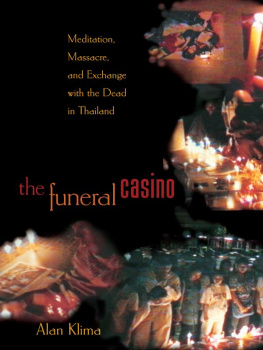

The Funeral Casino

The Funeral Casino

MEDITATION, MASSACRE, AND

EXCHANGE WITH THE DEAD

IN THAILAND

ALAN KLIMA

PRINCETON UNIVERSITY PRESS

PRINCETON AND OXFORD

Copyright 2002 by Princeton University Press

Published by Princeton University Press, 41 William Street,

Princeton, New Jersey 08540

In the United Kingdom: Princeton University Press,

3 Market Place, Woodstock, Oxfordshire OX20 1SY

All Rights Reserved

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Klima, Alan, 1964

The funeral casino : meditation, massacre, and exchange with the dead in Thailand / Alan Klima

p.cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

eISBN: 978-1-40082-496-0

1. ThailandPolitics and government19481988. 2. ThailandPolitics and government1988 3. MassacresThailand. 4. Violence in the mass mediaThailand.

5. Funeral rites and ceremoniesThailand. 6. DeathReligious aspectsBuddhism.

7. MeditationBuddhism. I. Title.

DS586 .K58 2002

959.304'4dc212001055195

This book has been composed in Sabon

British Library Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available

Printed on acid-free paper.

www.pup.princeton.edu

Printed in the United States of America

1 3 5 4 9 10 8 6 4 2

1 3 5 4 9 10 8 6 4 2

(Pbk.)

Contents

Contents

Illustrations

Illustrations

FIGURE 1

The Temple of Wealth:

The Queen Sirikit Convention Center

FIGURE 2

Painted ghetto covers

FIGURE 3

October Album (Student Federation of Thailand)

FIGURE 4

Maha Chamlong in the initial stages of hunger

FIGURE 5

Moveable feast

FIGURE 6

International correspondents occupy monumental streets cleared for sovereignty

FIGURE 7

Previewing massacre at the video market

FIGURE 8

Meditation tool

FIGURE 9

Buddhist fruit

NOTE ON TRANSCRIPTION AND MONETARY CONVERSION

In this work, some of the Thai vocabulary on technical matters of Buddhist philosophy has been exchanged for the Pali equivalents from which they are derived, for the sake of comparative use by the body of scholars familiar with these terms. At other times, as when translating speech, the Thai equivalent has been retained, but should be similar enough to be recognized as equivalent to its Pali version. For transcribing Thai words, I have used a modified version of the Haas convention, with tone and other markers dropped for the purposes of typesetting. In some cases, slight alterations have also been made for the purposes of correct pronunciation. For instance, winjaan (spirit) appears here as winyaan. For personal names and words commonly transcribed in English media, the most common form of transcription is employed. Diacritical marks are included for the Pali wherever possible within the limits of typesetting. For instance, long vowels are indicated but stops on consonants are not. Thai and Pali words are italicized only at first use.

The Thai baht is converted at the rate of twenty-five to the dollar, which was the approximate exchange rate during the times represented in this text, and during many previous years of relatively fixed exchange. In 1997 the baht was floated. At the time of writing, the exchange has stabilized for several months at approximately 45:1.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgments

My teachers are Luang Bu Sangwaan, Patcharee Katasema, Gananath Obeyesekere, John D. Kelly, Vincanne Adams, and Kaushik Ghosh. Although this book is solely my own responsibility, the impact on me of each of these peoplesome of them theorists, some Buddhists, some bothhas exemplified the fact that, given all the traces that one leaves behind, there is no other choice but to leave them with dedication and sincerity.

My aim in writing has been to explicate the parallels between various practices of visualizing death and of exchanging with the dead, but also to integrate multiple sites in ways that reflect and advocate my point of view as an author and social critic. Any other individual who would thread connections between these different sites of vision and memory in Thailand would do it differently, and Thai activists do it in their own way. This text was written, in part, by modeling its construction on Thai practices of political commemoration, and yet it is ultimately only my construction, of course, and represents quite simply an invitation to share my point of view temporarily, or not. It certainly is not an attempt to reveal an actual Thai worldview or, least of all, to tell Thais what they think. It is an expression of what I think, although also a continuation of the conversations I have had over the years in Thailand, after some time for reflection. Neither gestures to disperse ethnographic authority nor desires for the presentation of unmediated access to ethnographic subjects should distract from the fact that a critical ethnography is ultimately the argument of an author, and represents an intention to make a statement and write a historical commentary according to the vision of an author, such as it is.

I greatly appreciate everything I have learned in the discussions over the years in countless temples and villages in Thailand and in Bangkok, especially at Wat Toong Samakhi Dhamm, at Mae Moh District locations in Lampang, and in the gatherings, fortunate and unfortunate, of Bangkok. I am especially grateful to Adul Kiewboriboon and all the relatives of the dead and the injured participants in Black May who shared with me their stories, and taught me what this book had to be about. Discussions with Jarunai Dengsopha, Mali Thawinampan, Mae-Chi Liem, Mae-Chi Saad, and Mae-Chi Sangiam occupy important moments in this text, and in my life.

Writing and rewriting the book after these conversations, I have accumulated considerable debt to those who have helped me tame it. I thank John Kelly for seeing to it that I went off with a proper pair of goggles, and later for countless offhand remarks that have primed a flood of new ideas for me. I thank Vincanne Adams for the conversations, all along the way of writing, that made the puzzle of how to do this not hopeless, and perhaps possible. I thank Gananath Obeyesekere especially for his removal of a blind spot in relation to Buddhism that would have been the death of me, and for stepping in always at the right moment in my thoughts and otherwise.

I thank my reviewer Michael Taussig for his adept reading of this text, and for his generosity without receiving. I thank Rosalind Morris for the daunting bar she raised and for criticisms that I reluctantly assented to, only to discover that, although I thought she was wrong, for some strange reason my book was much better after I heeded her. And I am especially grateful for the tolerance and example of Thongchai Winichakul. It took some time of rewriting to discover how correct his comments on this text were, and these discoveries have not stopped coming even as it is finished. I have tried my best to make good on them, and yet I realize sadly, in many ways, that the events I write about call for much more than I have to give. I hope there is something between the lines of this text that bears traces of the concerns that are at the heart of writing it.

Next page

Contents

Contents