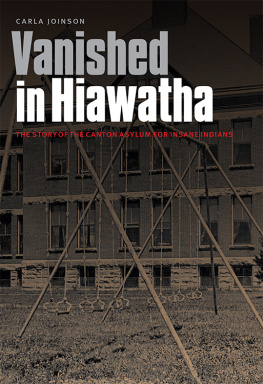

Just when we thought we had heard the worst about our treatment of Native Americans, along comes Carla Joinson with Vanished in Hiawatha. The story is painful, but Joinsons elegant narrative and prose get us through it. This powerful book is about Indiansand ourselves.

Carla Joinson exposes the notorious Canton Asylum with balance and compassion. Long overlooked, the story of this asylum has at last found a lucid, discerning, and worthy chronicler.

Carla Joinsons fine history of a harsh institution offers compelling glimpses of those forced to live there and a detailed look at the people who made it hell.

Vanished in Hiawatha

The Story of the Canton Asylum for Insane Indians

Carla Joinson

University of Nebraska Press | Lincoln & London

2016 by Carla Joinson

Cover image is from the interior

All rights reserved

Publication of this volume was assisted by the Virginia Faulkner Fund, established in memory of Virginia Faulkner, editor in chief of the University of Nebraska Press.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Joinson, Carla, author.

Title: Vanished in Hiawatha: the story of the Canton Asylum for insane Indians / Carla Joinson.

Description: Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, [2016] | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2015033012

ISBN 9780803280984 (hardback: alk. paper)

ISBN 9780803288249 (epub)

ISBN 9780803288256 (mobi)

ISBN 9780803288263 (pdf)

Subjects: LCSH : Canton Asylum for Insane Indians. Psychiatric hospitalsSouth DakotaHistory. | Indians of North AmericaMental health servicesSouth Dakota. | Indians, Treatment ofNorth America. BISAC : SOCIAL SCIENCE / Ethnic Studies / Native American Studies. | HISTORY / United States / State & Local / Midwest ( IA , IL , IN , KS , MI , MN , MO , ND , NE , OH , SD , WI ). | MEDICAL / History.

Classification: LCC RC 445. S 8 J 65 2016

DDC 362.2/109783dc23

LC record available at http://lccn.loc.gov/2015033012

The publisher does not have any control over and does not assume any responsibility for author or third-party websites or their content.

This book is dedicated to my husband, Ray. Thank you for supporting me both practically and emotionally during many long years of research, and for helping me remember that I have a life outside an archive.

Contents

Institutions filled with discontented people will always have problems. So it was at the Canton Asylum for Insane Indians. No patient wanted to be there, its employees were overworked and underpaid, and its superintendent, Dr. Harry R. Hummer, had a reputation for combining arrogance and petty self-interest with an exacting nature and an explosive temper. It had taken two decades to ratchet up the tension to near flash point, but now the bickering and accusations of mismanagement demanded that an outsider come in and see once and for all what was going on. Dr. Samuel Silk, a senior medical officer at the federal governments psychiatric hospital in Washington DC , was that outsider.

Silk expected to find some problems when he arrived at the small federal facility for insane Indians on March 20, 1929. However, he had not expected to see an epileptic girl shackled to a water pipe. He had not expected to see a ten-year-old boy in a straitjacket, in a padlocked room. Nor had he expected to see a bedridden, helpless man with a brain tumor also padlocked in a room. With growing revulsion, Silk discovered that patients were sometimes restrained for months in metal wristletsso long, in fact, that attendants occasionally lost the keys and had to saw through the links to free their captives. Urinals didnt flush, the air inside the wards reeked of excreta from overflowing chamber pots, and the corridors and rooms were dark and unforgivably squalid. In Silks words, the Canton Asylum was a place of padlocks and chamber pots. He found one elderly female attendant charged with caring for all the female patients on two stories in the main building as well as those in the separate hospital; the same overstretched situation applied to the male wards. Though that days extreme shorthandedness had been created by the abrupt departure of three employees, the situation spoke volumes. The Canton Asylum for Insane Indians had bigger problems than anyone had realized.

Nothing could be further from the stereotyped Victorian image of a madhouse than this peculiar facility, its superintendents, its patients, and most of all, its setting in the remote West of the dawning twentieth century. When I first read about the institution, I almost believed it was fictionalexcept that too many documents supported its existence. I had never considered writing anything involving the Bureau of Indian Affairs or Native Americans, but I couldnt get the asylum out of my mind. I saw immediately that something called the Silk Report held crucial information. I submitted a request for it through the state archives at the South Dakota State Historical Society and took the first step in following the threads of information that would result in this book.

Fortunately, I did not have to start entirely from scratch. Two documents (besides the Silk Report) were particularly helpful to me as I gained my bearings on this topic: the first was a graduate thesis by Kelli Sweet, and the second a doctoral dissertation by Todd Leahy. Both were informative and well researched, and they gave me an excellent overview of the asylum, its staff, its problems, and its failures.

Of course, no two researchers will come away with the same book or will focus on exactly the same points. Sweets thesis gave an informative snapshot of the asylum that included its history, patient population, and chronological high points from creation to closure. Leahy offered a broader picture of the institution as a means of social control and devoted substantial attention to the history of U.S. Indian policy and other governmental methods of coercion and control.

My own book is different from either of these works. I have not focused so much on the racism and institutionalized coercion within the Bureau of Indian Affairs as on an explanation of the asylum within the broader context of American society. I have tried to delve into why an institution like this asylum could exist for so many years, and what made it tick as a viable part of the Interior Department. I have been able to explore at least some of the patients stories, though much of their lives can be seen only through fragmented documents and a few of their own words. Above all, I have tried to capture a time and place that was as real as the broken hearts of the ill-served people who spent so many hopeless years at the Canton Asylum for Insane Indians.

When Canton Asylum came into existence, the mental health field was very much a growth industry. In 1860, just before the Civil War, How did this happen?

Mid-nineteenth-century mental health specialists with new philosophies brought hope to what had been previously considered an incurable condition. This confident new breed of doctors convinced the public that institutional care was vastly superior to home care. Though commitment often remained emotional and a last resort, families clearly found asylums a resource of great help. Increasingly, they brought their most difficult, burdensome family members to institutions, which in turn began to lose their original focus on comprehensive, personalized treatment. Far too quickly, insane asylums started to become warehouses full of long-term, chronically ill patients who had little chance of recovery. As doctors felt the pressure to admit more and more patients to relieve family distress, their institutions became overcrowded, rundown, and poorly staffed.