Cultures in Motion

PUBLICATIONS IN PARTNERSHIP WITH THE SHELBY CULLOM DAVIS CENTER AT PRINCETON UNIVERSITY

Daniel T. Rodgers, Bhavani Raman, and Helmut Reimitz, eds., Cultures in Motion

Cultures in Motion

EDITED BY

Daniel T. Rodgers, Bhavani Raman, and Helmut Reimitz

PRINCETON UNIVERSITY PRESS

Princeton and Oxford

Copyright 2014 by Princeton University Press

Published by Princeton University Press,

41 William Street, Princeton, New Jersey 08540

In the United Kingdom:

Princeton University Press, 6 Oxford Street, Woodstock,

Oxfordshire OX20 1TW

press.princeton.edu

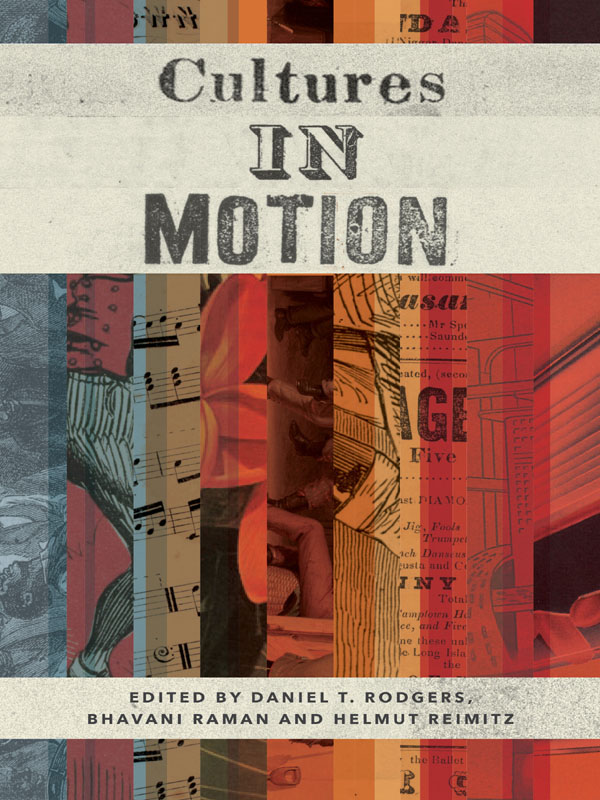

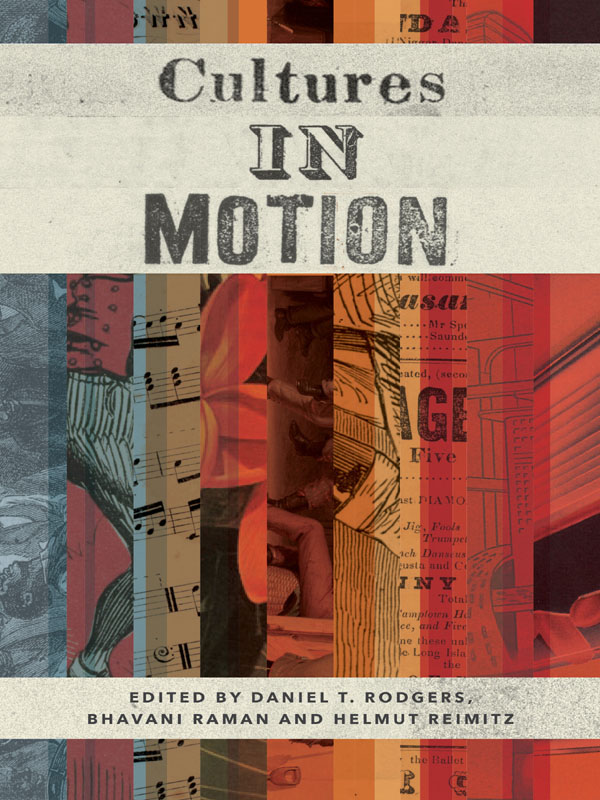

Jacket art from left to right:

Men and women dancing, from Charles Dickens American Notes, courtesy of April Masten. Specimens of theatrical cuts, courtesy of the Harvard Theatre Collection. Sheet Music, Camp Town Hornpipe, as danced by Master Diamond, courtesy of the American Antiquarian Society. Alcoa Steamship Co. ad, Holiday, April 1951, courtesy of Mimi Sheller. William Sydney Mount, Dance of the Haymakers, courtesy of The Long Island Museum of American Art, History, & Carriages; gift of Mr. and Mrs. Ward Melville, 1950. Image of Master Juba, Illustrated London News, August 5, 1848, and detail from National Theatre playbill, Boston, July 5, 1840, courtesy of the Harvard Theatre Collection. ALCOA aluminum ad, Peer into the Future, and Bohn ad, Fortune, ca. 1943, courtesy of Mimi Sheller.

All Rights Reserved

ISBN 978-0-691-15909-6

Library of Congress Control Number: 2013949385

British Library Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available

This book has been composed in Sabon LT Std

Printed on acid-free paper.

Printed in the United States of America

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Contents

Daniel T. Rodgers |

CHAPTER ONE: The Challenge Dance:

Black-Irish Exchange in Antebellum America |

April F. Masten |

CHAPTER TWO: Musical Itinerancy in a World of Nations:

Germany, Its Music, and Its Musicians |

Celia Applegate |

CHAPTER THREE: From Patriae Amator to Amator Pauperum and Back Again:

Social Imagination and Social Change in the West between Late Antiquity and the Early Middle Ages, ca. 300600 |

Peter Brown |

CHAPTER FOUR: Knowledge in Motion:

Following Itineraries of Matter in the Early Modern World |

Pamela H. Smith |

CHAPTER FIVE: Fashioning a Market:

The Singer Sewing Machine in Colonial Lanka |

Nira Wickramasinghe |

CHAPTER SIX: Speed Metal, Slow Tropics, Cold War:

Alcoa in the Caribbean |

Mimi Sheller |

CHAPTER SEVEN: The True Story of Ah Jake:

Language, Labor, and Justice in Late-Nineteenth-Century Sierra County, California |

Mae M. Ngai |

CHAPTER EIGHT: Creative Misunderstandings:

Chinese Medicine in Seventeenth-Century Europe |

Harold J. Cook |

CHAPTER NINE: Transnational Feminism:

Event, Temporality, and Performance at the 1975 International Womens Year Conference |

Jocelyn Olcott |

Bhavani Raman |

Helmut Reimitz |

Acknowledgments

THIS VOLUME GREW OUT of seminars and colloquia organized by the Shelby Cullom Davis Center for Historical Studies at Princeton University under its program from 2008 to 2010 titled Cultures and Institutions in Motion.

Since 1968 the center has undertaken the exploration of topics at the cutting edge of the historical profession. At the weekly Davis Seminar, the centers selected resident fellows join with faculty and graduate students in intensive discussion of a broad, preselected theme.

The starting points for the discussions involving the authors of this volume were the new global and transnational histories that have so profoundly reshaped historical practice in recent times. Related to the current experience of globalization but reaching back deep into the past, these inquiries have begun to map worlds in which ideas, institutions, objects, and practices were in constant motion across social and geographic space. Taken together, they challenge the premise of stable, functionally integrated cultural systems that has long been core to the historical profession. They describe worlds of trespass, boundary crossing, itinerancy, translation, and exchange that historians are just beginning to plumb.

The essays assembled here represent only a fraction of the four dozen papers presented by the centers resident fellows and others over the course of these two years. Each sparked vigorous and wide-ranging discussion of the sort for which the Davis Seminar has long been known. A full list of papers is appended. To all those who presented their work to the seminar, with a richness that we can only partially tap here, we are extremely grateful. We are grateful, too, to the seminar participantsfellows, faculty members, graduate students, discussants, and otherswho week by week tackled these issues, pressed our theme of Cultures in Motion forward, and probed its depths and complexities. Not the least we are grateful to the resident fellows, whose intellectual energy, inquisitiveness, and comradeship reverberated all through Dickinson Hall.

The Davis Centers manager, Jennifer Houle Goldman, deserves particular thanks for her efficient and gracious management of the center and the well-being of its fellows. Sarah Brooks edited the initial drafts of these essays with intelligence and care. At Princeton University Press, Peter Dougherty, director, Brigitta van Rheinberg, editor in chief, Larissa Klein, and Jenny Wolkowicki have been staunch supporters of the centers work and publishing projects.

Daniel T. Rodgers, Bhavani Raman, and Helmut Reimitz, Editors

Cultures in Motion

Cultures in Motion

AN INTRODUCTION

Daniel T. Rodgers

FOR HISTORIANS, place has been almost as foundational as gravity is to physics. A sense of bounded, stable location frames most of their professional identities and still saturates most of their work. Ask most historians what they do, and they answer geographically. They are historians of early-modern Europe, the preconquest Americas, ancient Rome, or modern Japan. Time provides the adjective; but the noun is place. The site in question may be a nation (France, Brazil), a continent (Africa), a city (London), a region (the American West), an empire (Roman, Soviet), or any of the precisely drawn and variegated locales of microhistory. But whatever the case, a sense of place as culturally set apart, with traditions, social organization, and ways of life sharply distinct from other places, still dominates most historical work.

Across those boundaries of place, external forces may intrude and disrupt, sometimes with massive consequences, but the narrative and analytical threads stay close to location. At focus is the culture of this nation, the experiences of this indigenous people, the social customs of this locale. This rooted sense of time and place distinguishes history from the social sciences that imagine that their general laws of economic or political behavior can be set down virtually anywhere with equally illuminating results.

And yet, place is not as stable or as neatly bounded as it once seemed to be. It has been almost two decades since historys sister discipline, anthropology, was overwhelmed by crisis over the match between culture and location. The axiom of Boasian anthropology, that if one got far enough from modernity one could find stable, largely homogenous culture islands, mapped neatly onto space, waiting for the ethnographic field worker to decode them, gave way to an unnerving realization that all those culture regions were, like the anthropologists own societies, porous, heterogeneous, and interconnected. They were meeting places of cultures, entrepts of goods and practices, nodes of translation and accommodation. Only the sleight of hand of the anthropologist had ever made them seem otherwise.

Next page