For Oscar and Carla

CONTENTS

List of Illustrations

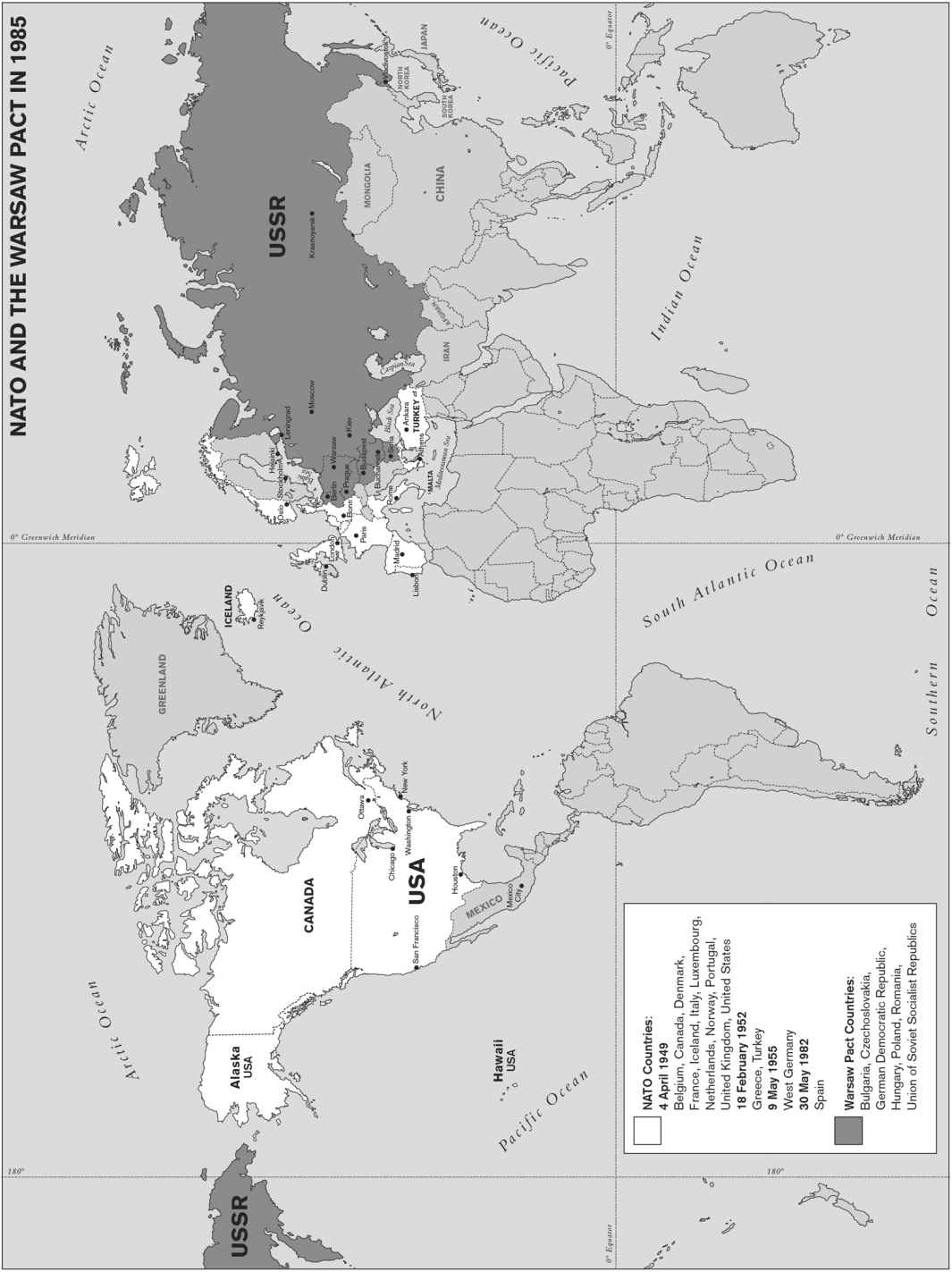

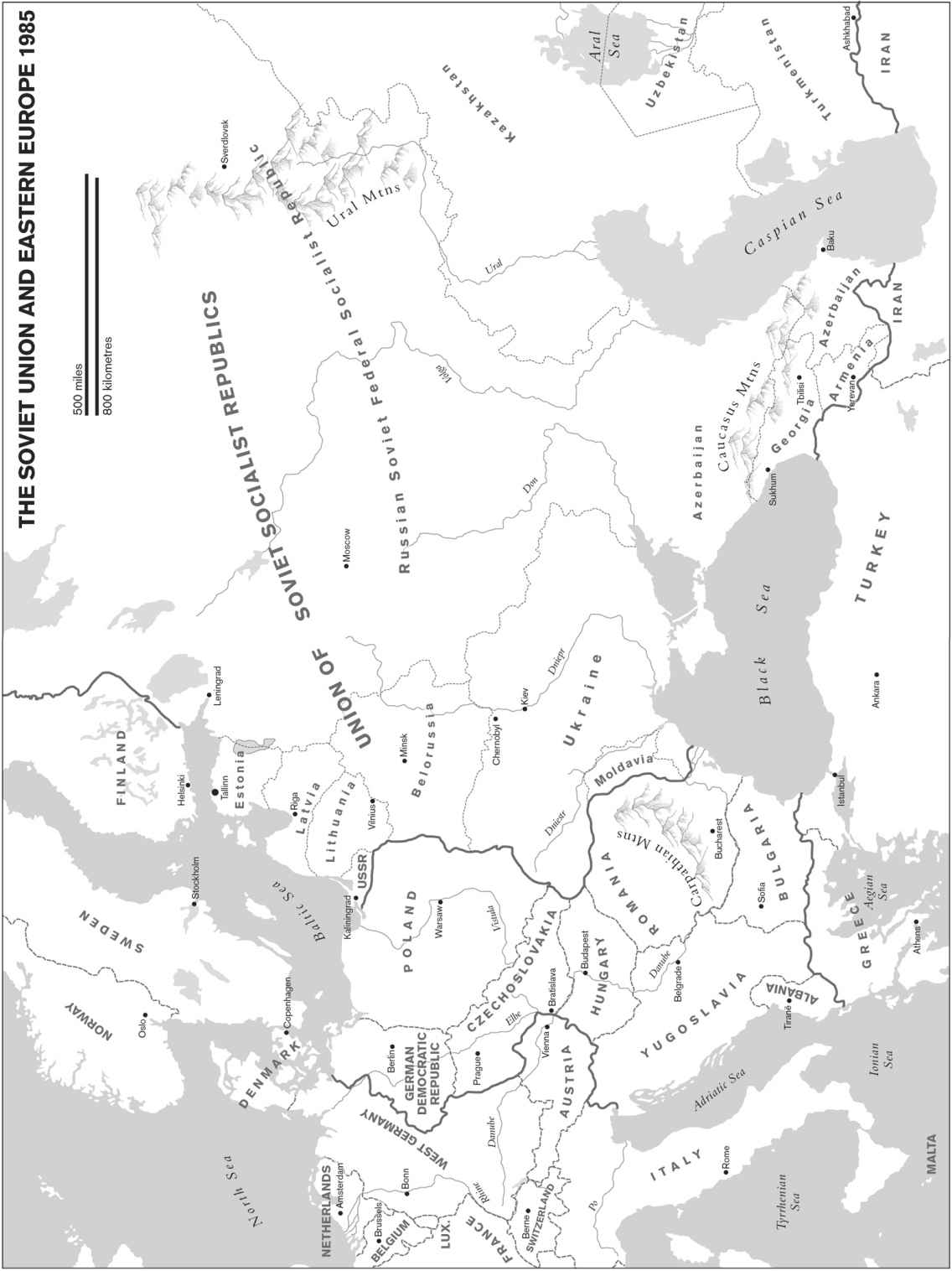

Maps

Preface

The end of the Cold War can now be explored in countless American personal papers, printed collections and online sources. Many are just beginning to be investigated. Soviet material from the Russian vaults is also plentiful even though a lot of it is accessible only in foreign libraries. Diaries and transcripts of meetings and conversations sharpen our picture of a momentous period in world politics. It has become possible, for instance, to trace exactly how Ronald Reagans 1987 Berlin Wall speech underwent its successive revisions or how Soviet leaders amended their words before finalizing the Party Central Committee minutes. The records have to be handled with some caution, not least because politicians filtered what they allowed to be recorded. But it is better to have more archives than fewer. The insights they afford are the foundation stone for this book.

For the Soviet side, Party Politburo minutes are found in the working notes filed by the General Department of the Secretariat. Many of these notes are conserved at the Hoover Institution in its RGASPI Fond 89 and in the papers of Dmitri Volkogonov, who made copies from the Presidential Archive in the early 1990s. Furthermore, several of Gorbachvs associates Anatoli Chernyaev, Georgi Shakhnazarov and Vadim Medvedev ignored the ban on keeping a record of what they witnessed. Their work has appeared in printed form, and in Chernyaevs case I have consulted his papers in the Russian Library at St Antonys College, Oxford. Also of importance is Stanford Universitys collection of the Party Central Committee minutes, which include successive drafts of the proceedings and even speeches that were prepared but not delivered.

The Hoover Institutions collections on leading Soviet figures are among the most informative for the last years of the Cold War. Three are truly outstanding. Foreign Affairs Minister Eduard Shevardnadze asked his aide Teimuraz Stepanov-Mamaladze to take regular notes on his meetings and conversations. The result is an incomparable record of deliberations and decisions in Soviet foreign policy; it is a pleasure to bring them to attention for the first time. Vitali Kataev of the Party Secretariats Defence Department assiduously documented the discussions inside the Soviet leadership on arms reduction. This material is unusually helpful in elucidating the links between the politicians and the military-industrial complex. Anatoli Adamishin, who headed the First European Department in the Foreign Affairs Ministry before his appointment as Deputy Foreign Affairs Minister, kept a diary through the 1980s and beyond. His observations offer an enthralling and largely unexamined source on the USSRs internal politics and international relations.

For the American side, I have consulted the holdings at the Ronald Reagan Presidential Library at Simi Valley, California. The Hoover Institution Archive also contains rich material from the Committee on the Present Danger and from the personal papers of CIA Director William J. Casey and National Security Adviser Richard V. Allen. Crucial for this account are the copious notes taken by Charles Hill during his work with Secretary of State George Shultz: I am grateful to them for allowing me to quote from this exceptional source. In addition, I found much in the National Security Archive at George Washington University, both on site and electronically. I also used the collections at the George H. W. Bush Presidential Library as well as online publications available via Freedom of Information Act requests. David Holloway at Stanford kindly shared his copies of CIA papers. Molly Worthen of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill did the same with some pages from Charles Hills work diary; and I am indebted to Sir Rodric Braithwaite, UK Ambassador to the USSR and the Russian Federation in 19881991, for providing his diary of that period, and to Sir Roderic Lyne, who also served in the British embassy in the perestroika years and later became Ambassador to Russia, for his recollections of how things appeared at the time.

The Hoover Institution Archive staff have been unstinting in their assistance, and for this book I especially benefited from the advice I received from Lora Soroka, Carol Leadenham, David Jacobs and Linda Bernard. The staff in the Archives and Library have been a constant joy to work with. At the Reagan Library, Ray Wilson provided excellent guidance to its collections. At the National Security Archives, Tom Blanton and Svetlana Savranskaya pointed me in the direction of important documents in their collection. Richard Ramage at St Antonys has been helpful in looking out for books and articles in the Russian Library.

My thanks go to George Shultz for talking to me at length about his time at the State Department. I am also grateful to Charles Hill, Executive Assistant to Secretary Shultz in those years, for several informative conversations. Since it is part of my analysis that George Shultz along with Eduard Shevardnadze was one of the decisive enablers of the peace-making process, his oral testimony has been invaluable. I am indebted to Harry Rowen for explaining his memories and to Jack Matlock and Richard Pipes, who kindly answered queries by correspondence. On the Soviet side, I have enjoyed discussions in past years with Mikhail Gorbachvs aides Anatoli Chernyaev and Andrei Grachev, and former Deputy Foreign Affairs Minister Anatoli Adamishin has cheerfully answered queries about his diary and offered ideas about lines of research. Lord (Des) Browne, UK Defence Secretary in more recent years, and Steve Andreasan of the Nuclear Threat Initiative have sharpened my understanding on the lingering dangers of nuclear weapons in the world after the Cold War.

I have had frequent discussions at the Hoover Institution with Robert Conquest, Peter Robinson and Michael Bernstam. Each wrote influentially at the time of the events under scrutiny. I was helped by their willingness to explain the idiosyncrasies of the American political system and its dealings with the USSR. I would also like to thank Joerg Baberowski, Tim Garton Ash, Paul Gregory, Mark Harrison, Jonathan Haslam, Tom Hendriksen, David Holloway, Stephen Kotkin, Norman Naimark, Silvio Pons, Yuri Slezkine and Amir Weiner for discussions about the Cold War when we were together in the San Francisco Bay area. Hoover Institution Director John Raisians support for this and other projects has been warm and consistent over many years and the financial sponsorship of the Sarah Scaife Foundation has been much appreciated.

Conversations with Roy Giles at the Russian Centre in St Antonys College have given me invaluable insights into Western military thinking in the late 1980s. I also thank Laurien Crump for her advice on sources about the Warsaw Pact while she was a research fellow with us. I have benefited from bibliographical advice from Archie Brown, Julie Newton, Alex Pravda and Sir Adam Roberts. Richard Davy offered ideas on European security history. Over many years, Norman Daviess comments on Russia and Europe have enlivened our partnership in London and Oxford.

I have incorporated advice from colleagues who kindly agreed to read the entire final draft David Holloway, Geoffrey Hosking, Bobo Lo and Silvio Pons. I owe them a large debt for many invaluable suggestions. The same is true of Anne Deighton, Paul Gregory, Andrew Hurrell, Sir Roderic Lyne, Melvyn Leffler and Hugo Service, who examined several chapters. My literary agent David Godwin discussed the idea for the book when I returned from California excited about the material in the Hoover Archives. His encouragement is much appreciated. At Pan Macmillan, Georgina Morley has offered constant help in sculpting the book into shape. By far and away my biggest debt is to my wife Adele, who has been through the draft twice and made innumerable suggestions for improvements. I can well imagine that some of my findings will prove controversial it is unfeasible to write seriously on this subject without raising hackles. But the book has been a pleasure to research and write. The errors, misjudgements and infelicities that remain are my responsibility and mine alone.