ALSO BY TIMOTHY SNYDER

Nationalism, Marxism, and Modern Central Europe: A Biography of Kazimierz Kelles-Krauz

Wall Around the West: State Borders and Immigration Controls in the United States and Europe (ed. with Peter Andreas)

The Reconstruction of Nations: Poland, Ukraine, Lithuania, Belarus, 15691999

Sketches from a Secret War: A Polish Artists Mission to Liberate Soviet Ukraine

The Red Prince: The Secret Lives of a Habsburg Archduke

Bloodlands: Europe Between Hitler and Stalin

Thinking the Twentieth Century (with Tony Judt)

Stalin and Europe: Imitation and Domination, 19281953 (ed. with Ray Brandon)

Ukrainian History, Russian Policy, and European Futures (in Russian and Ukrainian)

The Politics of Life and Death (in Czech)

The Balkans As Europe: The Nineteenth Century (ed. with Katherine Younger, forthcoming)

Copyright 2015 by Timothy Snyder

All rights reserved.

Published in the United States by Tim Duggan Books, an imprint of the Crown Publishing Group, a division of Penguin Random House LLC, New York.

www.crownpublishing.com

Tim Duggan Books and the Crown colophon are trademarks of Penguin Random House LLC.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is on file with the Library of Congress.

ISBN9781101903452

eBook ISBN9781101903469

Maps by Beehive Mapping

Cover design by Darren Haggar

Cover art Image Source/Corbis

v4.1

a

For K. and T.

Im Kampf zwischen Dir und der Welt,

sekundiere der Welt.

In the struggle between you and the world

take the side of the world.

F RANZ K AFKA , 1917

Ten jest z ojczyzny mojej.

Jest czowiekiem.

He is from my homeland.

A human being.

A NTONI S LONIMSKI , 1943

Schwarze Milch der Frhe wir trinken sie abends

wir trinken sie mittags und morgens wir trinken sie nachts

wir trinken und trinken

The black milk of daybreak

we drink in the evening

in the afternoon in the morning in the night

we drink and we drink

P AUL C ELAN , 1944

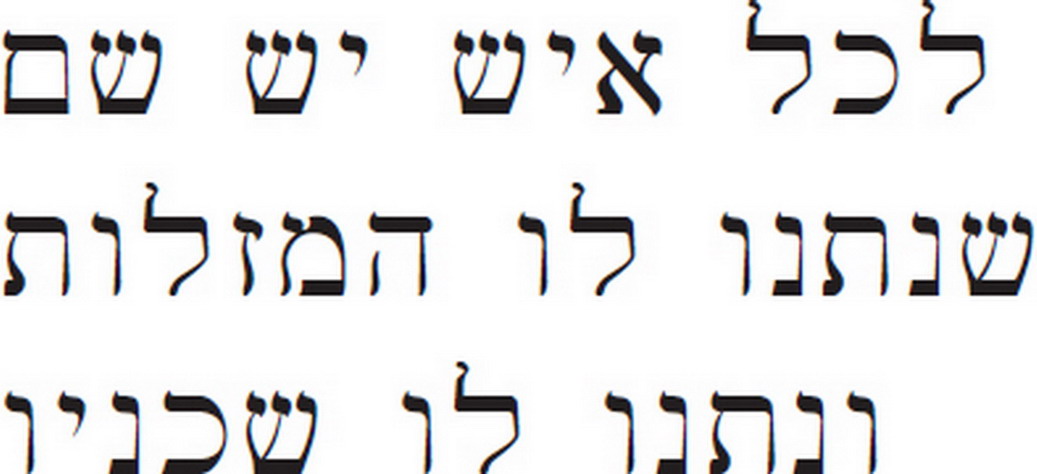

Every man has a name

given by the stars

given by his neighbors.

Z ELDA M ISHKOVSKY , 1974

Prologue

I n the fashionable sixth district of Vienna, the history of the Holocaust is in the pavement. In front of the buildings where Jews once lived and worked, ensconced in sidewalks that Jews once had to scrub with their bare hands, are small square memorials in brass bearing names, dates of deportation, and places of death.

In the mind of an adult, words and numbers connect present and past.

A childs view is different. A child starts from the things.

A little boy who lives in the sixth district observes, day by day, as a crew of workers proceeds, building by building, up the opposite side of his street. He watches them dig up the sidewalk, just as they might in order to repair a pipe or lay some cable. Waiting for his bus to kindergarten one morning, he sees the men, directly across the street now, shovel and pack the steaming black asphalt. The memorial plaques are mysterious objects in gloved hands, reflecting a bit of pale sun.

Was machen sie da, Papa? What are they doing, Daddy? The boys father is silent. He looks up the street for the bus. He hesitates, starts to answer: Sie bauen They are building He stops. This is not easy. Then the bus comes, blocking their view, opening with a wheeze of oil and air an automatic door to a normal day.

Seventy-five years earlier, in March 1938, on streets throughout Vienna, Jews were cleansing the word Austria from the pavement, unwriting a country that was ceasing to exist as Hitler and his armies arrived. Today, on those same pavements, the names of those very Jews reproach a restored Austria that, like Europe itself, remains unsure of its past.

Why were the Jews of Vienna persecuted just as Austria was removed from the map? Why were they then sent to be murdered in Belarus, a thousand kilometers away, when there was evident hatred of Jews in Austria itself? How could a people established in a city (a country, a continent) suddenly have its history come to a violent end? Why do strangers kill strangers? And why do neighbors kill neighbors?

In Vienna, as in the great cities of central and western Europe generally, Jews were a prominent part of urban life. In the lands to the north, south, and east of Vienna, in eastern Europe, Jews had lived continuously in towns and villages in large numbers for more than five centuries. And then, in less than five years, more than five million of them were murdered.

Our intuitions fail us. We rightly associate the Holocaust with Nazi ideology, but forget that many of the killers were not Nazis or even Germans. We think first of German Jews, although almost all of the Jews killed in the Holocaust lived beyond Germany. We think of concentration camps, though few of the murdered Jews ever saw one. We fault the state, though murder was possible only where state institutions were destroyed. We blame science, and so endorse an important element of Hitlers worldview. We fault nations, indulging in simplifications used by the Nazis themselves.

We recall the victims, but are apt to confuse commemoration with understanding. The memorial in the sixth district of Vienna is called Remember for the Future. Should we be confident, now that a Holocaust is behind us, that a recognizable future awaits? We share a world with the forgotten perpetrators as well as with the memorialized victims. The world is now changing, reviving fears that were familiar in Hitlers time, and to which Hitler responded. The history of the Holocaust is not over. Its precedent is eternal, and its lessons have not yet been learned.

An instructive account of the mass murder of the Jews of Europe must be planetary, because Hitlers thought was ecological, treating Jews as a wound of nature. Such a history must be colonial, since Hitler wanted wars of extermination in neighboring lands where Jews lived. It must be international, for Germans and others murdered Jews not in Germany but in other countries. It must be chronological, in that Hitlers rise to power in Germany, only one part of the story, was followed by the conquest of Austria, Czechoslovakia, and Poland, advances that reformulated the Final Solution. It must be political, in a specific sense, since the German destruction of neighboring states created zones where, especially in the occupied Soviet Union, techniques of annihilation could be invented. It must be multifocal, providing perspectives beyond those of the Nazis themselves, using sources from all groups, from Jews and non-Jews, throughout the zone of killing. This is not only a matter of justice, but of understanding. Such a reckoning must also be human, chronicling the attempt to survive as well as the attempt to murder, describing Jews as they sought to live as well as those few non-Jews who sought to help them, accepting the innate and irreducible complexity of individuals and encounters.