Contents

Guide

Pagebreaks of the print version

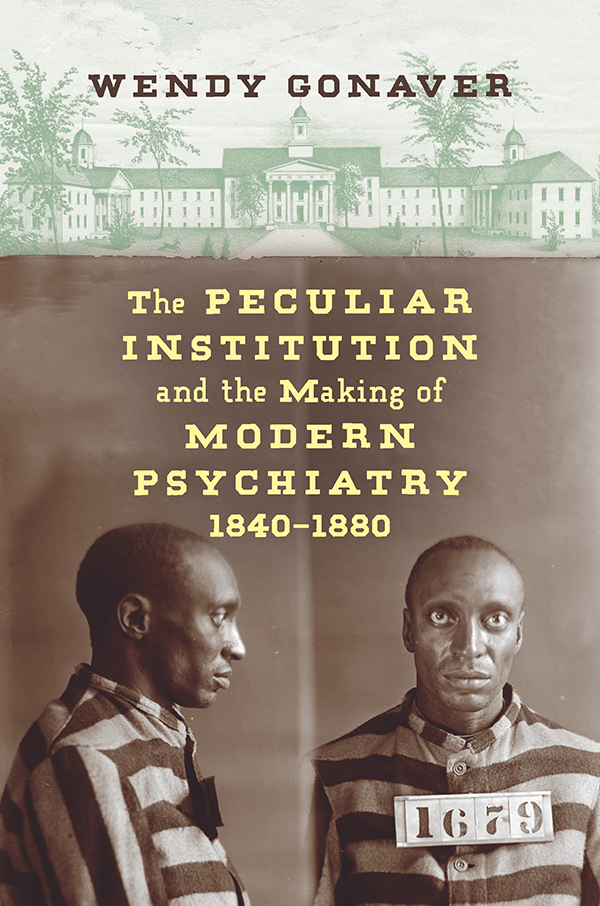

The Peculiar Institution and the Making of Modern Psychiatry, 18401880

WENDY GONAVER

The Peculiar Institution and the Making of Modern Psychiatry, 18401880

The University of North Carolina Press Chapel Hill

2018 The University of North Carolina Press

All rights reserved

Set in Arno Pro by Westchester Publishing Services

Manufactured in the United States of America

The University of North Carolina Press has been a member of the Green Press Initiative since 2003.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Gonaver, Wendy, author.

Title: The peculiar institution and the making of modern psychiatry, 18401880 / Wendy Gonaver.

Description: Chapel Hill : University of North Carolina Press, [2018] | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2018023665| ISBN 9781469648439 (cloth : alk. paper) | ISBN 9781469648446 (pbk : alk. paper) | ISBN 9781469648453 (ebook)

Subjects: LCSH : PsychiatryUnited StatesHistory. | SlaverySocial aspectsUnited States. | Social medicineUnited States. | Medical policyUnited StatesHistory. | Discrimination in medical careUnited StatesHistory. | PsychiatryPolitical aspectsUnited StatesHistory. | PsychiatrySocial aspectsUnited StatesHistory. | Psychiatric hospitalsUnited StatesHistory.

Classification: LCC RC 438 . G 66 2019 | DDC 362.20973dc23 LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2018023665

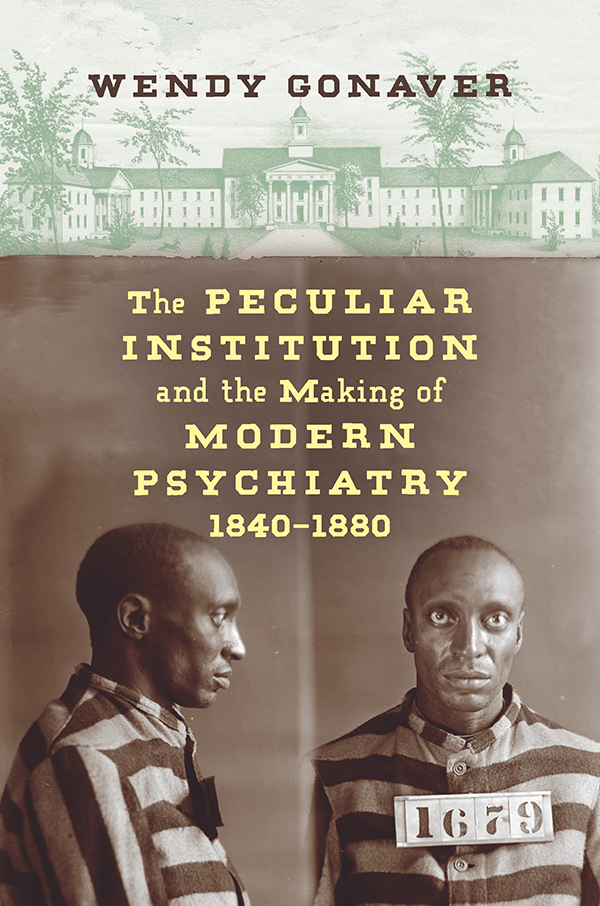

Cover illustrations: Top, photo of Eastern Lunatic Asylum by Thomas Wood, Galt Papers (II), 18401862, Special Collections Research Center, Swem Library, College of William and Mary; bottom, prisoner of Virginia State Penitentiary, Virginia Penitentiary Records, Library of Virginia.

Contents

Illustrations

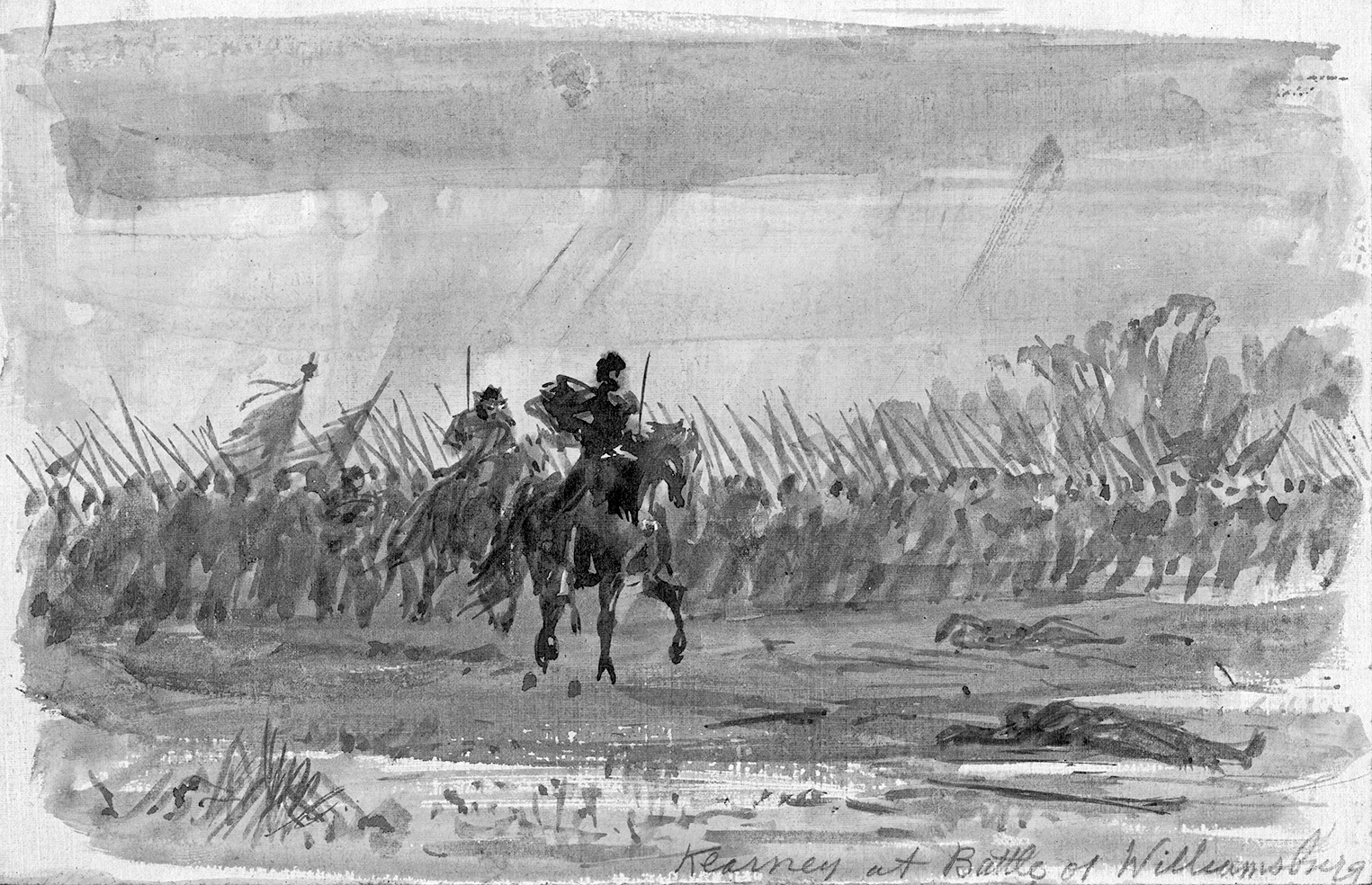

Kearney [sic] at Battle of Williamsburg

Virginia Lunatic Asylum at Williamsburg

Permission card to visit the asylum

James De Cocy, Father of White Indians

Prisoner No. 1679

Acknowledgments

I have lived with the material in this book for a long time, so Ive had ample opportunity to incur many debts. First, I thank the staff at the University of North Carolina Press for their work in turning manuscript into monograph, especially Mark Simpson-Vos, Jessica Newman, Lucas Church, and Iris Oakes. I am grateful to the three anonymous readers who were so generous with their time and insights, and to Stephen Barichko for overseeing the editing.

I cannot name every individual who offered helpful feedback at one time or another, but I must single out Melvin P. Ely for his constant support and Sharla M. Fett for her commentary at conferences. I also thank Maureen Fitzgerald, Leisa Meyer, and Scott Nelson for reading early drafts.

Several organizations provided financial support for my research, including the Consortium for the History of Science, Technology and Medicine; Virginia Center for Civil War Studies; and the Woodrow Wilson National Fellowship Foundation.

I am indebted to the librarians at Earl Gregg Swems Special Collections for their valuable assistance, especially Susan A. Riggs, Gerald Gaidmore, and Meghan Bryant. Beth Lander of the Historical Medical Library at the College of Physicians of Philadelphia and Stacey Peeples of the Pennsylvania Hospital archives were wonderfully accommodating, as were the librarians at the American Philosophical Society.

Above all, I thank the staff at Eastern State Hospital. Judy Belle Harrell and Bruce Harrell worked at the patient library for many years. It was my pleasure to work alongside them for two years, and witness their compassionate caregiving.

My deepest appreciation is for my family. I thank the late Aurora, Bob, and James A. Gonaver for providing the tools with which to build my life. I am grateful for the excellent company of some Hislers and Hufnagels. I thank David Craig, Aurora Dean, and Velia Dean for their love and hospitality. And last but not least, I thank Xiaobo Gonaver and James ONeil Spady for their love and encouragement.

The Peculiar Institution and the Making of Modern Psychiatry, 18401880

Introduction

On May 18, 1862, the superintendent of the Eastern Lunatic Asylum of Virginia, John Minson Galt II, died at age forty-two from an overdose of laudanum. It was an ignoble and unforeseeable end for a man who had begun his career full of ambitious enthusiasm, eager to make unique contributions to the fledgling field of asylum medicine. As the head of the nations oldest asylumthe only U.S. institution to accept slaves and free blacks as patients and to employ slaves as caregiversGalt had presented himself as an expert on insanity among African Americans. Over the unanimous objection of his peers, he argued against racial segregation in hospitals. In the eyes of his colleagues in the Association of Medical Superintendents of American Institutions for the Insane, of which Galt was a founding member, his racially integrated institution and use of slave labor marked him as a regressive provincial. Defiant, Galt continued to court controversy by embracing other unpopular ideas like outpatient care, for which his colleagues condemned him.

Dr. Galt was on the ideological margins of early psychiatry, but his institution was at the center of the Army of the Potomacs Peninsula Campaign of the Civil War. Williamsburg sits fifty miles east of Richmond, then the capital of the Confederacy, and thirty miles west of Hampton, where Fort Monroe, a federal garrison, was located. In the weeks prior to his death, Dr. Galt supplied the Confederate army with medicine from the asylums pharmacy and food from the kitchen. He permitted the cavalry to stable horses on the grounds, soldiers to sleep in the chapel, and evacuees from the town to hide valuables in the buildings. He had the foresight to ready a yellow flag to signal disease, but the possibility of violence at the hands of the invading Union army must have troubled him. If either army were to raid the asylums vegetable garden or claim more of the already diminished supply of pharmaceuticals, Dr. Galt knew that he would not be able to feed and medicate the almost 300 patients consigned to his care.

FIGURE 1. Kearney [sic] at Battle of Williamsburg. British-born American artist Alfred Rudolph Waud (18281891) followed the Army of the Potomac for Harpers Weekly and produced many battlefield scenes. This image of the Battle of Williamsburg on May 5, 1862, features Brigadier General Philip Kearny of the First New Jersey Brigade. LC-DIG-ppmsca-21417, Morgan Collection of Civil War Drawings, Prints and Photographs Division, Library of Congress.

Insalubrious weather aggravated these mounting anxieties. A dreary month of torrential rains had turned the countryside surrounding the hospital into pestilential bogs, increasing the risk of malaria and yellow fever. As battle grew imminent, half the residents of Williamsburg fled to the west, including asylum staff, leaving patients locked in the wards and trapped in a war zone. Finally, on May 5, the Battle of Williamsburg (see

The stress of military occupation and the inability to take his habitual two-mile walk to the landing on College Creek upset Superintendent Galts stomach. He quickly became violently ill. A euphemistically flowery obituary composed by his sister notes that Galt was sick for four days before the ailment, reflecting on the brain, caused a fatal apoplexy. In truth, Galt had been struggling for several years with a gnawing opiate dependency and a distressing sense of alienation from his professional peers. As a young man, John M. Galt had expressed reservations about slavery. He sought to avoid overt violence and permitted his enslaved staff a surprising degree of independent power. He advocated for mental health care without regard to race, the abolishment of physical restraints, and the opportunity for chronic patients to live and work with families in the community without stigma. Shunned by his fellow superintendents for his views, isolation yielded to despair once he found himself witness to the ghastly consequences of civil war. Although some of his peers publicly besmirched his reputation for having left patients vulnerable at a time of crisis by committing suicide, Dr. Galts despondency and sense of loss are understandable.