FEAR ITSELF

The New Deal

AND THE

Origins of Our Time

IRA KATZNELSON

For Deborah, and her

ever-expanding bounty

I live in an age of fear.

E. B. White, letter to the

New York Herald Tribune,

November 29, 1947

CONTENTS

L ESS THAN A YEAR after Franklin Roosevelt assumed the presidency, Charles Beard, the nations leading historian, reported how, with astounding profusion, the presses are pouring out books, pamphlets, and articles on the New Deal. Indeed, we possess hundreds of thematic histories, countless studies of public affairs, and abundant biographies of key persons during this time of great historical density. Scholars and journalists have exhaustively analyzed the epochs increasingly powerful bureaucracy, the Supreme Court as it evolved, the thicket of policies concerning economic regulation and social welfare, and the countrys growing military capacity and global leadership. Their resonant pages emphasize the character, the actions, and prose of its two presidentsone mesmerizing, larger than life, the other plain but not simple. They are crowded with other grand characters we have come to know well, including the grandiloquent union leader, John L. Lewis; the lanky congressman and senator from Texas, Lyndon Baines Johnson; the erudite African-American scholar and activist, W. E. B. Du Bois; and a colorful parade of spies and spy catchers, radio preachers and generals, atomic scientists and war-crimes lawyers.

With the protean twenty-year epoch of Democratic Party rule long understood as a watershed... that separates politics past from politics present and future, why present another portrait of the New Deal? Is there anything new to be said about this defining timelike the Revolution and the establishment of the new nationthat set... the terms of American politics and government for generations to come?

I.

D RAWN TO the mystery and beauty of Venice, Henry James set numerous sketches, stories, and novels in that city, where the mere use of ones eyes... is happiness enough.

James defended his depiction. It is not forbidden... to speak of familiar things or present a fillip to... memory when a writer is himself in love with his theme. One reason for writing is just such veneration. The New Dealthe designation I use for the full period of Democratic Party rule that begins with FDRs election in 1932 and closes with Dwight Eisenhowers two decades laterreconsidered and rebuilt the countrys long-established political order. In so doing, it engaged in a contest with the dictatorships, of both the Right and the Left, about the validity of liberal democracy. Bleak uncertainty marked most of these years. By successfully defining and securing liberal democracy, the New Deal offers the past centurys most striking example of how a democracy grappled with fear-generating crises.

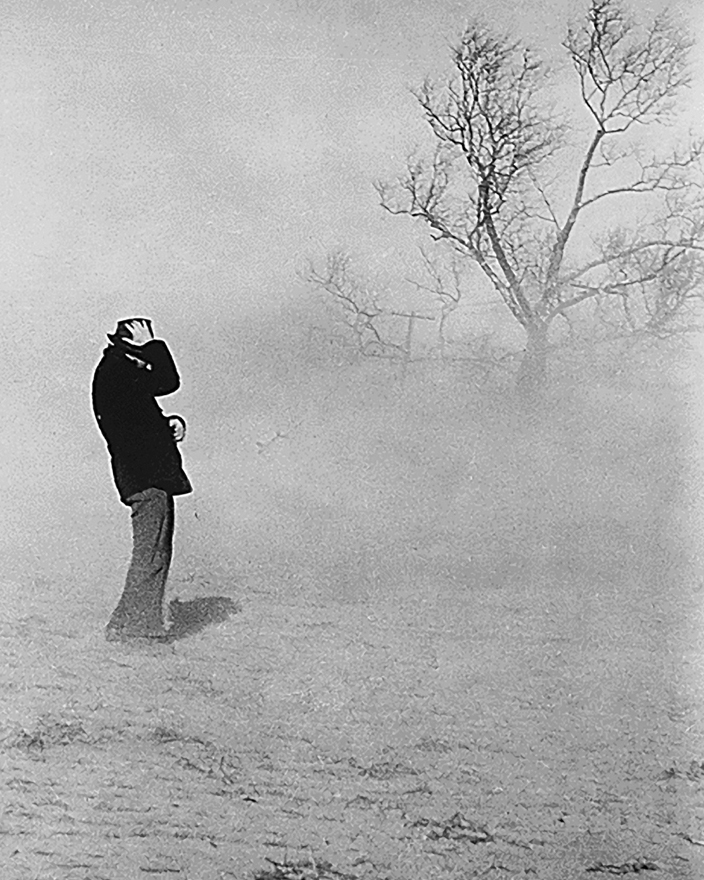

A gloom of incomparable force was setting in when the New Deal began. In July 1932, Benito Mussolini celebrated, if prematurely, how the liberal state is destined to perish. Reporting how worn out constitutional democracies had been deserted by the peoples who feel [it will] lead the world to ruin, he boasted, in prose ghostwritten by the philosopher Giovanni Gentile, that all the political experiments of our day are antiliberal. The New Deals rearrangement of values and institutions, and its support for the Western liberal political tradition, answered this challenge. Its battles were fought on many fronts, from the effort to revive capitalism to the struggle to incorporate the working class and contain the dangerous features of a mass society. Its international objectives were no less weighty, from the mission to defeat Nazi Germany, Fascist Italy, and militarist Japan to the desire to keep Soviet Communism in check, while maintaining internal solidarity and security in the process. These achievements are especially impressive when one realizes that they had to be accomplished virtually all at once, like a galloping Thoroughbred carrying not one rider but four.

From the early days of the New Deal, the democratic world watched with great curiosity. Many were convinced that there was a nearly perfect coincidence between the particular causes of the United States and the universal causes of humanity.

This trust was not misplaced. The New Deal ultimately proved Mussolini wrong. The Gods of liberalism did not die. The dictatorships vortex of violence and brutality was not only met but also trumped by a model of constitutionalism and law. Of the New Deals many achievements, none was more important than the demonstration that liberal democracy, a political system with a legislature at its heart, could govern effectively in the face of great danger.

These achievements were widely recognized, almost immediately so. The editors of The New Republic reviewed the New Deals panoply of policies in May 1940. They persuasively judged the first two Roosevelt administrations to have done far more for the general welfare of the country and its citizens than any administration in the previous history of the nation.

By transcending the limits of traditional liberalism, conservatism, and orthodox socialism to take effective decisions on democracys behalf, the New Deal designed a template of options and possibilities with wide appeal beyond the United States. Marked by the brilliant invocation of democratic resources against the perils of depression and war, that effectively responded to the eras naysayers, who claimed that liberal democracies were too pusillanimous to challenge the treacherous dictatorships, too effete to mobilize their citizens, and too enthralled with free markets to manage a modern economy successfully.

The New Deals sustained defense of liberal democracy surely deserves at least as much admiration as Henry James expressed for golden Venice. Yet with so many facts familiar, archives exhausted, and competing interpretations long established, high regard cannot justify this book, certainly not a book of this length. The question lingers. Why paint, yet again, the most painted political landscape of twentieth-century America?

II.

A WISE COMMENTATOR once wrote of King Lear that the sheer greatness of this work grossly magnifies its defects... that stand between certain scenes and their possible perfection. Esteem for the New Deal paradoxically should draw attention to its most profound imperfections; it should motivate efforts to discern the causes of its defects. Seeking to understand not only the New Deals manifest successes but also its ironies and limitations, I explore the complicated and sometimes unprincipled relationships between democracy and dictatorship, and between democracy and racism. Eschewing the traditional division separating foreign from domestic affairs, the book examines the fringes of liberal civilization and the ways in which illiberal political orders, both within and outside the United States, influenced key New Deal decisions.