Contents

PART I

COMRADES COME RALLY

1

Party Like Its 1961

2

The Party: a Brief Biography

3

Party Man and Party Wife

4

Party Life

5

Family Party

6

Going Back to Russia

PART II

AND ILL CRY IF I WANT TO

7

Floreat Domus

8

How We Got to Be Last

PART III

MESSAGE TO THE UNBORN

9

Party Spies

10

Blind Mans Buff

11

The Referred Patient

About the Book

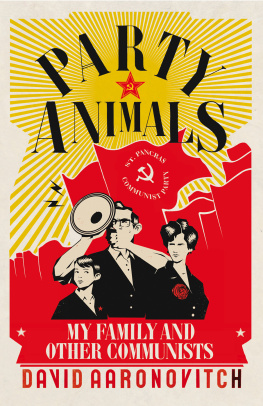

In July 1961, just before David Aaronovitchs seventh birthday, Yuri Gagarin came to London. The Russian cosmonaut was everything the Aaronovitch family wished for a popular and handsome embodiment of modern communism.

But who were they, these ever hopeful, defiant and (had they but known it) historically doomed people? Like a non-magical version of the wizards of J. K. Rowlings world, they lived secretly with and parallel to the non-communist majority, sometimes persecuted, sometimes ignored, but carrying on their own ways and traditions. Where others went to church they went to Socialist Sunday School, societys up was their down and its heroes were their villains. Who wanted American TV when you could have Russian movies?

A memoir of early life among communists, Party Animals first took David Aaronovitch back through his own memories of belief and action. But there was much more to it. He found himself studying the old secret service files, uncovering the unspoken shame and fears that provided the unconscious background to his own existence as a party animal.

Only then did he begin to understand what had come before both the obstinate heroism and the monstrous cowardice. And the elements that shape our fondest beliefs.

About the Author

David Aaronovitch is an award-winning journalist, who has worked in radio, television and newspapers in the United Kingdom since the early 1980s. He lives in Hampstead, north London, with his wife, three daughters and Kerry Blue the terrier. His first book, Paddling to Jerusalem, won the Madoc prize for travel literature in 2001 and his second, Voodoo Histories, was a Sunday Times top ten bestseller.

ALSO BY DAVID AARONOVITCH

Paddling to Jerusalem: An Aquatic Tour of Our Small Country

Voodoo Histories: The Role of the Conspiracy Theory in Shaping Modern History

For Lavender and Sam. Reunited in this, at least

Party Animals

My Family and Other Communists

DAVID AARONOVITCH

Whos going to be interested in any of it, silly boy? Its about us, its between us. It wont mean a thing to anybody else.

Leah Wesker to her son Arnold on his play Chicken Soup with Barley

PART I

COMRADES COME RALLY

1

Party Like Its 1961

Five for the years of the five-year plan

And four for the four years taken!

Red Fly the Banners O!

In the summer of 1961 the Communists of Parliament Hill Fields celebrated. Nellie Rathbone sang to herself as she picked up the milk and the Daily Worker from her doorstep in Makepeace Avenue. Old Andrew Rothsteins lips lifted the white moustache below his black homburg as he walked down Hillway on his way to the Marx Memorial Library. In the dentists surgery in St Albans Road, Rose Uren, the Party orthodontist, gripped the drill a little more lightly and may even have permitted her victims the use of an anaesthetic. Or so I imagine. I was only seven at the time, but my infant sensors could distinguish between primary emotions, and what was going on among the comrades was something close to happiness.

The cause of this good humour was the visit to Britain of the worlds first cosmonaut (which I wrongly took to be a word created by amalgamating communist and astronaut). Handsome, wholesome Yuri Gagarin was everything a British Communist wanted a Russian to be: the son of a peasant family, a proletarian apprentice in a foundry, then an officer in the Red Air Force. On 12 April 1961, Gagarin had become the first man in space. Bunched up in a tiny capsule called Vostok 1, screwed on to the end of a huge rocket, he had been blasted into the stratosphere where his smile had been picked up on grainy film and then he had been almost magically wafted to earth somewhere in the vastness of Soviet Central Asia. It was a triumph for socialism.

Three months later, on a wet and rather cold British summers day, Yuri Gagarin arrived in Manchester. It is said that small children wearing home-made cosmonaut outfits lined the terraced streets to wave to him. He appeared before crowds in Trafford Park and was noisily feted by teenage girls who weeks earlier might have been screaming for a coiffed idol with a guitar. Gagarin was sexy an attribute not often associated with Russia, with its women shot-putters and fleshy General Secretaries. In the Sunday Express the chronicler-cartoonist Giles drew a group of young women in a milk bar, swooning over a picture of the twenty-seven-year-old cosmonaut while their scowling boyfriends looked on. Good night, Elvis Presley, one was saying, good night Cliff Richard, come in Yuri Gagarin.

He came Communism came offering peace and progress, after years of isolation and Cold War. When Gagarin addressed an audience at the office of the foundry workers union he was the model of what Communists insisted Communism was all about. Although only one person was aboard the spaceship, he said, through his interpreter, it took tens of thousands of people to make it a success. Over seven thousand scientists, workers and engineers just like yourselves were decorated for contributing to the success of the flight. Major Gagarin smiled. There is plenty of room for all in outer space, he said. I visualise the great day when a Soviet spaceship landing on the moon will disembark a party of scientists, who will join British and American scientists working in observatories in a spirit of peaceful co-operation and competition rather than thinking on military lines. The crowd, apparently, stood to applaud. Peace instead of war, progress instead of backwardness, rationality instead of prejudice, planning instead of chaos.

Then Gagarin came to London. Every time a Soviet leader or hero visited they would take a big black limousine and go on a pilgrimage to the granite memorial to Karl Marx in Highgate Cemetery. There they would bow, and place flowers in front of the giant leonine head. If you stood on the dustbin by our side gate on Bromwich Avenue and peered over the fence on the afternoon of 14 July, you could see the cars slowly climbing the steep hill towards the entrance 200 yards away.

At the memorial, standing within a semicircle of local dignitaries and embassy officials, the elegant Major stood to attention and saluted the founder of Communism. And if any of the local comrades thought it was an irony that the capitalists of Britain had connived in the erection of such a large bust of the great anti-capitalist, then I never heard them say so. They lined the streets and I stood on the dustbin and we tried to discern Gagarin and then again, two years later, the first woman in space, Valentina Tereshkova, followed by Alexei Leonov, the first man to walk in space, and Popovich, whom we named a puppy after, as they looked out of the windows of their black cars the socialist future come at last to pay tribute to the prophetic past.