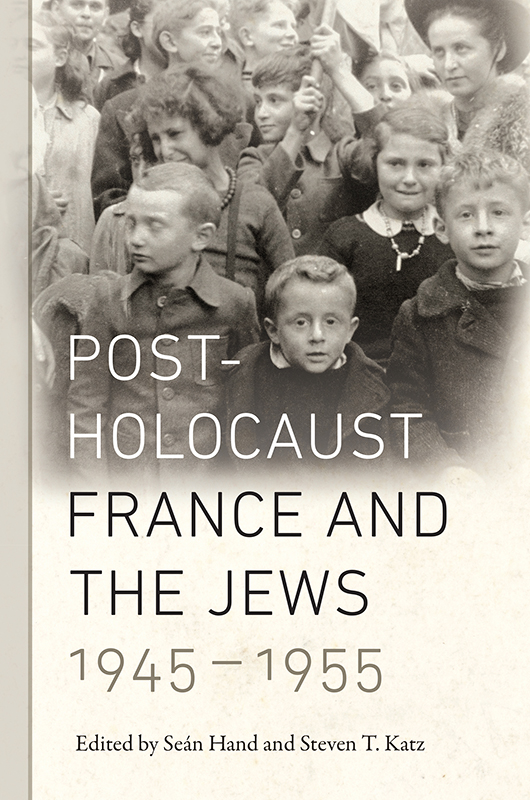

The editors wish to acknowledge the generous support of the Marilyn and Mike Grossman Conference Fund, housed at the Elie Wiesel Center for Judaic Studies at Boston University, for making possible the international conference held at Boston University in 2011 that inspired the production of this book. The editors also gratefully acknowledge the financial assistance and additional resources given to the production of this book by the Humanities Research Centre and the Department of French Studies, both at the University of Warwick. We wish to thank Dr. Claire Trvien for her translation of one chapter, and Dr. Amanda Hopkins and Holly Langstaff for their editorial assistance with all the chapters. We also thank David Lees for help with indexing. Sincere thanks, in addition, are due to Pagiel Czoka, the former Administrative Assistant at the Elie Wiesel Center, who worked tirelessly to see that everything needed for a successful conference was in place. Thanks also go to Rabbi Joseph Polak, who made the Hillel House available to us for use during the conference and provided our meals. We wish also to acknowledge the expertise, support, and friendship of Jennifer Hammer at NYU Press, and to thank the JDC Archives for permission to reproduce the cover image.

Sen Hand

This book is concerned with a pivotal moment of history in France, the first ten years of political and social reconstruction after the end of World War II. It is a period that was crucial to the restoration of a Jewish population and cultural presence in France after years of persecution and destruction, and it involved such immediate tasks as the reunification of families and communities, restitution of property and resources, and reestablishment of rescinded rights. But it is equally a decade that involved major developments that came to challenge the very notion of a restoration of order, to the extent that it changed the enshrined and understood relationship between France and Jews. For in betraying Jews in France through the implementation of anti-Semitic policies and the facilitation of murder, the Vichy state also broke the powerful pact of republican assimilation. This pact had distinguished the particular French model of Jewish emancipation sometimes called Franco-Judaism. It conferred on Jews a theoretical equality arising out of secularist and universalist principles that effectively insisted on public invisibility as a distinct grouping.been subsumed, more often than not willingly, under the powerful assimilationist ethos of the French republican model. This fundamental shift was thereafter to become further propelled by subsequent postwar events of international significance, and especially those relating to decolonization and to postCold War geopolitics, which not only altered Frances demographic makeup, including that of its identifiable Jewish population, but also tested again the historical notions of allegiance, loyalty, and cultural affiliation for Jews in France.

Yet, for all the fundamental significance of these changes in the relationship between France and Jews, this is a decade that has often been somewhat overlooked until now. The reasons for this are perhaps obvious: momentous international events take place before and after the period in question, combined with the desire in both political circles and survivors mentalities to leave behind shameful and traumatic events and focus instead on national reconstruction and hopeful emotions. Unsurprisingly, historical accounts can repeat this effect when they return to the drama and uncertainty of the wartime period. They therefore tend to focus on the treatment of Jews that for so long remained insufficiently acknowledged by official accounts, and then move forward rapidly to review such dramatic moments of change as the significant immigration of North African Jews to France caused by the Algerian war of 195462 and more generally by the regions decolonization, or to observe the tense conflict in loyalties and identifications produced by the events of the Six-Day War in 1967, including in reaction to comments made by significant figures such as Charles de Gaulle.2

To accept these large historical moments as defining, however, is also to internalize a certain timetable set in motion initially by the very synthesizing Gaullist narrrative of wartime efforts and postwar will, and therefore to overlook those fundamentally significant efforts made in many different quarters to restore the life, culture, and institutions of French Jewry in the immediate postwar period. Indeed, we could say that these movements were themselves to affect subsequent international shifts. It is therefore the aim of this volume to focus on the key relevant activities and ideas relating to the years 194555 in order to provide a fuller and truer picture of the relationship between France and the Jews on its soil at a moment of complex renovation.

At the beginning of the occupation, Jews in France numbered over 300,000. Almost two-thirds of them lived in Paris, and 190,000 were French citizens. Of the 76,000 deported from France during the war, fewer than 5 percent were to return. This does leave some 200,000 who did survive the destruction, and their numbers were to be augmented further by refugees immediately after the war, as well as at key moments thereafter. (Polls conducted in 2012 estimated the number of Jews resident in France to be between 483,000 and 600,000, making them the third-largest national grouping after citizens of Israel and the United States.) This is the size of the postwar population, then, that was to be affected by the tasks of wholesale institutional and psychological reconstruction. These tasks were undertaken by a rapidly proliferating number of committees, special operations, and purposeful individuals, whose actions and efforts took place within a period of continuing hardship and competing claims to immediate assistance. By focusing on this time, and especially by highlighting the efforts of significant Jewish organizations, large-scale related planning, and associated intellectual reconstruction, we achieve a much more continuous and informed understanding of the life, contribution, and significance of Jews in France in the postwar era. We can also note immediately that such reconstructive efforts served a difficult dual function in relation to Jewish identity. On the one hand, such identity could be naturally of a wholly practical and concrete nature, concerning, for example, the key issue of saved orphans whose psychological as well as physical welfare was forever affected by their experience. On the other hand, the question of identity effectively also had to assume the equally fundamental task of attempting to conceptualize the events that had taken place, and to propose a range of intellectual and identificatory solutions for Jewish life and culture in France and Europe. This is a task that we see enacted by such influential postwar figures as Emmanuel Levinas, Lon Poliakov, and Andr Neher. At both levels of activity, this kind of work came to assume a fundamental significance for any continuing sense of French republicanism, since these efforts effectively created a subtle shifting of weight between the coexisting dual identities of Jewish French citizen, on the one hand, and French Jew, on the other hand. This is not at all to suggest that French Jews necessarily abandoned the republican model of assimilationist identity. It is notable that postwar Jews did not relocate in significant numbers from France to Israel; and in seeking to isolate some of the reasons why this was so, we can do no better than to review the position of Ren Cassin, who provides an unambiguous reassertion of commitment to the traditional French concept of citizenship. But it remains equally true that the assimilationist model was thrown into crisis by the events of the Shoah in France, just as it has been further tested on subsequent occasions when official adherence to republican indivisibility and neutrality momentarily slipped in relation to attitudes toward Jews. In this aspect also, then, the immediate postwar period, in terms of accommodation and reaction, was effectively a foundational one for the contemporary complexities of Jewish identification and affiliation in France.3