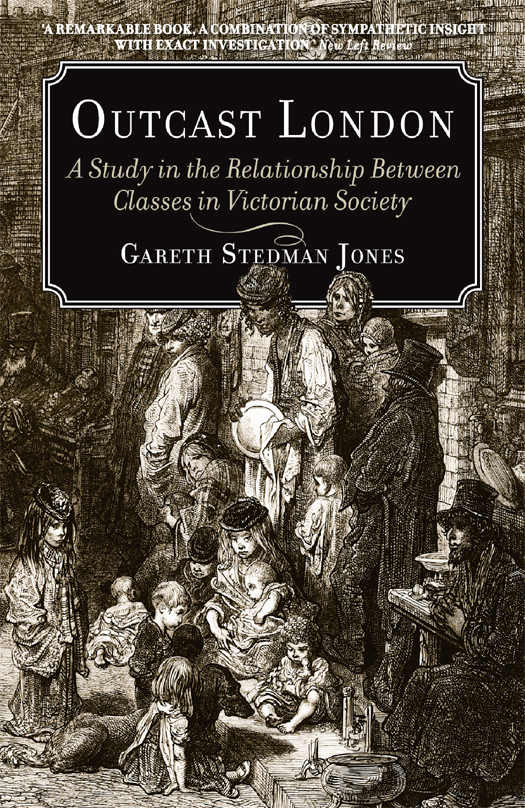

Gareth Stedman Jones is a Fellow of Kings College, and Director of the Centre for History and Economics, University of Cambridge. In 2010 he became Professor of the History of Ideas at Queen Mary, University of London. He is the author of An End to Poverty? and Languages of Class: Studies in Working-Class History 18321982.

This edition first published by Verso 2013

First published by Oxford University Press 1971

Published by Penguin Books 1976, 1984

Gareth Stedman Jones 1971, 1976, 1984, 2013

Work in London images 15, Living in the Slums images 1, 4, and 6, and Unrest images 1 and 2 courtesy of Bishopsgate Institute, London.

All rights reserved

The moral rights of the authors have been asserted

Verso

UK: 6 Meard Street, London W1F 0EG

US: 20 Jay Street, Suite 1010, Brooklyn, NY 11201

www.versobooks.com

Verso is the imprint of New Left Books

ISBN (US): 9781781680551

ISBN (UK): 9781781686270

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

A catalog record for this book is available from the Library of Congress.

v3.1

CONTENTS

LIST OF PLATES

WORK IN LONDON

1. Progress of the London Victoria Docks

2. Taking on Hands at the London Docks

3. The Victorian Rush Hour The Arrival of the Workers Penny Train at Victoria Station

4. Anger at the Victorian Sweatshop The Horrors of the Cheap Clothing Trade

5. Help for the Unemployed? The Victorian Stoneyard

LIVING IN THE SLUMS

1. Tenement Dwellings in the 1880s

2. An East-End Slum

3. Moving House, December 1894

4. The Street Trades Collecting Rag and Bone, c. 1890

5. Slumland Childrens Games

6. A Slum Interior in the 1890s

UNREST

1. The Riots at the West End, 1886

2. The Great Dock Strike of 1889

3. The Great Dock Strike of 1889 Parade of Coal Heavers on Strike

4. John Burns Addresses the Men during the Great Dock Strike of 1889

5. A Political Demonstration, 1896

LIST OF TABLES, MAPS, AND FIGURES

PREFACE TO THE 2013 EDITION

As a contribution to the writing of history, Outcast London was very much a product of the 1960s: or more precisely, the decade following 1965. Those were years in which impatience with received traditions of method and interpretation was accompanied by the search for new and more experimental forms of historical understanding. A preceding generation of radical historians, which included Christopher Hill, Rodney Hilton, Edward Thompson and Eric Hobsbawm, had explored indigenous sources of radicalism, from the Peasants Revolt to the emergence of the labour movement, whether in the form of agrarian resistance, history from below radical dissent, or labour history. Nearly all this work had been conceived within a Marxist paradigm which went back to the 1930s and the Popular Front.

Among a new generation beginning to write in the mid-1960s, an adventurous political and intellectual radicalism was developing. It aimed not only to broaden the scope of history, but also to question the form and content of its inherited narratives. Feminism challenged the conventional approach to labour and radical history; interest in extra-European movements in the Third World broke free from the polarities of the Cold War and the confinement of national cultures. The new social movements of the 1960s and 1970s were increasingly transnational, both in their scope and in their concerns.

Some of us also had a growing sense of the parochialism of English culture. This was accompanied by a desire to look beyond what then seemed the complacent verities of a common-sense Anglo-Saxon empiricism and explore alternative philosophical traditions, located particularly in Western Europe or the Third World. This new form of intellectual radicalism found expression in work on psychoanalysis, in the development of structuralism, in innovative kinds of film studies and in the New Left Review s construction of Western Marxism as an alternative canon of Marxist but non-communist thought.

Outcast London articulated the new intellectual and political interests of the 1960s in a number of ways. As the book reveals, I was particularly inspired by French work in history and social theory. What sort of future newly decolonised nations might enjoy, and whether they could escape the economic effects of imperialism, were at the time still open questions, even sources of hope. It was my reading about the economics of under-development and the problems of urban poverty that later inspired me to investigate parallel problems in nineteenth-century London.

Once embarked upon graduate research, I was able to put my interest in the economics and culture of poverty to use. For historians in search of conceptual innovation, social anthropology was then an area of particular intellectual excitement. Keith Thomas had shown in 1963 how anthropology might illuminate the understanding of witchcraft. With the help of Mauss, I was able to move questions about charity away from worthy but uncritical histories of philanthropy, and present them instead as crucial areas of social anxiety in the relationship between the wealthy and the outcast.

Althusser had not only developed this critique of historicism, but also produced alternative concepts that could be applied to the history of ideas. What strikes me now about this usage of the term problmatique is how far it had already moved away from conventional ideas about ideology, and how close it already was in certain respects to the later idea of discourse.

This discussion of the intellectual sources of Outcast London could easily be enlarged, but they are described in more detail elsewhere. for me to attempt to evaluate as a whole. I will, therefore, do no more than mention a few of the works that have touched most closely upon themes I had explored. In light of this work, themes of Outcast London have been broadened, modified or sometimes entirely transformed.

Most striking has been the development of research on gender and sexuality in Victorian and Edwardian London, a dimension that barely existed in the 1960s. On the role of women in the casual economy, see the pioneering work of Ellen Ross, Love and Toil: Motherhood in Outcast London 18701918 (1993), also Duncan Bythell, The Sweated Trades: Outwork in Nineteenth-Century Britain (1978); more generally on women and work see Sally Alexander, Becoming a Woman: and Other Essays in 19th and 20th Century Feminist History (1994). On prostitution and sexuality, an area rarely discussed in the 1960s beyond the salacious snippets found in My Secret Life , there is now a formidable body of serious research including Franoise Barret-Ducrocq, Love in the Time of Victoria: Sexuality and Desire among Working-Class Men and Women in Nineteenth-Century London (1992), and Judith Walkowitz, City of Dreadful Delight: Narratives of Sexual Danger in Late-Victorian London (1992). Particularly striking has been the new research agenda into philanthropy and slumming. In addition to the standard enquiry of Standish Meacham, Toynbee Hall and Social Reform 18801914: The Search for Community