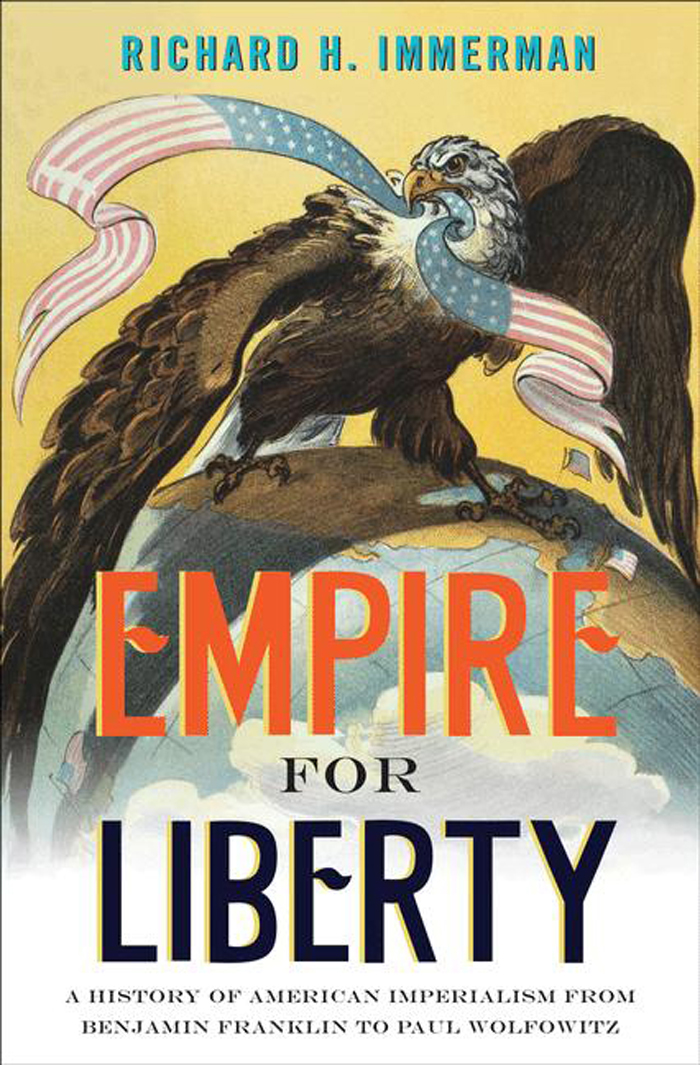

Empire for Liberty

Empire

for

Liberty

A HISTORY OF AMERICAN IMPERIALISM

from

BENJAMIN FRANKLIN

to

PAUL WOLFOWITZ

Richard H. Immerman

PRINCETON UNIVERSITY PRESS

PRINCETON AND OXFORD

Copyright 2010 by Princeton University Press

Published by Princeton University Press,

41 William Street, Princeton, New Jersey 08540

In the United Kingdom: Princeton University Press,

6 Oxford Street, Woodstock, Oxfordshire OX20 1TW

All Rights Reserved

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Immerman, Richard H.

Empire for liberty : a history of American imperialism from

Benjamin Franklin to Paul Wolfowitz / Richard H. Immerman.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-0-691-12762-0 (hardcover : acid-free paper)

1. United StatesForeign relations. 2. United StatesTerritorial expansionHistory. 3. ImperialismHistory. 4. LibertyPolitical aspectsUnited StatesHistory. I. Title.

E183.7.I46 2010

973dc22

2009040885

British Library Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available

This book has been composed in Centennial LT STD

Printed on acid-free paper.

press.princeton.edu

Printed in the United States of America

1 3 5 7 9 10 8 6 4 2

To those who educate and those who learn

CONTENTS

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

IN FUNDAMENTAL WAYS I have been writing this book since I began to study the history of U.S. foreign relations as an undergraduate at Cornell University in the late 1960s. There, in an environment defined by the Vietnam War, I along with hundreds of my fellow students gathered in Bailey Hall on Tuesday, Thursday, and Saturday mornings to listen spellbound to lectures by Walter LaFeber. It was during this time that I started to think about an American empire, and more precisely, the relationship between that empire and Americas mission of expanding the sphere of liberty. For this I owe my first thanks to Walt; to those to whom he introduced me either directly or indirectly, William Appleman Williams, Lloyd Gardner, Tom McCormick, and their colleagues; and to my peers at Cornell who were so responsible for encouraging me to think differently than I had thought before.

Over the subsequent decades, as I developed my own courses, taught my own students, and wrote my own books, the seeds of this book continued to germinate. I wont even try to acknowledge all of those who contributed to its growth. They know who they are. But I must single out two. No one has influenced how I think and write about history as much as a political scientistFred Greenstein. Not only did Fred reassure me that, notwithstanding the historiographic trajectory that accompanied that of my career, individuals do matter, but he also instructed and inspired me in ways that transformed my disposition to write about people into a scholarly undertaking. The second person I must thank specifically is at the other end of my professional spectrum: Jeffrey Engel. I did not know Jeff until he came to Temple some half-dozen years ago as a visiting fellow at the Center for the Study of Force and Diplomacy (recommended, as is only appropriate, by Walt LaFeber and Tom McCormick). But since then, particularly as I struggled with a variety of administrative responsibilities and other diversions, Jeffs energy, commitment, and relentless good cheer helped me keep my eye on the ball. Indeed, he may not remember, but it was over lunch one day with Jeff that the format of this book took shape.

Then there are my Temple students and colleagues. Few people can understand what could possibly have motivated me in 1992 to move from Hawaii to Philadelphia. For me, however, the decision was an easy one. I was coming to Temple University, where the students are not only bright but also ravenous about learning and unafraid to speak their minds. Moreover, at Temple I could collaborate with special historians like Russell Weigley and David Rosenberg to build something specialthe Center for the Study of Force and Diplomacy. I spent countless hours discussing with both the ideas that found their way into this book. When Jay Lockenour, Regina Gramer, and Vlad Zubok joined us, I immediately started to bend their ears. Then in 2004 our department went on a hiring spree that brought to Temple a remarkable group of brilliant, vibrant, and innovative young historians. For advising me, challenging me, and making me feel young again, I thank Petra Goedde, Will Hitchcock, Drew Isenberg, Todd Shepard, Bryant Simon, and Liz Varon.

I reserve two others from that group to the end. Beth Bailey and David Farber arrived at Temple in 2004 as well, but they have been my close colleagues and closer friends for decades. For that reason alone this is a better book; there are no two better historians anywhere. Further, no two scholars better appreciate the joy of writing history, and their joy is infectious.

Because of the subject matter I did a lot of the reading, writing, and thinking about this book in England. I cannot thank enough my dear friend Saki Dockrill for arranging my visiting fellowship at Kings Colleges Department of War Studies. High tea with Saki was always a true education as well an unadulterated pleasure. I must likewise thank Helen Fisher for making my stay at Kings so delightful.

At Princeton University Press I am grateful to Brigitta van Rheinberg for her invitation to turn my ideas into a book and selecting such outstanding referees (to whom, anonymous as they are, I am also grateful), to Clara Platter for her attention and management, and to both of them for their patience. Not long after my return from England, just as I began to see the light at the end of the drafts tunnel, I received an offer from Tom Fingar, the Deputy Director of National Intelligence for Analysis, to come to Washington. As Assistant Deputy Director for Analytic Integrity and Standards, my mission would be to evaluate and improve the quality of analysis across the Intelligence Community. I knew that my accepting would delay completion of the book, but I accepted nevertheless. Brigitta and Clara were wonderfully understanding. And while I wont claim that my experience in the intelligence community directly affected this book, I certainly learned a great deal about thinking more rigorously as well as critically. For that I thank Tom, my colleagues in the DDNI/A, and especially my staff in the Office of Analytic Integrity and Standards. (Im obliged to write the obvious: The views expressed in this publication are my own and do not imply endorsement of the Office of the Director of National Intelligence or any other U.S. government agency.) Richard Isomakis copyediting helped me avoid multiple hiccups in expressing my thinking.

Finally I acknowledge my wife, Marion, and daughters, Tyler and Morgan. While Ive been writing this book my entire career, none of them ever had a vote in that choice of career. That choice has led to workdays that were much longer than they bargained for, absences from home much lengthier than they liked, and from their points of view, multiple other less-than-ideal circumstances (such as denying them their Hawaiian lifestyle). Over the years Ive taken my lumps from each of them for my priorities. Yet at the same time each of them always pushed me to revise that sentence one more time, to visit one more archive, to read one more book. But at the end of the day, its simple: I thank themand love thembecause they are who they are.

Empire for Liberty