subsidiary Rights Department, 1230 Avenue of the Americas, New York, NY 10020.

First Simon & Schuster hardcover edition September 2014

SIMON & SCHUSTER and colophon are registered trademarks of Simon & Schuster, Inc.

For information about special discounts for bulk purchases, please contact Simon & Schuster Special Sales at 1-866-506-1949 or business@simonandschuster.com .

The Simon & Schuster Speakers Bureau can bring authors to your live event. For more information or to book an event contact the Simon & Schuster Speakers Bureau at 1-866-248-3049 or visit our website at www.simonspeakers.com .

Interior design by Joy OMeara

Jacket design by Marlyn Dantes

Jacket photographs ( top to bottom ): arrowhead American Museum of Natural History; statue Niko Koppel; World Trade Center dust New-York Historical Society; keg from Erie Canal New-York Historical Society; badge Tony Cenicola/Redux Pictures; Phantom of the Opera mask Tony Cenicola/Redux Pictures; yellow cab Image Source/Corbis; bagel Lisa Larson-Walker; coffee cup Tony Cenicola/Redux Pictures

Library of Congress Control Number: 2013050297

ISBN 978-1-4767-2877-3

ISBN 978-1-4767-2880-3 (ebook)

I.G.Y. (What a Beautiful World). Words and music by Donald Fagen. Copyright 1982 Freejunket Music (ASCAP). All rights reserved. Used by permission.

This Land Is Your Land. Words and music by Woody Guthrie. WGP & TRO- Copyright 1956 (Renewed) 1958 (Renewed) 1970 (Renewed) 1972 (Renewed) Woody Guthrie Publications, Inc. & Ludlow Music, Inc., New York, NY. Administered by Ludlow Music, Inc. Used by Permission.

To Dylan and Isabella

It is only in the world of objects that we have time and space and selves.

T. S. Eliot

Introduction

A teddy bear or other childhood totem. That game-winning high school football. A Beatles concert ticket stub from Shea Stadium. The fraternity pin from you-know-who. A grandchilds first tooth. Your retirement watch from work.

Imagine having to choose just one object that defined your life.

Which one would it be?

Searching for paradigmatic but quirky artifacts that define the past is an irresistible parlor game. A few years ago, the British Museum and BBC Radio compiled A History of the World in 100 Objects. When I played a local version for The New York Times, though, their 100-object cap proved too confining. Call it a conceit, but doing justice to the history of a city this big took 101.

The criteria for this kaleidoscopic History of New York in 101 Objects were not arbitrary. My choicesfrom an artichoke to an elevator safety brake, a public high school yearbook to a cheap handgun, a skeletal model of King Kong sans rabbit fur to a mechanical cotton pickerwere highly subjective. The objects themselves had to have played some transformative role in New York Citys history or they had to be emblematic of some historic transformation. They also had to be enduring, which meant they could not be disproportionately tailored to recent memory or contemporary nostalgia. Fifty, or even twenty-five years from now, would they seem as vital or archetypal as they do right now? The closer you get to the now, the more objects you can think of, but their longevity is harder to get a sense of, Dr. Jeremy D. Hill, the British Museums research manager, told me. When the British public was asked to nominate objects for our list, the vast majority were only one generation old. But in two hundred years time, how many of these would you choose to be talking about?

That meant leaving out lots of twenty-first-century objectsfrom Volume I, at least.

The British Museum and other institutions that have compiled similar lists generally limited themselves to items in their own collection. We imposed no such boundariesonly that an object could not be a human being, alive or dead (Mayor Ed Koch, who died in 2013, got the most nominations from Times readers). Nor too much bigger than a breadbox (which ruled out Central Park, the Empire State Building, the Statue of Liberty, the Parachute Jump, Washington Square Arch, the Staten Island Ferry, and the Unisphere, among many others). The object had to have existed someplace and at some time and still survive in some form (only one in our list could not be found). Our objects could come from any place, but they had to illuminate great New York movements or great moments, personify individuals who played an outsize role in the citys development, or typify epochal transmutations in its ongoing metamorphosis.

With those goals in mind, the 101 objects in this book were winnowed from hundreds of possibilities.

People and events shape history, but do inanimate doodads? Recently, in writing a book about Grand Central Terminal, I learned that even a single building could be transformational. Grand Central epitomized a convulsion in civil rights, communication, landmarks preservation, and urban planningthe terminal shifted Manhattans cultural center of gravity to its very doorstep. By weaving its way into the fabric of American culture, this majestic beaux arts monument to civic and corporate pride embodied the soul of the city and a locus of new beginnings.

Still, a building is one thingeven one located in Skyscraper National Park, as Kurt Vonnegut called Manhattan. Can a single object affect, much less make, history? Of course. Where would we be without the wheel, much less a crucifix or a credit card (Brooklyn is the Borough of Churches, and the first bank charge card was invented there in 1946). You can find the entire cosmos lurking in its least remarkable objects, Wisawa Szymborska, the Polish poet, wrote. This book is a biography of material thingsthings, some remarkable, some mundane, that eloquently objectify and illuminate history through their own unique prism. They may be inanimate, but they have taken on lives of their own.

These 101 begin before history, hundreds of millions of years ago, when geology created the physical contours that made New York a natural harbor and downtown and midtown an unshakable foundation for manmade objects, ranging from the metallic spires of soaring skyscrapers to doughy bagels dense enough to be doorstops. The bedrock amphibolite, Fordham gneiss, and Manhattan schist forged by volcanic upheavals weathered millennia. But as Neil MacGregor, the director of the British Museum, observed, A history through objects can never itself be fully balanced because it depends entirely on what happens to survive.

While the earliest objects are in short supply, I try to trace the First Peoples in what became New York, displaced by the early Dutch settlers, whose pragmatic tolerance for diversity distinguished the colony from English, French, and Spanish settlements (but did not rule out kidnapping and enslaving Africans). A century of British rule climaxed in seven years of largely forgotten but miserable occupation by enemy troops during the American Revolution and then a fateful, cunning political calculation to shift the new nations capital to a swamp in the South.

The nineteenth century witnessed gargantuan growth, fueled largely by European immigration and industrialization, which elevated New York into the nations manufacturing and maritime capital (and shaped its ambivalence about the Civil War) and, by the beginning of the next century, into its gilded cultural capital, too. In the twentieth, New York also became the capital of the world. As the new millennium neared, the city struggled on the brink of bankruptcy and chaos, but it survived a baptism by fire to begin the twenty-first century stronger and more vibrant than ever.