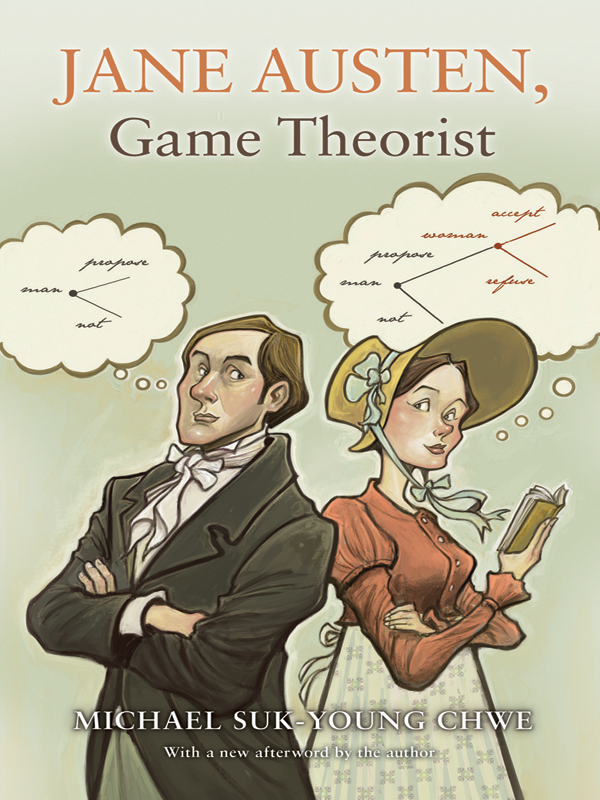

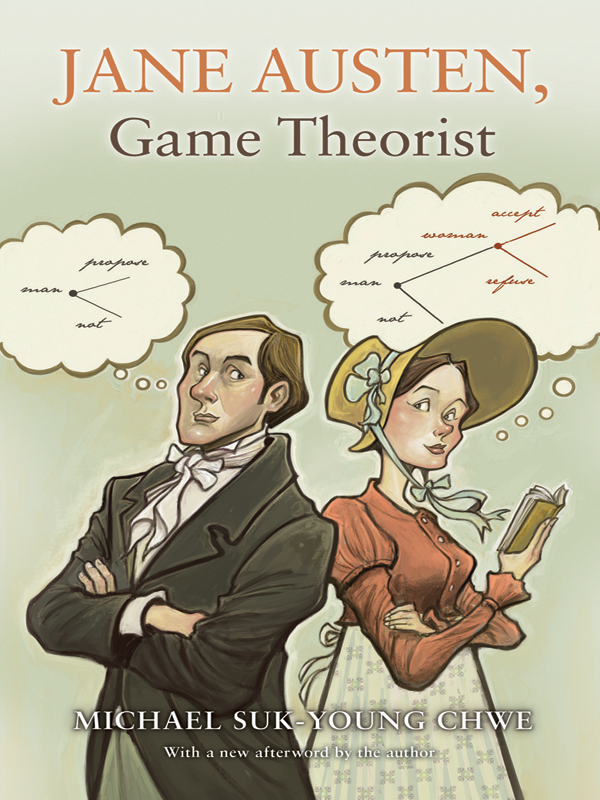

Jane Austen, Game Theorist

Jane Austen, Game Theorist

Michael Suk-Young Chwe

P RINCETON U NIVERSITY P RESS

P RINCETON AND O XFORD

Copyright 2013 by Princeton University Press

Published by Princeton University Press, 41 William Street, Princeton, New Jersey 08540

In the United Kingdom: Princeton University Press, 6 Oxford Street, Woodstock, Oxford-shire OX20 1TW

press.princeton.edu

All Rights Reserved

Fourth printing, and first paperback printing, with a new afterword by the author, 2014 paperback ISBN 978-0-691-16244-7

The Library of Congress has cataloged the cloth edition of this book as follows

Chwe, Michael Suk-Young, 1965

Jane Austen, game theorist / Michael Suk-Young Chwe. pages cm

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-0-691-15576-0 (hardcover : acid-free paper)

1. Austen, Jane, 17751817Criticism and interpretation.

2. Austen, Jane, 17751817KnowledgeSocial life and customs.

3. Game theory in literature. 4. Game theorySocial aspects. 5. Rational choice theorySocial aspects. I. Title.

PR4038.G36C49 2013 823.7dc23 | 2012041510 |

British Library Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available

This book has been composed in Sabon

Printed on acid-free paper

Typeset by S R Nova Pvt Ltd, Bangalore, India

Printed in the United States of America

10 9 8 7 6 5 4

To my sister Lana

Preface

T HE I DEA for this book started when I found Flossie and the Fox (McKissack 1986) for my children at a garage sale. For years I used the story of Flossie as an example in my graduate game theory classes but never found a place for it in my writing. The opportunity came when I was asked to prepare a paper for a conference on Rational Choice Theory and the Humanities. I found similar folktales and began to notice folk game theory in movies I watched together with my children. Watching Jane Austen adaptations led to reading her novels. Thus this book arose out of experiences with my children Hanyu and Hana. Now as they are almost grown I hope that they will still want to read books and watch movies with their father.

The Rational Choice Theory and the Humanities conference was held at Stanford University in April 2005, and I am indebted to the organizer, David Palumbo-Liu, and conference participants. Some of the material in the paper I wrote for the conference (Chwe 2009) appears again here. I am also indebted to participants in presentations I gave in December 2005 at the National Taiwan University, in April 2010 at the Juan March Institute and the UCLA Marschak Colloquium, in May 2011 at Yale University, and in June 2011 at the University of Oxford and the Stockholm School of Economics. Discussions continue at janeaustengametheorist.com.

Writing a book invariably exposes one to undeserved generosity. More than once, I have drafted what seems like a delightfully original phrase only to discover it in an email received earlier from a friend. The term folk game theory has also been independently coined in lectures by Vince Crawford and in a recent paper by Crawford, Costa-Gomes, and Iriberri (2010). Properly acknowledging the contributions of my friends and colleagues is almost impossible, but I will try. Specifically (in reverse alphabetical order), Guenter Treitel, Laura Rosenthal, Dick Rosecrance, Anne Mellor, Avinash Dixit, Vince Crawford, Tyler Cowen, Steve Brams, and Pippa Abston read the entire first draft and offered very helpful comments. Peyton Young, Giulia Sissa, Ignacio Sanchez-Cuenca, Valeria Pizzini-Gambetta, Rohit Parikh, Russ Mardon, and Neal Beck gave me great suggestions. The comments of anonymous referees improved the book, especially its overall organization, a lot. I am indebted. Chuck Myers and Peter Dougherty at Princeton University Press have always been great. Linda Truilos care as copyeditor is very much appreciated.

I wrote this book while my wife and I were both teaching at UCLA, where we landed after moving three times in search of two jobs at the same place. We are grateful to this university for its research environment and also simply for making our family life possible. I will always look back on this period of my life, with our children growing up among many loving families in Santa Monica, with the greatest affection.

Finally, I would like to thank my own family: my wife and my children, my parents, and my brothers and my sister. If I could, I would dedicate everything I do to them, not just books.

Thank you for reading, even if these words appear on some sort of device with an off switch. Real books could come into your life serendipitously, from garage sales for example. We read them. We wrote them. We loved them.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used for Jane Austens novels.

E | Emma |

MP | Mansfield Park |

NA | Northanger Abbey |

P | Persuasion |

PP | Pride and Prejudice |

SS | Sense and Sensibility |

Jane Austen, Game Theorist

CHAPTER ONE

The Argument

N OTHING IS MORE human than being curious about other humans. Why do people do what they do? The social sciences have answered this question in increasingly theoretical and specialized ways. One of the most popular and influential in the past fifty years, at least in economics and political science, has been game theory. However, in this book I argue that Jane Austen systematically explored the core ideas of game theory in her six novels, roughly two hundred years ago.

Austen is not just singularly insightful but relentlessly theoretical. Austen starts with the basic concepts of choice (a person does what she does because she chooses to) and preferences (a person chooses according to her preferences). Strategic thinking, what Austen calls penetration, is game theorys central concept: when choosing an action, a person thinks about how others will act. Austen analyzes these foundational concepts in examples too numerous and systematic to be considered incidental. Austen then considers how strategic thinking relates to other explanations of human action, such as those involving emotions, habits, rules, social factors, and ideology. Austen also carefully distinguishes strategic thinking from other concepts often confused with it, such as selfishness and economism, and even discusses the disadvantages of strategic thinking. Finally, Austen explores new applications, arguing, for example, that strategizing together in a partnership is the surest foundation for intimate relationships.

Given the breadth and ambition of her discussion, I argue that exploring strategic thinking, theoretically and not just for practical advantage, is Austens explicit intention. Austen is a theoretician of strategic thinking, in her own words, an imaginist. Austens novels do not simply provide case material for the game theorist to analyze, but are themselves an ambitious theoretical project, with insights not yet superseded by modern social science.

In her ambition, Austen is singular but not alone. For example, African American folktales celebrate the clever manipulation of others, and I argue that their strategic legacy informed the tactics of the U.S. civil rights movement. Just as folk medicine healed people long before academic medicine, folk game theory expertly analyzed strategic situations long before game theory became an academic specialty. For example, the tale of Flossie and the Fox shows how pretending to be naive can deter attackers, a theory of deterrence at least as sophisticated as those in social science today. Folk game theory contains wisdom that can be explored by social science just as traditional folk remedies are investigated by modern medicine. Game theory should thus embrace Austen, African American folktellers, and the worlds many folk game theory traditions as true scientific predecessors.

Next page