Contents

Guide

The author and publisher have provided this e-book to you for your personal use only. You may not make this e-book publicly available in any way. Copyright infringement is against the law. If you believe the copy of this e-book you are reading infringes on the authors copyright, please notify the publisher at: us.macmillanusa.com/piracy.

Visiting Buenos Aires in March 2001, it was hard not to see the approaching economic catastrophe.

Closed signs hung on many shop doors; taxi drivers carried on and on about the dire straits of the country in terms that were dramatic, even allowing for the Argentine penchant for embellishment; the cover of the leading newsmagazine featured a picture of the controversial finance minister wearing a Hannibal Lecter mask, referencing the horror movie The Silence of the Lambs , and the question Did he have to cannibalize the country to save it?

I had just come from the annual meeting of the Inter-American Development Bank in neighboring Chile, where bankers, ministers, and journalists furrowed their brows over Argentinas financial problems, the Chileans no doubt feeling somewhat smug given their long-standing national rivalry with Argentina.

If youd seen the numbersforeign debt rising, dollars leaving the country, reserves plummeting, expensive restructurings that padded bankers pockets but didnt do much to help Argentina dig out of its holeyou had to know that there was no way Argentina could keep up. With its peso pegged to the dollar, it couldnt easily devalue the currency to jump-start the economy. Investors were selling Argentine bonds en masse; prices had fallen to what in retrospect was a still generous eighty cents on the dollar. But you didnt have to see the numbers to come to this conclusion.

As a financial journalist specializing in Latin America, a few weeks later I wrote about a proposal, floated by a group of respected academics and Wall Streeters, for Argentina and its creditors to reduce its debt by 30 percent in order to avoid a bigger, chaotic haircut later. After I published the article, several Wall Street bankers called me to say that this was what needed to happen, but they couldnt say so in public or theyd be fired. Even though traders spoke about Argentinas pending default as a matter of when rather than if, no bank dared tell its shareholders that it would be the first to voluntarily part with a single penny of what it was owed. Nine months later, the worst came true. Argentinas currency collapsed, and the banks that didnt want to give up 30 percent ended up losing roughly 70 percent of their money.

Fast-forward a decade to Greece. Like Argentina, Greece was trying to paper over its debt problem with a series of bailouts that only postponed the day of reckoning. Other European economies, though not so bad off as Greece, were struggling as well. In spring 2011, I published a paper for the New America Foundation arguing that Greece needed to learn from Argentinas failure to recognize and respond to a highly probable financial catastrophe by restructuring its debt soonerbefore it was too late.

The reaction to the Greek problem was very different from the reaction to what happened in 2001: this time investors spoke openly, in public, about what needed to happen in Greecethat is, what Argentina should have done in 2001. It came down to the wire, but early in 2012 Greeces government and its private-sector creditors came to an agreement that kept the country from defaulting on its private debt and bringing Europe and the global economy down with it. The countrys government creditors were a different story, which would bring Greece and all of Europe to a new crisis in 2015.

In 2011, the organizers of the Global HR Forum, a Korean organization focused on human-resources challenges, asked me to attend their November conference in Seoul and speak about whether the world faced a new economic crisis. Well, I told them, we hadnt yet climbed out of the one we were in. We were still dealing with the same mess wed been in for the past few years. It wasnt just Greece; huge fiscal and trade imbalances in other countries across Europe also threatened to pull the euro apart and drag the global economy along with it. To American eyes, European leaders seemed to be doing no more than muddling through the crisis. They were not making the politically difficult choices that could get them out of trouble. So I spoke about the choices between kicking the can down the road and making tough decisions on some of the biggest issues facing the global economy: growth and austerity, short and long term, fiscal and monetary policy, consumption and investment, cheap labor and human capital, producing goods or knowledge.

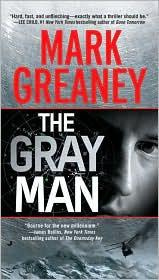

When the Greek private-sector deal came through a few months later, the contrast between the story lines of Argentina and Greece got me wondering: What made the difference? How were Greece and its private-sector creditors able to make the proverbial stitch in time that prevented a catastrophe for its own economy and threatened to bring down the rest of Europe with it? Those are the questions that planted the seed for writing The Gray Rhino. They also would come into play again for Greece, because, despite the breathing room the country won when it cut a deal with banks and hedge funds, it still owed a lot more to the International Monetary Fund and the European Union. These official creditors, funded by national governments, ultimately depended on taxpayersparticularly German oneswho balked at doing what the private creditors had done.

Since the release of Nassim Nicholas Talebs The Black Swan: The Impact of the Highly Improbable and its extraordinary timing just ahead of the 2008 financial crisis, many people in financial markets and policy circles have obsessed over Black Swan or Fat Tail crisesthat is, events that individually may be highly improbable but which as a group occur far more often than most people realize. Yet those analysts and planners didnt have a similar way to focus their energies on things that were dangerous, obvious, and highly probable. To me, it seemed that behind many Black Swans was a converging set of highly likely crises.

As I began to look for examples of Gray Rhinos, it became clear that so many of the big crises of the past had started as highly obvious but ignored threats, and that the biggest challenges today are also obvious but ignored. I began seeing evidence everywhere of clear dangers that were recognized but werent being addressed, from climate change and financial crisis at the global-policy level to disruptive technologies that reshaped entire industries (as digital technologies did to media, destroying jobs and companies but creating new multibillion-dollar fortunes for founders of new firms) and highly personal problems that may not qualify as high-impact on a global scale but certainly had a profound effect on the individuals facing them. There were so many times when we should have done better at responding to obvious threats: Hurricane Katrina, the 2008 financial crisis, the 2007 Minnesota bridge collapse, cyber attacks, wildfires, water shortages, and other disasters that youll read about in this book.

As Hurricane Sandy roared up the East Coast in October 2012, I reflected on the storm-warning systems that gave New York several days to prepare. In the aftermath of the storm, it became clear that although emergency-response officials had learned some lessons from the governments disastrous handling of Katrina, there were many examples of people, companies, organizations, and government agencies that had not prepared for the storm. And after Sandy it wasnt at all clear whether the people who had the power to make necessary changes to protect New York in the future would do so.