ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying and recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, except as may be expressly permitted in writing from the publisher. Requests for permission should be addressed to Globe Pequot Press, Attn: Rights and Permissions Department, P.O. Box 480, Guilford, CT 06437.

Lyons Press is an imprint of Globe Pequot Press.

Text designer: Sheryl P. Kober

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available on file.

Let a person walk alone with few wishes, committing no wrong, like an elephant in the forest.

The greatness of a nation and its moral progress can be judged by the way its animals are treated.

I WAS CROUCHED IN A SMALL CLEARING IN THE DENSE AFRICAN BUSH with the trackers about 10 meters (11 yards) ahead of me when all hell broke loose. The trackers had unexpectedly come across not one but three lionesses, and they had cubs. Contrary to what many people think, the first instinct of a wild animal is to run from humans. However, a lioness with cubs will stand her ground and not hesitate to attack if she feels threatened. The females facing us felt very threatened indeed. Their snarls and growls reverberated in my chest, and to put it mildly, I was terrified. The prospect of being mauled to death loomed large. Once again it crossed my mind that I should be sitting on the patio at my home in Cape Town, sipping a drink, and gazing at the calm sea. How did I wind up in the bush facing death?

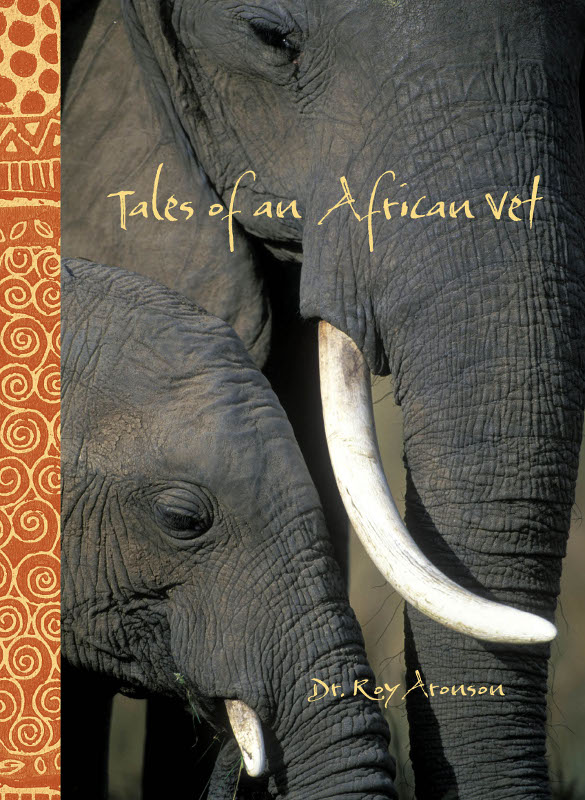

My name is Roy Aronson. I am a South African veterinarian. I graduated from veterinary school in 1984 and have been in private practice ever since. In that time I have had many exciting and sometimes treacherous experiences.

I have tracked lions and cheetahs, anesthetized rhinos, collared elephants, and nearly lost a foot to a hungry crocodile. Ive shot a bull running amok, come face-to-face with an angry hybrid wolf, been spat at by a cobra, and attacked by a puff adder. I have seen the devastating effects of poaching, and Ive had to make some tough decisions about the fate of an animals life time and time again.

When I think back, I realize that there were pivotal moments when my life intersected with that of an animals, and I was forever changed. These moments have shaped my life. The animals Ive helped are indelibly etched on my consciousness. The vets that I have had the privilege of working with have become personal friends. I am immeasurably richer for having met them.

In the following pages, I will introduce you to many characters who populate my story. You will meet the Huchzermeyers, both father and son, who are vets; Peter Rogers, a dedicated wildlife vet and one of the great ones; and Professor Dave Meltzer, a world-renowned expert on cheetah breeding. You will also meet Jabu the elephant, Munwane the rhino, Savannah the cheetah, and Mehlwane the lionesssome of the many animals I have had the amazing privilege of helping.

Many of the stories in this book came from experiences I had while filming episodes for a proposed TV show about being an African vet. Although the TV series has yet to make the screen, the lessons I learned from these people, animals, and experiences have made me a better person and a better vet. I hope that when you read these stories, some of the wisdom that has rubbed off on me will rub off on you too. Theres a saying that goes like this: Measure the risk and the reward; make sure the reward is worth the risk.

I have taken risks when working with wild and potentially dangerous animals, but the reward has been a life filled with treasured memories. Sometimes the risks my colleagues and I take can have effects so far reaching that not even in our wildest dreams could we have foretold the reward. How lucky we are to work in a profession that offers so much joy. I hope you will enjoy these stories as much as Ive enjoyed being a part of them.

WHEN WERE YOUNG, ENTHUSIASTIC, AND PASSIONATE, SOMETIMES WE do crazy things. I have always been a determined person, and once I get the bit between my teeth, I dont like to give up. A few years before I entered veterinary school, I was serving in the South African navy. I was just twenty years old and a bit reckless then, attempting to do things that an older and wiser person may not have. I was fairly happy at the thought of how my future looked just then. My actions, however, set me on a path that I would otherwise not have trod.

I graduated from the University of Cape Town in 1975 with my first degree, a bachelor of science with majors in microbiology and biochemistry, and successfully applied to join the navy. I was based in Simons Town, a picturesque fishing village on the stormy False Bay coast in the Western Cape about 20 miles from Cape Town itself. I was assigned to a laboratory that did quality control work in the engineering field. I was given various tasks to do, but I was also allowed to choose one or two special interest projects to keep me occupied if I had any spare time. I chose to do some investigations into antifouling paints that are used to coat ships to prevent barnacles from attaching to the hulls. If not for them, literally tons of barnacles would add massive drag to the ships. This would, of course, slow them down and dramatically increase fuel consumption. Not a good idea for a naval warship.

My project involved coating small pieces of steel with the various antifouling paints available, hanging these pieces of steel at various depths from a raft moored in the bay at Simons Town, then measuring the number of barnacles that attached themselves. In this way I was able to assess the effectiveness of the paints and compare them so that the navy could choose the best one. I am sometimes pedantic, and the attention to detail needed in this sort of work has a certain charm to me, while it might appear tedious to others.

I was given the use of a small rowboat to access a raft moored on one side of the harbor, out of the way of passing vessels. My raft was moored next to a number of floating pontoons where seals would sun themselves. I diligently set up my experiment and hung numerous plates from ropes going down into the blue depths of the Simons Town harbor. My experiment was designed to run for a year, through all four seasons.

I spent many happy hours rowing out to my little raft in the harbor and measuring the number of barnacles that had attached themselves to my plates that were coated with a substance designed to prevent just that. It never ceased to fascinate me how those clean, painted plates attracted and accumulated life in abundance. First the plate became slightly roughened as microscopic sea creatures attached themselves to it. Then over a period of a few days, the rough patches started to take the form of miniature barnacles that you could see with the naked eye. These grew until eventually after nearly a year they had become sea creatures coated in a hard shell. During the summer months, Id row out with my shirt off, and when it was really hot, Id dive into the water in my shorts and spend some time in the sun drying off before I rowed back to the shore and my lab. Clearly, this was a busy time for me. I was hard at work and having a good time. In the winter, though, it was a lot less fun. False Bay has one of the largest populations of great white sharks in the world. I kept an eye out for cruising toothy monsters that could easily reach 6 meters (20 feet) in length.