ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

W ildlife and wilderness may be the subject of this book, but its true genesis lies in the people who inspired it. I met many of them when I first traveled through the great wildlife parks of Rhodesianow Zimbabwethirty years ago. They were of a breed Id never encountered before. They were fiercely independent and self-sufficient, their minds sharp and intelligent, but their creed was simple: wilderness and wildlife are priceless, and theres a job to be done, so lets get on with it. Any difficulties along the way were met with an equally simple proposition: well make a plan.

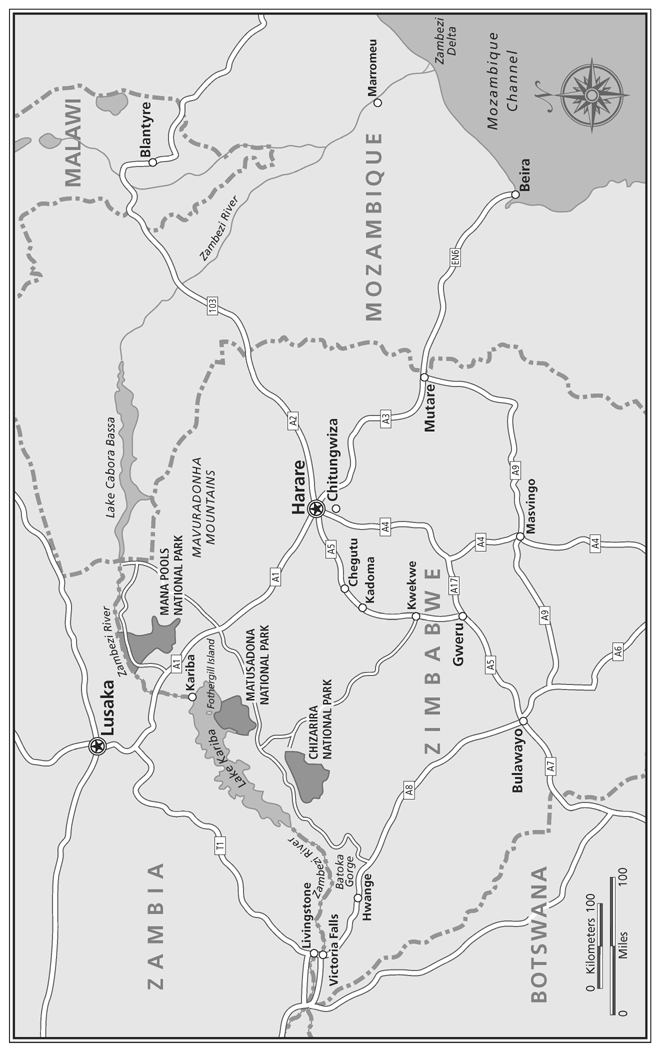

Some of these peopleRob and Paddy Francis in the Gonarezhou, Nick Tredger in Chizarira, Ronnie van Heerden, John Stevensare mentioned in these pages. And special mention must go to the people in Mana Pools and the Matusadona, who inspired my love for these very special places. In Mana Pools, Dolf Sasseen cut through all the complexities with a single phraseIts all so beautiful.

In Matusadona, Rob and Sandy Fynn, who built their dream on Fothergill Island, shared it with me for almost two years and so gave me the freedom to think, absorb, and begin to understand my own most profound enigmamyself.

Kevin and Fay Dunham and Russell Taylor put some of the complexities back by showing me the biological truths that underlie the Zambezi Valleys fragile beauty. They may feel they wasted their time when they see how Ive dealt with some controversial wildlife issues, but they possess two importantand sometimes rarescientific traits: a lack of dogmatism, and a sense of humour.

There were many others, and if I tried to list them, Id be in grave danger of giving offence by omission. But, to all those who gave so freely of their hospitality, knowledge, and friendship to a would-be writer all those years ago (and, by example, diverted him into wildlife conservation for the next quarter-century), I have to say: thank you.

Then, years laterwhen the make-a-plan breed was in danger of dying outMike Cock and Mark Atkinson saved what was left of Zimbabwes fast-disappearing black rhinos with a magnificent disregard for bureaucratic obstruction. Andy Searle, persecuted in other contexts by the same bureaucrats, lived and died in pursuit of his ideals.

And the flame still burnsin Loki Osborne and Richard Hoare, for instance, who are dedicated to the survival of Africas elephants.

In the late Zeph Mukatiwa, a recent Matusadona wardenand in Duncan Purchase, now director of the Zambezi Society, who bore many of my administrative burdens while I was writing this book. If I have misquoted them, I apologise; but I like to think that I have preserved the general tenor of their inspiring lives, actions, and words. They led me to make my own planto write this book.

But putting the plan into effect is, it goes without saying, the most important part of the tradition. This was deceptively easyuntil I sent the resulting manuscript to Jennifer Barclay at Summersdale Publishers. Thats when the hard work really began.

Jennifer gave me constant encouragement through three drafts in as many years, gently but firmly pointing out my literary sins, from the superfluous and pretentious to the misplaced apostrophe.

I was naturally delighted when Jennifer told me that Lyons Press had agreed to publish an American editionand, I have to say, more than a little apprehensive. Would I have to do yet another redraft? But it seems not. Ellen Urban and Lilly Golden have overseen the books American incarnation with unfailing encouragement and few requirements for additional input on my part.

Remarkably, this has all been accomplished by e-mail, overat my enda slow and temperamental Zimbabwean dialup connection. If they were frustrated by my delayed and erratic responses, they never showed it.

But this means Ive never met Jennifer, Ellen, or the many others at Summersdale and Lyons Press who have been so helpful. I hope to put this right before too long, because Ive come to think of them as friends.

Lee Durrell is a very special person, who deserves an equally special mention. I sent her an early manuscript, on the strength of a brief but deeply inspiring acquaintance with herself and Gerald almost twenty years ago. That Leewho has walked with literary giantsshould agree to write the foreword is, I think, more of a tribute to her generosity of spirit than to my own talents.

And that brings me, above all, to Sal, my friend, bush-companion, colleague, fellow writer, and wife. Those who can read between the lines of this book will gather that I spent many years in an emotional wilderness, as well as a literal one, before Sal came into my life. Without Sal, nothing would have been written at all because it wouldnt have been worth the effort. Nor would anything else in life.

WALKING IN STRANGE WAYS

T heres a flash and a loud bang somewhere behind our house as the illicit panel-beating business down the road fires up its welding machine. The lights go out and my computer dies, along with a thousand unsaved words of immortal prose.

Bugger it, I hear Sal say in the kitchen as she is plunged into darkness, not again. The pasta, which had been simmering nicely, subsides into a glutinous mass inside its saucepan.

The telephone is working for once, but it takes me an hour to get through to the Zimbabwean Electricity Supply Authority (ZESA), possibly because half of Harare is trying to do the same thing. When I finally do so...

Your fault number, a pleasant voice says, in a Shona accent, is five-seven-nine-four-five. My fault? Nicely worded, guys. Shifts the blame squarely onto my shoulders.

And when can you attend to it? I ask, with studied courtesy. Theres a long silence.

Aaaah, the voice finally says. We dont have fuel.

It being my fault, I suppose Im responsible for giving them the fuel to come out and fix it. I grab a can from my little stockpile of diesel, drive to the ZESA depot, watch the cheerful, blue-overalled truck driver pouring it into his tank, and go home before I can watch him siphoning half of it out again.

The electricitythe ZESA, as everyone calls it herecomes back on at two in the morning, and sets the burglar alarm off. Its siren wails and shrieks through the house, and starts the dogs howling in chorus. A car screeches to a halt in the road outside and three sinister-looking men in black with big boots come leaping over the wall. I go out to meet them and am instantly transfixed by a blinding spotlight.

Stand steel and put your hands up! a voice yells at me. What is your cod number?

We havent got any cod, but there are a couple of goldfish in the pond right beside you, why dont you ask them? Im not sure why this sort of smart-arse retort should come to mind when someones pointing a pistol at me. Theyre not the sort of last words Id want to be remembered for.

FIVE, SEVEN, I bellow, um... er... Theres a slight but menacing movement of the spotlight, and the click of a safety catch.

Thats the ZESA fault number, idiot, Sal mutters, materialising beside me. Code number two-five-four-one, guys, she says sweetly, turning to the spotlight. It goes out.

Ah, Madam, it is you, the biggest and most intimidating man says, with the relieved air of a man whos finally found someone who talks sense. Your husband must learn the cod number. Otherwise we might shoot him.

Dont bother, Ill do it myself one of these days, Sal says. The dogs are still howling away. Shut up, Crash, quiet, Ember. And for Gods sakes, love,she addresses me, without any detectable change in tone, turn that bloody siren off.

I give the security guys a handsome tip for their troubleits not often you pay someone to stick a gun in your ear in your own front gardenand let them out, noting that similar scenes are being played out up and down the road.