This is a work of creative nonfiction. The events are portrayed to the best of the authors memory. While all the stories in this book are true, some names and identifying details have been changed to protect the privacy of the people involved.

Published by Greenleaf Book Group Press

Austin, Texas

www.gbgpress.com

Copyright 2016 Edward M. Warner

All rights reserved.

No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without written permission from the copyright holder.

Distributed by Greenleaf Book Group

For ordering information or special discounts for bulk purchases, please contact Greenleaf Book Group at PO Box 91869, Austin, TX 78709, 512.891.6100.

Design and composition by Greenleaf Book Group

Cover design by Greenleaf Book Group

Cover image provided by Lowveld Rhino Trust

Cataloging-in-Publication data is available.

Print ISBN: 978-1-62634-227-9

eBook ISBN: 978-1-62634-228-6

Part of the Tree Neutral program, which offsets the number of trees consumed in the production and printing of this book by taking proactive steps, such as planting trees in direct proportion to the number of trees used: www.treeneutral.com

Printed in the United States of America on acid-free paper

15 16 17 18 19 20 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

First Edition

Contents

Acknowledgments

BEFORE YOU GET TO A single story, I must do what authors feel a desperate need to do and readers find boring as heck: acknowledge all those people without whom this book would never have been written. It goes without saying the wonderful, sometimes ridiculous characters you are about to meet made these stories possible.

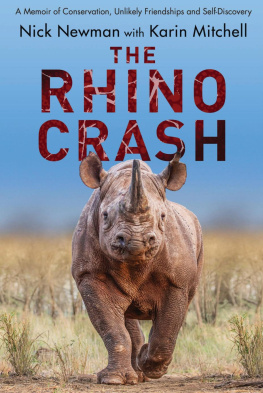

I tip my hat to Raoul du Toit and Natasha Anderson, who run the Conservancy Project for the International Rhino Foundation. Its difficult to find words to express my admiration for their dedication to saving these magnificent animals. The black rhino cow and calf that beautifully run across the cover were donated by the Lowveld Rhino Trust, one of the funding agencies helping protect rhinos in southeastern Zimbabwe.

I would never have found my way to conservation in Africa if it werent for Karl Hess, Jr., founder of The Land Center and now retired from the US Fish and Wildlife Service, and Brent Haglund, president of the Sand County Foundation. I still work with Brent and Mike Jones, my good friend and partner in Resilience Science projects.

Id also like to thank all those scientists from academia and the nonprofit world who endlessly supplied me with professional reading when in 2000 I decided to switch careers from geology to community-based natural resource management (CBNRM)and working with private landowners on wildlife stewardship. Thanks to you, the first three years of my new life were not wasted on fables, falsehoods, and faithinstead, they fostered the best re-education I could have received.

Thank you, Brandy Savarese, for editing the manuscript, and thanks to the whole Greenleaf team. I expected editing to be like a root canal, but in fact you made the process of editing and publishing enjoyable.

To Jackie, my wife and life partner in adventures, thank you for saying, Go. Just go. Get outta here and go to Africa. Without your support I would have still gone to Africa but it was a lot more fun going together.

The rhino cow and calf featured on the Table of Contents page is from a sketch Jackie drew on the envelope of one of my birthday cards. This book is dedicated to you, darlin.

Introduction

AS THE SUN SANK IN the west, the sky turned the color of faded jeans. We had paused for lunch on the banks of Zimbabwes Chiredzi River when the shortwave radio squawked to life. Up in the Husky, a little two-seat, single-engine airplane, Raoul was receiving an update on the location of the badly injured baby black rhino the scouts had been looking for all afternoon. Members of our crewthey had been napping under a treerushed to gather their gear and climb into their respective helicopters, a Eurocopter owned by Paul Tudor Jones and a Robinson 44 owned and flown by John McTaggart. Blake (Blake was an owner of the now-defunct Chiredzi River Conservancy. No one at Rhino Ops could remember his real name!) fired up his Land Cruiser as the helicopter rotors whined into action, and we all took off in a cloud of dust. Accompanying me in the Cruisers open back were two game scouts, Blakes ten-year-old son Peter, and the developmentally disabled, thirteen-year-old daughter of a visiting Canadian veterinarian. We hung on to the roll bar for dear life.

Blake careened down a rough dirt track, then bounced through a newly plowed maize field. I can remember thinking, Keep your jaw shut or youll chip your teeth, and tossing away the fried chicken leg that would have otherwise constituted the days lunch. At the end of the field, we picked up a game trail leading into the woods. As we headed down and around a blind turn, we were halted by a tree almost certainly pushed down by an ill-mannered elephant. Without wasting a second, the game scouts attacked the roadblock with their razor-sharp, two-foot long, machete-like pangas.

Within two minutes and a spray of wood chips flying in all directions, the track was cleared and we lurched onward into a sand wash that nearly caused us to flip over. I had taken the moment we started up to wipe my greasy and sweaty palms on my bush shorts, already filthy with rhino blood and dust, but I managed to grab hold of the roll bar again before I pitched head-over-cab into the creek bed.

Ten minutes later we found ourselves up against an impenetrable wall of acacia thorn bush. There was no way to get the Land Cruiser any closer to the field site.

So we jumped out and ranusing the helicopter noise to vector into the location of the injured baby rhino.

Running with Rhinos is not a euphemismnot when youre the ground support for World Wildlife Funds Rhino Conservancy Project, specializing in the preservation of black rhinos.

There are two species of rhinoceroses in Africa. The white rhino, or square-lipped rhino, is a social, grazing animal. There are approximately twenty thousand, many on private game ranches in the Republic of South Africa. The white rhino is the second largest land mammal, with bulls reaching upward of 6,000 pounds. While they are dangerous to approach, they are docile compared to their cousins, the black rhinos.

The black rhinos prehensile hooked lip enables it to eat leaves and twigs of bushy plants, rather than graze. It prefers the semiarid habitat of the thorn-bush Lowveld, the savanna land of forest, grassland, and thorn-bush scrub. While it is smaller in stature than the white rhino, weighing in at a mere 3,000 pounds, it is far more dangerous. The black rhino is solitary unless with a calf. Fewer than five thousand black rhinos remain in the wilds of sub-Saharan Africa, with the largest populations in South Africa, Namibia, and Zimbabwe. About five hundred, or more than 10 percent, live on private lands in Zimbabwe.

So, another book about rhinos? Hasnt enough been written by professional wildlife biologists and amateur environmentalists?

Well, yes and yes. But theyre not stories written by a long-term, non-professional volunteerhimself a scientistwho has worked for more than a decade with the veterinarians and biologists who care for rhinos in Africa. Few if any laymen like me have been invited to do what amounts to some of the most dangerous volunteer fieldwork around.