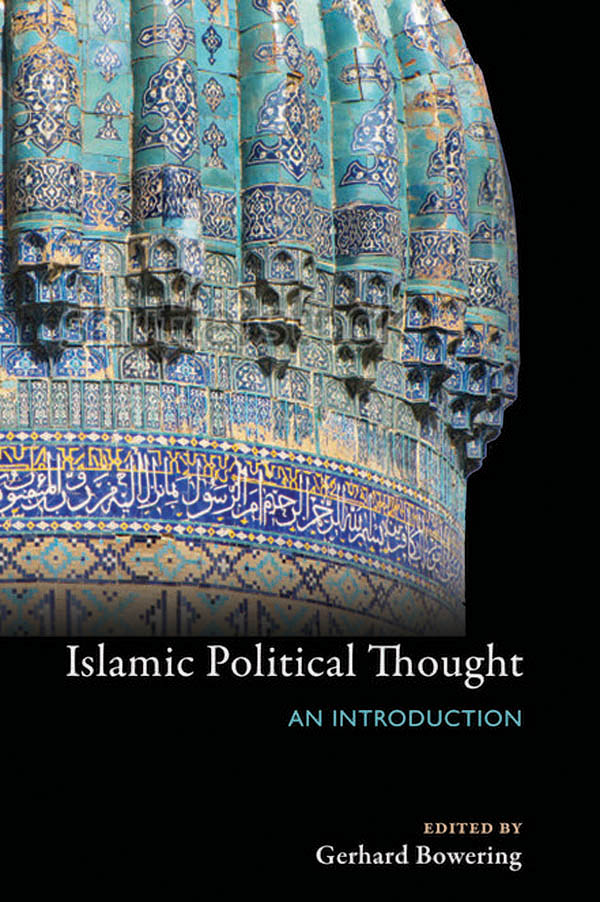

Islamic Political Thought

Islamic Political Thought

AN INTRODUCTION

Gerhard Bowering, Editor

PRINCETON UNIVERSITY PRESS

PRINCETON AND OXFORD

Copyright 2015 by Princeton University Press

Published by Princeton University Press, 41 William Street, Princeton, New Jersey 08540

In the United Kingdom: Princeton University Press, 6 Oxford Street, Woodstock, Oxfordshire OX20 1TW

press.princeton.edu

Jacket photograph Cardaf/Shutterstock.

All Rights Reserved

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Islamic political thought : an introduction / Gerhard Bowering, editor.

pages cm

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-0-691-16482-3 (pbk. : alk. paper) 1. Political scienceIslamic countries. 2. Political sciencePhilosophy. 3. Islam and state. 4. Islam and politics. I. Bwering, Gerhard, 1939

JA84.I78I85 2015

320.55'7dc23 2014023882

British Library Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available

This book has been composed in Garamond Premier Pro and Gill Sans

Printed on acid-free paper.

Printed in the United States of America

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Contents

Gerhard Bowering 1

Roy Jackson 25

Wadad Kadi and Aram A. Shahin 37

Roxanne Euben 48

Emad El-Din Shahin 68

John Kelsay 86

Paul L. Heck 105

Yohanan Friedmann 123

Armando Salvatore 135

Gerhard Bowering 152

Gudrun Krmer 169

Gerhard Bowering 185

Ebrahim Moosa and SherAli Tareen 202

Devin J. Stewart 219

Patricia Crone 238

Muhammad Qasim Zaman 252

Ayesha S. Chaudhry 263

Islamic Political Thought

Introduction

Gerhard Bowering

Islamic Political Thought: An Introduction contains 16 chapters adapted from articles in The Princeton Encyclopedia of Islamic Political Thought, a reference work published in 2013. This volume, shorter and more streamlined than the parent work, presents broad, comprehensive discussions of central themes and core concepts. These chapters were designed to integrate and contextualize the contemporary political and cultural situation of Islam while also examining in depth the historical roots of that situation.

The Islamic World in Historical Perspective

In 2014, the year 1435 of the Muslim calendar, the Islamic world was estimated to account for a population of approximately a billion and a half, representing about one-fifth of humanity. In geographical terms, Islam occupies the center of the world, stretching like a big belt across the globe from east to west. From Morocco to Mindanao, it encompasses countries of both the consumer North and the disadvantaged South. It sits at the crossroads of America, Europe, and Russia on one side and black Africa, India, and China on the other. Historically, Islam is also at a crossroads, destined to play a world role in politics and to become the most prominent world religion during the 21st century. Islam is thus not contained in any national culture; it is a universal force.

The cultural reach of Islam may be divided into five geographical blocks: West and East Africa, the Arab world (including North Africa), the Turco-Iranian lands (including Central Asia, northwestern China, the Caucasus, the Balkans, and parts of Russia), South Asia (including Pakistan, Bangladesh, and many regions in India), and Southeast Asia (Indonesia, Malaysia, Singapore, and minorities in Thailand, the Philippines, and, by extension, Australia). Particularly in the past century, Islam has created the core of a sixth block: a diaspora of small but vigorous communities living on both sides of the Atlantic, in Europe (especially in France, Germany, Great Britain, the Netherlands, and Spain), and North America (especially in Canada, the United States, and the Caribbean).

Islam has grown consistently throughout history, expanding into new neighboring territories without ever retreating (except on the margins, as in Sicily and Spain, where it was expelled by force). It began in the seventh century as a small community in Mecca and Medina in the Arabian Peninsula, led by its messenger the Prophet Muhammad (d. 632), who was eventually to unite all the Arab tribes under the banner of Islam. Within the first two centuries of its existence, Islam came into global prominence through its conquests of the Middle East, North Africa, the Iberian Peninsula, the Iranian lands, Central Asia, and the Indus valley. In the process and aftermath of these conquests, Islam inherited the legacy of the ancient Egyptian and Mesopotamian civilizations, embraced and transformed the heritage of Hellenistic philosophy and science, assimilated the subtleties of Persian statecraft, incorporated the reasoning of Jewish law and the methods of Christian theology, absorbed cultural patterns of Zoroastrian dualism and Manichean speculation, and acquired wisdom from Mahayana Buddhism and Indian philosophy and science. Its great cosmopolitan centersBaghdad, Cairo, Crdoba, Damascus, and Samarqandbecame the furnace in which the energy of these cultural traditions was converted into a new religion and polity. These major cities, as well as provincial capitals of the newly founded Islamic empire, such as Basra, Kufa, Aleppo, Qayrawan, Fez, Rayy (Tehran), Nishapur, and Sanaa merged the legacy of the Arab tribal tradition with newly incorporated cultural trends. By religious conversion, whether fervent, formal, or forced, Islam integrated heterodox and orthodox Christians of Greek, Syriac, and Latin rites, and included large numbers of Jews, Zoroastrians, Gnostics, and Manicheans. By ethnic assimilation, it absorbed a great variety of nations, whether through compacts, clientage and marriage, persuasion, threat, or through religious indifference, social climbing, and self-interest of newly conquered peoples. It embraced Aramaic-, Persian-, and Berber-speaking peoples, accommodated the disruptive incursions of Turks and the devastating invasion of Mongols into its territories, and sent out its emissaries, traders, immigrants, and colonists into the lands beyond the Indus valley, the semiarid plains south of the Sahara, and the distant shores of the Southeast Asian islands.

By transforming the world during the ascendancy of the Abbasid Empire (7501258), Islam created a splendid cosmopolitan civilization built on the Arabic language; the message of its scripture, tradition, and law (Quran, hadith, and sharia); and the wisdom and science of the cultures newly incorporated during its expansion over three continents. The practice of philosophy, medicine, and the sciences within the Islamic empire was at a level of sophistication unmatched by any other civilization; it secured pride of place in such diverse fields as architecture, philosophy, maritime navigation and trade, and commerce by land and sea, and saw the founding of the worlds first universities. Recuperating from two centuries of relative political decentralization, it coalesced about the year 1500 in three great empires, the Ottomans in the West with Istanbul as their center, the Safavids in Iran with Isfahan as their hub, and the Mughals in the Indian subcontinent with Agra and Delhi as their axis.

As the Islamic world witnessed the emergence of these three empires, European powers began to expand their influence over the world during the age of global discoveries, westward across the Atlantic into the Americas, and eastward by charting a navigational route around Africa into the Indian Ocean, there entering into fierce competition with regional powers along the long-established network of trade routes between China on the one hand and the Mediterranean and East Africa on the other. The European exploration of the East and the growing ability to exploit an existing vast trade network, together with the inadvertent but eventually lucrative discovery of the New World, were to result in Europes economic and political hegemony over the Islamic world, with which it had rubbed military and mercantile shoulders since the early Muslim conquests. The early modern Islamic world (and much of the rest of the world) fell definitively behind the West economically and politically with the advent of the Enlightenment in the 18th century and the Industrial Revolution in the 19th century.

Next page