GDP

GDP

A BRIEF BUT AFFECTIONATE HISTORY

DIANE COYLE

PRINCETON UNIVERSITY PRESS

PRINCETON AND OXFORD

Copyright 2014 by Diane Coyle

Requests for permission to reproduce material from this work should be sent to

Permissions, Princeton University Press

Published by Princeton University Press, 41 William Street,

Princeton, New Jersey 08540

In the United Kingdom: Princeton University Press, 6 Oxford Street,

Woodstock, Oxfordshire OX20 1TW

press.princeton.edu

Jacket typography by Jerome Corgier/Marlena Agency. Jacket design by

Kathleen Lynch/Black Kat Design.

All Rights Reserved

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Coyle, Diane.

GDP : a brief but affectionate history / Diane Coyle.

pages cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-0-691-15679-8 (hardcover : alk. paper) 1. Gross domestic productHistory. 2. Economic history. 3. EconomicsHistory. 4. EconometricsHistory.

I. Title.

HC79.I5C725 2014

339.3109dc23

2013022478

British Library Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available

This book has been composed in Minion Pro

Printed on acid-free paper.

Printed in the United States of America

1 3 5 7 9 10 8 6 4 2

CONTENTS

GDP

Introduction

I n Greece, statistics is a combat sport. Andreas Georgiou was speaking after the announcement that he would be facing criminal charges and a parliamentary inquiry. A distinguished man who had previously spent many years working at the International Monetary Fund (IMF) in Washington, DC, Georgiou could be played by George Clooney in the movie about the European economic catastrophe. In late 2010 he became the head of Elstat, Greeces new official statistical agency, parachuted into the job by the European Union (EU) and the IMF. Within weeks his emails were being hacked, and within months he was accused by recently sacked board members of the old official statistics agency of acting against Greeces national interest. In a case that has bitterly divided opinion in Greece, prosecutors subsequently charged him with the felonies of dereliction of duty, making false statements, and falsifying official data.rescue funds to bail out the Greek government and prevent the economy from collapsing depended on the achievement of tough targets for reducing how much the government was spending and borrowing. The targets were expressed as a ratio of the budget deficit to GDPGross Domestic Product, the standard measure of the size of a countrys economy. GDP is a familiar piece of jargon that doesnt actually mean much to most people. This book is the story of how this statistic came to be so important.

According to an official European Commission inquiry published just ahead of Georgious appointment, the Greek figures had been doctored for years. The head of the National Statistical Service of Greece (NSSG, the predecessor to Elstat) had earlier that year, in some desperation, contacted European officials in Brussels, claiming official interference over the provision of figures. The inquiry concluded that there had been repeated misreporting of figures, that the Greek government could not keep track of its own spending anyway, and that there were grave doubts about the accountability of the Greek institutional frameworka bureaucratic phrase for the governments inability to control or even count its expenditure in a number of areas including defense spending.

An official inquiry was in fact unnecessary. A statistician could have told the Brussels Commissioners that the Greeks were cooking the books just by looking at the reported numbers. One potential warning signal was the announcement in 2006 that Greeces GDP was 25 percent higher than previously thought: NSSG added in an estimate of the value to the economy of off-the-books activities, hidden from the tax authorities. Greece was certainly not the only country to include in official GDP figures an estimate of the size of the so-called informal economy (as we will see later), but this large boost came at a useful time for borrowing more, as the size of GDP is key to lenders views about the borrowers capacity to repay the loan.

Apart from this change, and apart from the regular refusal by EU statisticians to approve the Greek numbers, made-up figures also have a statistical marker indicating that they have been fabricated. The pattern of GDP or other economic variables has a particular statistical fingerprint that is hard to falsify. These series of statistics are not random. Specifically, the first digit is not a 1 (or any other digit up to 9) one time in every nine, as would be the case with random statistics. Instead, the figures are far more likely to start with a 1: the first digit will be a 1 six times more often than it will be a 9, over two times more often than it will be a 3, and so on. The fingerprint pattern is known as Benfords Law. Dr. Charlie Eppes, the mathematical genius played by David Krumholtz in the crime drama Numb3rs, uses it to solve a series of burglaries in one 2006 episode, The Running Man. Greek GDP statistics did not have the Benfords Law fingerprint.

The European Commission report was clearit is some of the bluntest bureaucratic language I have ever readthat Greeces Ministry of Finance was instructing the official statisticians what the deficit and GDP figures needed to be in order to keep the loans flowing. The board of NSSG before 2010 must have either known about the fabrication or not knownin which case it was hardly an effective board for a national statistical agency. As it happens, my good friend Paola Subacchi, now director of economics at the distinguished international affairs think tank Chatham House, had visited NSSG in 2002. She flew to Athens, and took a taxi to an address that turned out to be in a residential suburb. She says: It was in a square of ordinary shops, and I had to hunt for a doorway in a 1950s apartment block that took me up some stairs to a dusty room with a handful of people. I cant remember seeing any computers. It was extraordinary, not a professional operation at all. No wonder the IMF and European Commission wanted to send in Mr. Georgiou to create a new statistical agency as a condition of lending the rescue funds to the Greek government. There might yet be nasty surprises to uncover. I am being prosecuted for not cooking the books, he said after he was accused of betraying the national interest, a crime that in theory carries a potential life sentence.

The point of this story of nefarious statistical manipulation is to highlight the importance of GDP in everyday politics and finance. In theory, Mr. Georgiou could be imprisoned for producing a different number from his predecessors. The living standards of millions of Greek peoplewould they have jobs? would they need to join the lines at the soup kitchens?depended on the figure.

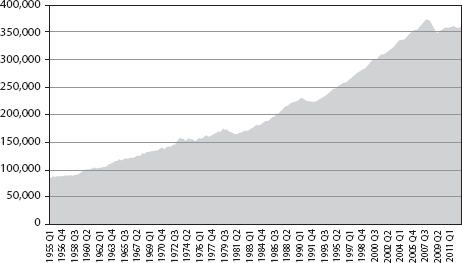

GDP is the way we measure and compare how well or badly countries are doing. But this is not a question of measuring a natural phenomenon like land mass or average temperature to varying degrees of accuracy. GDP is a made-up entity. The concept dates back only to the 1940s. As the next chapter will discuss, before then different concepts were used to measure how well the economy was doing, and even they originated only just over two hundred years ago. In the unlikely event he does ever go to prison (the inquiries are still dragging on), Mr. Georgiou will have lost his liberty over an abstraction that adds up everything from nails to toothbrushes, tractors, shoes, haircuts, management consultancy, street cleaning, yoga teaching, plates, bandages, books, and all the millions of other services and products in the economyand then adjusts them in complicated ways and for seasonal fluctuations, taking account of inflation, and standardizes them so that all countries statistics are roughly comparable, as long as they are adjusted again for some hypothetical exchange rates. You get the point: an abstract statistic derived in extremely complicated ways, yet one that has tremendous importance.

Next page