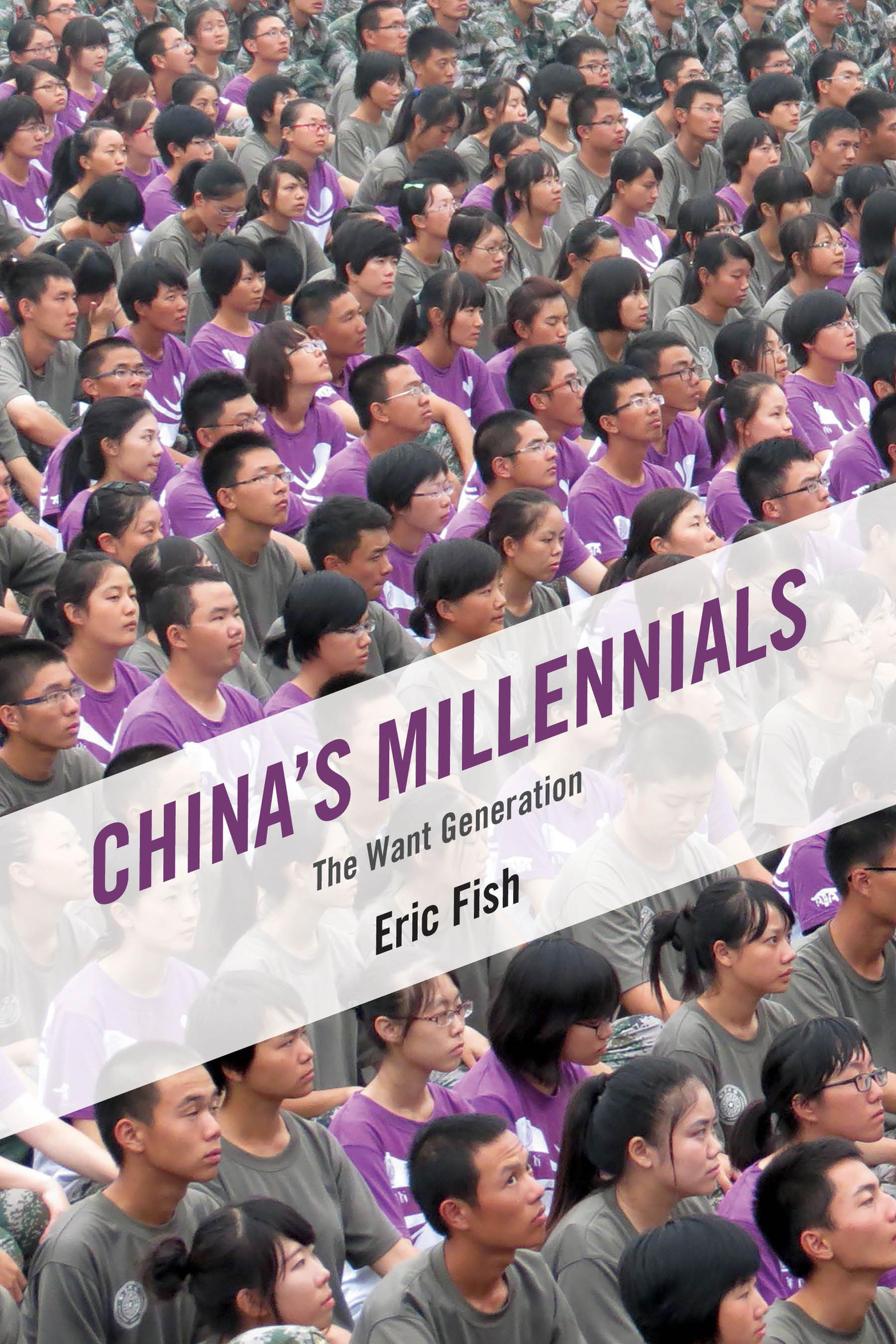

Chinas Millennials

The Want Generation

Eric Fish

ROWMAN & LITTLEFIELD

Lanham Boulder New York London

Published by Rowman & Littlefield

A wholly owned subsidiary of

The Rowman & Littlefield Publishing Group, Inc.

4501 Forbes Boulevard, Suite 200, Lanham, Maryland 20706

www.rowman.com

Unit A, Whitacre Mews, 26-34 Stannary Street, London SE11 4AB,

United Kingdom

Copyright 2015 by Rowman & Littlefield

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, including information storage and retrieval systems, without written permission from the publisher, except by a reviewer who may quote passages in a review.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Information Available

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Fish, Eric, 1985

Chinas millennials : the want generation / Eric Fish.

pages cm

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-1-4422-4883-0 (cloth : alk. paper) ISBN 978-1-4422-4884-7 (electronic) 1. Generation YChina. 2. Youth in developmentChina. I. Title.

HQ799.C5F57 2015

305.20951dc23

2015000751

TM The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information Sciences Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992.

TM The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information Sciences Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992.

Printed in the United States of America

Preface

On June 4, 2014, along Beijings Changan Boulevard, there was little sign that a massacre had unfolded exactly twenty-five years earlier. Shoppers toted bags from a nearby mall. Elderly women shuffled by on their morning walks. Suited businessmen filed toward their offices. All that distinguished the day from any other were the watchful public security officials stationed every few hundred feet.

At Tiananmen Square, where the protests that had prompted the massacre occurred, it was the same story. The only commemorations were those of tourists marking their trip to the capital with pictures in front of the famous Mao Zedong portrait. Those few trying to remember the events of 1989 mostly found themselves intercepted by police before they could even make it to the square. If anyone tried to post something online, it was scrubbed by censors within minutes. Thus, most of the remembering was left to foreign media.

Among the hundreds of reports in the run-up to the anniversary, many sought to compare those youth who had demonstrated in 1989 to those born after the events. In nearly all cases, the comparison reflected rather poorly on the latter. Some illustrated a state-induced amnesia that had taken hold. One reporter showed the iconic photo of Tank Man, the unidentified protestor who blocked a column of tanks the day after the massacre, to a hundred college students in Beijingto which all but fifteen pleaded ignorance.

While accounts like these were undoubtedly true, there were facets to the story not quite captured, and it reminded me why I had first wanted to write this book. Shortly after the June 4 anniversary, I told a Chinese friend in Beijing that I was writing about youth in modern China. Be sure to say that we post-90s people (jiulinghou) arent just idiots, he suggested. Foreigners always think were brainwashed.

But foreigners were not the only ones selling them short. Young Chinese I was speaking to, like many youth around the world, also seemed to feel older generations at home were pigeonholing them into unflattering stereotypes. When I said I was writing about typical young people like them, they became anxious to air their grievances and struggles, as well as to defend themselves against those who would look down upon them. You should write about the fuerdai, said another Chinese friend, referring to spoiled children of the wealthy. And how losers like me cant get a job, he added with a chuckle.

I came to China in 2007 to teach at a university. Age twenty-two at the time, I was assigned to work with students just a few years younger than myself. We were all millennialsloosely defined as the generation born in the 1980s and 1990s (for the purposes of this book, we will say 1984 to 1996).

I quickly discovered many threads that united the Chinese youth whom I was meeting and my American peers back home. Psychologist Jean Twenge called us Generation Me in her 2006 book of the same name. Through extensive surveying, she concluded that American millennials tend to be tolerant, confident, open-minded, and ambitious, but also cynical, depressed, lonely, and anxious. She drew her book title from the strong sense of entitlement and narcissism that she identified among this cohort relative to earlier generations.

Chinas millennials get the same labels, often with survey data to back them up. Like their counterparts in America and around the world, they were raised in relative comfort compared to earlier generations, leading to somewhat lofty expectations. Thanks to the one-child policy, instituted in 1979 as a way to rein in the enormous population, Chinas generation of little emperor only children have a reputation for being especially spoiled. But like their international counterparts, they are also growing into the economic and social uncertainty of a postrecession world and struggling to stay on the better end of a yawning wealth gap, arousing great anxiety about the future.

However, the Sino-American similarities start to diverge once politics is factored in. American millennials came of age as their country was triumphing in the Cold War. As the Berlin Wall fell in 1989 and the Soviet Union crumbled two years later, these youth were brought up confident as ever that their political system represented the so-called End of History. Chinas millennials, however, were born amid the 1989 crackdown at Tiananmen Squareone of the most transformative events in recent Chinese history. The seven weeks of protests that year and the bloody suppression that ended them were tantamount to a reset button for Chinas Communist Party (the CCP) and Chinese society as a whole. Amid an ideological vacuum that had helped prompt the protests, insecure leaders had to reinvent their country and justification for ruling over it. So over the following two decades, everything changedsometimes for the better, sometimes notand a generation gap between the Tiananmen and post-Tiananmen youth seemed to emerge, again with both positive and negative implications. The economy boomed for Chinas millennials, but the bigger political questions that their parents had raised at Tiananmen were put on the shelf.

During my three years as a teacher in Nanjing, I indeed saw depressing signals of political apathy and submissiveness. Jiang Fangzhou, a Chinese writer born in 1989, recognized this prevailing attitude as an active effort to maintain the status quo, saying that young Chinese today dare not stray from the orthodoxy for even one millimeter when they are still 10 meters away from crossing the line.

Chinese youth since the uprising of 1989 have largely been kept happy by the Community Partys emphasis on opening up economic opportunities, but many signs point to a growing dissatisfaction with purely material goals and to an increasing likelihood that young Chinese will again become a vocal force for change.

After teaching, I went on to study journalism at Tsinghua University in Beijing, and later worked at a Chinese investigative newspaper with young native reporters. During my reporting at

Next page

TM The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information Sciences Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992.

TM The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information Sciences Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992.