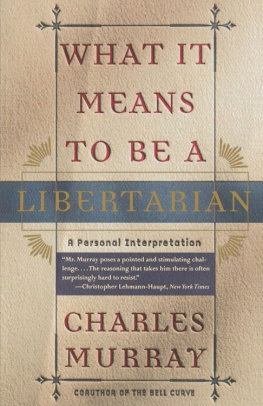

PRAISE FOR

W HAT I T M EANS TO B E A L IBERTARIAN

Seldom has so much substance and wisdom been packed into so few words. You might think that such a sweeping agenda would require a huge book. But, in fact, the political justifications for these huge governmental activities are remarkably vulnerable, as Murray demonstrates by puncturing them with a few well-placed thrusts.Forbes

[An] important new book by Charles Murray, one of Americas most controversial and important social scientists, will be added to the must-read list of those who want to understand more about the ideas that are coming to dominate the thinking of governments around the world.Chicago Tribune

It is a useful book; to echo Charles Handy, it should be compulsory reading for all politicians.Economist

[Murray] is persuasive when [he] identifies in the nations hallowed traditions as well as present-day sensibilities a prominent libertarian core. The prospects for the heralded renaissance can only be enhanced by the appearance of [this] intelligent, readable volume.National Review

[What It Means to Be a Libertarian] is a provocative, lean manifesto. For the polemic, the bare-bones argument, read Murray. For anyone of an age or an ambition to look into the likely political debates, causes and shifts of government in the first quarter of the twenty-first century, I recommend [it].Baltimore Sun

Speaking of broader appeal, Murray does not venture back into the murky waters of IQ analysis in this current volume. He sticks to the time-honored ideas he inherits from other libertarians and explains them with clarity and charm.New York Press

Murray, in this book, aims to be a Tom Paine for our times. Even a committed nonbeliever can appreciate an author who sets forth his normative ideas and proposals in such arresting terms.Washington Post Book World

A LSO BY C HARLES M URRAY

Losing Ground: American Social Policy 19501980

In Pursuit: Of Happiness and Good Government

The Bell Curve: Intelligence and Class Structure in American Life

(with Richard J. Herrnstein)

To the memory of my friends Richard Herrnstein and Karl Hass,

as different as two men could be except in their courage,

kindness, and wisdom.

C ONTENTS

Let us, then, with courage and confidence pursue our own federal and republican principles, our attachment to our union and representative government. Entertaining a due sense of our equal right to the use of our own faculties, to the acquisitions of our industry, to honor and confidence from our fellow citizens, resulting not from birth but from our actions and their sense of them; enlightened by a benign religion, professed, indeed, and practiced in various forms, yet all of them including honesty, truth, temperance, gratitude, and the love of man; acknowledging and adoring an overruling Providence, which by all its dispensations proves that it delights in the happiness of man here and his greater happiness hereafter; with all these blessings, what more is necessary to make us a happy and prosperous people? Still one thing more, fellow citizensa wise and frugal government, which shall restrain men from injuring one another, which shall leave them otherwise free to regulate their own pursuits of industry and improvement, and shall not take from the mouth of labor the bread it has earned. This is the sum of good government, and this is necessary to close the circle of our felicities.

T HOMAS J EFFERSON

First Inaugural Address

March 4, 1801

I NTRODUCTION

I N THE LAST QUARTER of the eighteenth century the American Founders created a society based on the belief that human happiness is intimately connected with personal freedom and responsibility. The twin pillars of the system they created were limits on the power of the central government and protection of individual rights.

A few people, of whom I am one, think that the Founders insights are as true today as they were two centuries ago. We believe that human happiness requires freedom and that freedom requires limited government. Limited government means a very small one, shorn of almost all of the apparatus we have come to take for granted during the last sixty years.

Most people are baffled by such views. Dont we realize that this is postindustrial America, not Jeffersons agrarian society? Dont we realize that without big government millions of the elderly would be destitute, corporations would destroy the environment, and employers would be free once more to exploit their workers? Where do we suppose blacks would be if it werent for the government? Women? Havent we noticed that America has huge social problems that arent going to be dealt with unless the government does something about them?

This book tries to explain how we can believe that the less government, the better. Why a society run on the principles of limited government would advance human happiness. How such a society would lead to greater individual fulfillment, more vital communities, a richer culture. Why such a society would contain fewer poor people, fewer neglected children, fewer criminals. How such a society would not abandon the less fortunate but would care for them better than does the society we have now.

Many books address the historical, economic, sociological, philosophical, and constitutional issues raised in these pages. A bibliographic essay at the end of the book points you to some of the basic sources, but the book you are about to read contains no footnotes. It has no tables and but a single graph. My purpose is not to provide proofs but to explain a way of looking at the world.

A Note About the Way This Book Uses the Word Libertarian

The correct word for my view of the world is liberal. Liberal is the simplest anglicization of the Latin liber, and freedom is what classical liberalism is all about. The writers of the nineteenth century who expounded on this view were called liberals. In Continental Europe they still are. In the pages that follow, I will occasionally use the phrase classical liberal to remind readers of this tradition. But words mean what people think they mean, and in the United States the unmodified term liberal now refers to the politics of an expansive government and the welfare state.

The contemporary alternative is libertarian. The problem here is that many of the leading thinkers of the libertarian movementLibertarians with a capital l, if you willpresent a logic of individual liberty that is purer and more uncompromising than the one you will find here. The similarities are great, but I am only a lower-case libertarian. I am too fond of tradition and the nonrational aspects of the human spirit to be otherwise. I am also conscious, however, that libertarians of the stricter school, fighting a lonely battle for many years, have established equity in the word. Many will understandably be annoyed at my applying the label to views that owe so much to another lowercase libertarian, Adam Smith, as well as to a conservative hero, Edmund Burke.

But it is also true that I have considerable company. A growing wing of libertarian thought has been working to reconcile the imperatives of human freedom with the indispensable roles that tradition and the classical virtues play in civic life. In an etymologically perfect world these people would still be called liberals, but they call themselves libertarians without fretting about it. From now on I will, too.