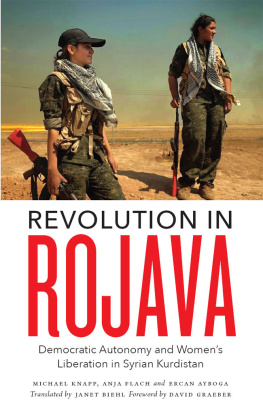

Revolution in Rojava

Revolution in

Rojava

Democratic Autonomy and Womens

Liberation in Syrian Kurdistan

Michael Knapp, Anja Flach,

and Ercan Ayboa

Foreword by David Graeber

Afterword by Asya Abdullah

Translated by Janet Biehl

First published 2016 by Pluto Press

345 Archway Road, London N6 5AA

www.plutobooks.com

Copyright Michael Knapp, Anja Flach and Ercan Ayboa 2016

The right of Michael Knapp, Anja Flach and Ercan Ayboa to be identified as the authors of this work has been asserted by them in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

ISBN 978 0 7453 3664 0 Hardback

ISBN 978 0 7453 3659 6 Paperback

ISBN 978 1 7837 1987 7 PDF eBook

ISBN 978 1 7837 1989 1 Kindle eBook

ISBN 978 1 7837 1988 4 EPUB eBook

This book is printed on paper suitable for recycling and made from fully managed and sustained forest sources. Logging, pulping and manufacturing processes are expected to conform to the environmental standards of the country of origin.

Typeset by Stanford DTP Services, Northampton, England

Simultaneously printed in the United Kingdom and United States of America

Contents

List of Figures

Translators Note

Revolution in Rojava, the first full book to appear on the democratic, gender-equal, cooperative revolution under way in northern Syria, was originally published in German in March 2015 by VSA Verlag. This English version began as a direct translation, but over the course of 16 months, it has been extensively revised and updated, so that in many respects it is a new book. I would like to thank Pluto Press for editorial support and for bringing the book to the wide audience it deserves; Sherko Geylani, for early help with translation; and New Compass Press for solidarity.

Janet Biehl

Foreword

David Graeber

Even many ostensible revolutionaries nowadays seem to have secretly abandoned the idea that a revolution is actually possible.

Here I am using revolution in its classical sense, lets say: the overthrow of an existing structure of power and the ruling class it supports by a popular uprising of some sort, and its replacement by new forms of bottom-up popular organization. For most of the twentieth century this was not the case: even those revolutionaries who hated the Bolsheviks, for example, supported the revolution itself, even popular uprisings that came to be led by ethno-nationalists were not simply condemned if they were seen to be genuinely popular. There was an obvious reason for this. For most of that time, revolutionaries felt that, whatever temporary complications, history was flowing inevitably in the direction of greater equality and freedom. Those rising up to shake off some form of tyranny, however temporarily confused or distracted, were clearly the agents of that greater movement of liberation.

Its understandable that its hard to maintain that kind of blind optimism anymore. It often led to extraordinarily destructive naivet. But neither is it particularly helpful to replace naivet with cynicism, and it must be admitted that in many quarters, this is what has happened. A very large portion of those who at least think of themselves as the revolutionary left now seem to have adopted a politics which leads to the instant and near automatic condemnation of pretty much any even moderately successful revolutionary movement that actually takes place on planet earth. Certainly this is what has happened in the case of Rojava. While a large number of people have been utterly astounded, and deeply moved, to see a popular movement dedicated to direct democracy, cooperative economics, and a deep commitment to ecology emerge in that part of the world theyd long been informed was the very most authoritarian and benighted, let alone to witness thousands of armed feminists literally defeating the forces of patriarchy on the battlefield, many either refused to believe any of this was actually happening, or tried to come up with any reason they could for why there must be something deeply insidious lying behind it. One expects this kind of reaction from the mainstream media, or US and European politicians. After lecturing the world for generations about how the peoples of the Middle East were desperately backwards, and how their traditional and supposedly uncompromising hostility towards liberal values like formal democracy and womens rights justified both the support of extreme right-wing regimes like Saudi Arabia (what else can you expect from people like that?) and endless bombing and massacres against the population unfortunate enough to live under whichever regimes the Empires guns happened to be trained on, its hardly surprising that the emergence of popular movements embracing forms of democracy far more radical, and not just womens rights but genuine full womens equality, in all aspects of life, would be a topic theyd prefer to avoid. But the left?

These reactions I should stress went well beyond mere skepticism, which of course is healthy (indeed necessary): I have former friends, English activists who had never taken a strong interest in Middle Eastern affairs, who on learning of the Rojava Revolution decided the appropriate response was to appear at any event about the region in London to distribute pamphlets condemning the revolution and urging people not to help it. What on earth would move someone to conclude that, of all the things they could be doing to further the cause of universal freedom and equality in the limited days they had left upon this planet, this would be the best usage of their time?

* * *

In my unkinder moments, I am tempted to label such elements the Loser Leftby which I mean, not that they are personally inadequate in any way, but that they have embraced a politics which tacitly assumes the inevitability of ultimate defeat. Admittedly, this attitude has always been with us. Consider the phrase fighting the good fightit seems to carry within it an assumption that of course one will not win. But since the end of the Cold War the Loser Left has ballooned enormously. I would suggest that, as currently constituted, it has two main divisions: purists, and extreme anti-imperialists. The first have taken the old Marxist vanguardist idea that anyone who doesnt adopt every detail of my particular form of doctrine isnt really a revolutionary, and pushed it just a step further to conclude that any revolution that doesnt fit my theory of what a real revolution should look like is worse than no revolution at all. In anarchist and some Marxist circles, this attitude converges around a kind of cool-kid clubbism: many, one suspects, are unconsciously horrified at the prospect of a revolution, since that would mean everyone, even hairdressers and postal workers, would be debating Thorie Communiste or Aufheben and there would be nothing special about them anymore.

The anti-imperialists are a stranger case. I am not obviously speaking here of anyone who opposes the global dominance of North Atlantic military powers: its hard to imagine how one could be a revolutionary and not do so. Financialized capitalism is essentially military capitalism; the power of JP Morgan Chase or even Standard & Poors is entirely dependent on the power of the US military; even the inner workings of capitalist profit extraction increasingly work through simple coercive force. These things are not extricable. What I am speaking of here instead is the feeling that foiling imperial designsor avoiding any appearance of even appearing to be on the same side as an imperialist in any contextshould always take priority over anything else. This attitude only makes sense if youve secretly decided that real revolutions are impossible. Because surely, if one actually felt that a genuine popular revolution was occurring, say, in the city of Koban and that its success could be a beacon and example to the world, one would not also hold that it is better for all those revolutionaries to be massacred by genocidal fascists than for a bunch of rich white intellectuals to sully the purity of their reputations by suggesting that US imperial forces already conducting airstrikes in the region might wish to direct their attention to the fascists tanks. Yet, astoundingly, this was the position that a very large number of self-professed radicals actually did take.